Jataka 25

Tittha Jātaka

The Horse at the Ford

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

There is a subtle point to make in stories like this one. Some schools of Buddhism say that only a guru can “impart transcendent knowledge.” But you will not find this in the Buddha’s teachings. Even a Buddha is only a guide. You must make the journey. A wise teacher can help create the conditions for awakening, but only the dedicated student can attain awakening by his or her own effort and skill. A teacher is like a coach; a student is like the athlete.

There is, however, an error in this story. It says that only a Buddha can know the hearts and minds of others. While I would not say it is common, the ability to read minds is known even among non-Buddhists. This was probably added to make the Buddha seem even more remarkable.

“Change the spot.” This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana. It is about an ex-goldsmith who had become a monk and was living as a companion with the Guardian of the Faith (Sāriputta).

Now, only a Buddha knows the hearts and minds of others. Because he lacked this power, the Guardian of the Faith told his companion to use impurity as the theme for his meditation. This was not an appropriate them for meditation for that monk. The reason why it was no good to him was that, according to tradition, he had been born for 500 consecutive births as a goldsmith. The cumulative effect of seeing absolutely pure gold for so long had made the theme of impurity useless. He spent four months without making the slightest progress in his meditation. Finding himself unable to help his companion, the Guardian of the Faith thought to himself, “This must be someone that only a Buddha can teach. I will take him to the Buddha.” So at early dawn he took the monk to the Master.

The Master said, “What has brought you, Sāriputta, here with this monk?”

“Sir, I gave him a theme for meditation, and after four months he has not made even the slightest progress. So I brought him to you thinking that he is someone that only a Buddha can teach.”

“What meditation, Sāriputta, did you prescribe for him?”

“The meditation on impurity, Blessed One.”

“Sāriputta, you do not have the power to know the hearts and minds of others. Leave us and come back in the evening to get your companion.”

After the Elder left, the Master had the monk change into a nice under-cloth and a robe. He kept him at his side when he went into town for alms, and he made sure that he received the best food. That evening, as he walked around the monastery with that monk by his side, he made a pond appear. A great clump of lotuses grew in it, and there was one particularly large and beautiful lotus flower. “Sit here, brother,” he said, “and look at this flower.” And leaving the monk, he went back to his perfumed chamber.

That monk gazed and gazed at that flower. The Blessed One made it slowly decay. So as the monk looked at it, the flower began to fade. The petals fell off, beginning at the rim, until they were all gone. Then the stamens fell away, and only the pod was left. As he watched the monk thought to himself, “This lotus flower was lovely and fair. Yet now its color is gone and only the pod is left standing. Just as this lotus has decayed, this will happen to my body. All compounded things are subject to change. They are inconstant and impermanent!” And with that thought he attained his first insight.

Knowing that the monk’s mind had attained this insight, the Master, seated as he was in his perfumed chamber, projected a radiant image of himself and uttered this stanza:

Pluck out conceit, just as you would pluck

The autumn water lily. Set your heart

On nothing but this, the perfect Path of Peace,

And that end to suffering that the Buddha taught.

At the close of this stanza, that monk won Arahantship. At the thought that he would never be born again, never be troubled with existence ever again, he burst into a heartfelt utterance beginning with these stanzas. He who has lived his life, whose thought is ripe:

He who is purged and free from all defilements,

Wears his last body; he whose life is pure,

Reigns over his senses as a sovereign lord,

He, like the moon that wins her way at last

From Rāhu’s jaws, has won supreme release.

The foulness which enveloped me, which brought

Delusion’s utter darkness, I dispelled;

As the beaming sun with a thousand rays

Lights up heaven with a flood of light.

(Rāhu was a kind of Titan who was thought to cause eclipses by temporarily swallowing the sun and moon.)

After this and with renewed utterances of joy, he went to the Blessed One and saluted him. The Elder, too, came, and after due salutation to the Master went away with his companion.

