Jataka 28

Nandivisāla Jātaka

The Bull Who Won the Bet

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

The subject of proper speech is a constant theme in the Buddha’s teachings. He gives a great deal of advice on what is proper to say and when it is the right time to say it. We probably do more harm with our careless speech than with anything else we do. It is a difficult skill to master, and it is one that requires constant attention.

“Speak only words of kindness.” The Master told this story at Jetavana. It is about harsh words spoken by the Six (a group of six monks who were notorious for constantly breaking the monastic rules). For in those days the Six, when they disagreed with respectable monks, used to taunt, revile and jeer them, and torment them with abuse. The monks reported this to the Blessed One, who sent for the Six and asked them whether this charge was true. On their admitting its truth, he rebuked them, saying, “Monks, harsh words offend even animals. In bygone days an animal caused a man who used harsh language to lose a thousand gold coins.” And, so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time at Takkasilā in the land of Gandhāra there was a king reigning there, and the Bodhisatta was born as a bull. When he was quite a tiny calf, he was presented to a brahmin by his owners. They were known to give presents of oxen to holy men. The brahmin called it Nandi Visāla (Great Joy), and he treated it like his own child. He fed the young bull on rice pudding and fine rice. When the Bodhisatta grew up, he thought to himself, “I have been brought up by this brahmin with great care, and there is not another bull in all India that is as strong as I am. Perhaps I could repay the brahmin by a show of my strength.” Accordingly, one day he said to the brahmin, “Go, brahmin, to some merchant who is rich in herds and bet a thousand gold pieces that your bull can draw a hundred loaded carts.”

The brahmin found such a merchant and got into a discussion with him as to whose oxen in town were the strongest. “Oh, so-and-so’s, or so-and-so’s,” said the merchant. “But,” he added, “there are no oxen in the town that can compare with mine for real strength.”

The brahmin replied, “I have a bull who can pull a hundred loaded carts.”

“Where is such a bull to be found?” laughed the merchant.

“I’ve got him at home,” said the brahmin.

“Make it a bet.”

“Certainly,” said the brahmin, and he bet a thousand gold pieces.

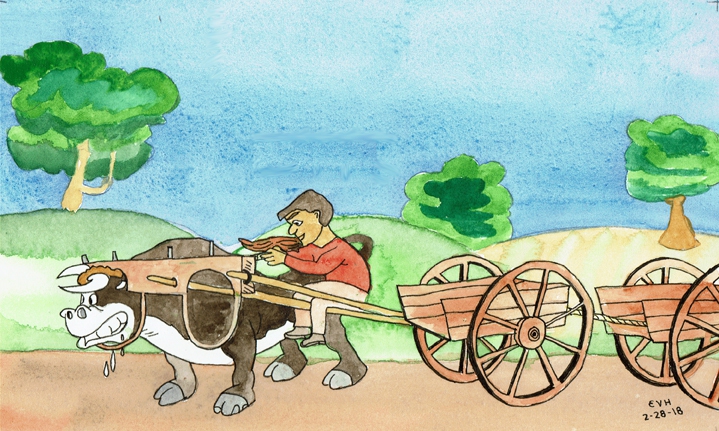

Then he loaded a hundred carts with sand, gravel, and stones, and leashed the lot together, one behind the other, by cords from the axle of the one in front to the one behind it. Then he bathed Nandi Visāla, gave him a measure of perfumed rice to eat, hung a garland round his neck, and harnessed him to the leading cart. The brahmin sat on the pole, and waved his whip in the air, shouting, “Now then, you scoundrel! pull them along, you scoundrel!”

“I’m not a scoundrel,” thought the Bodhisatta, and so he planted his four feet like so many posts and did not budge an inch.

The merchant made the brahmin pay the thousand gold pieces. His money gone, the brahmin took his bull and went home. There he lay down on his bed in agony and grief. When Nandi Visāla walked in and found the brahmin in such grief, he went up to him and asked if the brahmin were taking a nap. “How could I take a nap when I have lost a thousand gold pieces?!”

“Brahmin, in all the time that I have lived in your house, have I ever broken a pot, or squeezed up against anybody, or made a mess?”

“Never, my child.”

“Then, why did you call me a scoundrel? It’s you who are to blame, not me. Go and bet him two thousand gold pieces this time. Only do not call me scoundrel again.”

When he heard this, the brahmin went off to the merchant and bet two thousand gold pieces. Just as before, he leashed the hundred carts to one another and harnessed Nandi Visāla, very well groomed and looking fine, to the leading cart. If you ask how he harnessed him, well, he did it in this way. First, he fastened the yoke on to the pole. Then he put the bull in on one side and fastened a smooth piece of wood from the cross yoke on to the axle so that the yoke was tight and could not bend. Thus a single bull could pull a cart that was designed to be pulled by two oxen.

So now seated on the pole, the brahmin stroked Nandi Visāla on the back and called on him in this style, “Now then, my fine fellow! Pull them along, my fine fellow!” With a single pull the Bodhisatta tugged along the whole string of one hundred carts until the last cart stood where the first cart had started. The merchant, rich in herds, paid up the two thousand gold pieces. Other people, too, gave large sums to the Bodhisatta and all of it went to the brahmin. Thus he gained greatly because of the Bodhisatta.

Figure: The Mighty Bull Pulls One Hundred Carts!

In this way he rebuked the Six by showing that harsh words please no one. The Master, as Buddha, uttered this stanza:

Speak only words of kindness, never words

Unkind. For he who spoke kindly, he moved

A heavy load, and brought him wealth, for love.

When he ended his lesson about speaking only words of kindness, the Master identified the birth by saying, “Ānanda was the brahmin of those days, and I myself Nandi Visāla.”