When news of all this spread among the Saṇgha, they gathered together in the Dharma Hall and praised the virtues of the Lord of Wisdom, saying, “Sirs, by not knowing the hearts and thoughts of men, the Elder Sāriputta was ignorant of his companion’s disposition. But the Master knew, and in a single day our brother was able to attain Arahantship. Oh, the marvelous powers of a Buddha are great!”

Entering and taking the seat set ready for him, the Master asked, “What are you talking about, brothers?”

“Nothing else, Blessed One, then this: that you alone knew the heart and the thoughts of the companion of the Captain of the Faith.”

“This is no marvel, brothers, that I, as Buddha, should now that monk’s disposition. Even in bygone days I knew it.” And, so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares. In those days the Bodhisatta used to be the King’s minister in things both worldly and spiritual. At this time some people had washed a horse, a sorry beast, at the bathing place of the King’s war horse. And when the groom led the war horse down to the same water, the animal was so insulted that he would not go in. So the groom went off to the King and said, “Please your Majesty, your war horse will not take his bath.”

Then the King sent the Bodhisatta, saying, “Go, wise one, and find out why the animal will not go into the water.”

“Very good, sire,” said the Bodhisatta, and he went down to the waterside. There he examined the horse, and, finding it was not sick, he tried to determine what the reason was. At last he understood that some other horse must have been washed there, and that the war horse had been so insulted that he would not go into the water. So he asked the grooms what animal they had washed first in the water. “Another horse, my lord. It was an ordinary animal.”

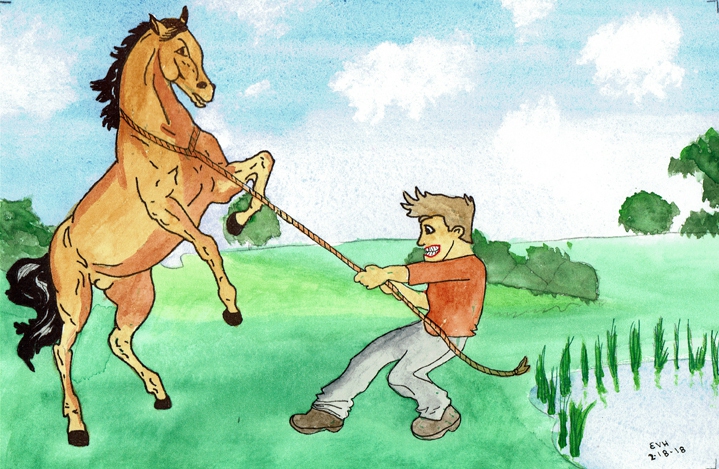

Figure: The Reluctant (and Snobby!) Horse

“Ah, his arrogance has caused him to be so offended that he will not go into the water,” the Bodhisatta said to himself. “The thing to do is to wash him somewhere else.” So he said to the groom, “A man gets tired, my friend, of even the best food if he has it all the time. And that’s how this horse is. He has been washed here so many times. Take him somewhere else and bathe him there.” And so saying, he repeated this stanza:

Change the spot, and let the war horse bathe

Now here, now there, with a constant change of scene.

For even the finest food bores a man at last.

After listening to his words, they led the horse off elsewhere, and watered and bathed him. And while they were washing the animal down afterwards, the Bodhisatta went back to the King. “Well,” said the King, “has my horse been watered and bathed, my friend?”

“He has, sire.”

“Why wouldn’t he do it before?”

“For the following reason,” said the Bodhisatta, and he told the King the whole story. “What a clever fellow he is,” said the King. “He can read even read the mind of an animal.” And he gave great honor to the Bodhisatta, and when his life ended he passed away to fare according to his karma. The Bodhisatta also passed away to fare likewise according to his karma.

When the Master ended his lesson and had repeated what he had said about his knowledge, in the past as well as the present, of that monk’s disposition, he showed the connection. He identified the birth by saying, “This monk was the war horse of those days. Ānanda was the King, and I was the wise minister.”