Jataka 75

Maccha Jātaka

The Fish Story

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

Over the centuries, as religions competed with each other, many stories were told to prove the worthiness of their founders. This is probably one of them. And this is not the only story in the Buddhist canon in which the Buddha is said to have brought rain to a drought ridden community.

There is one part of this story that seems out of character. While it makes sense that the Bodhisatta would try to save living beings, it does not make sense for him to call upon a god to make others – in this case the crows – suffer.

Note that in India, Pajjunna is the god of rain.

“Pajjunna, thunder!” The Master told this story while at Jetavana. It is about a rainfall that he caused. For in those days, so it is said, no rain fell in Kosala. The crops withered, and the ponds, tanks, and lakes dried up. Even the pool of Jetavana by the embattled gateway was dry. The fish and tortoises buried themselves in the mud. Then the crows and hawks came with their lance-like beaks, and they busily picked them out from the mud, writhing and wriggling, and devoured them.

As he saw how the fish and the tortoises were being destroyed, the Master's heart was moved with compassion. He exclaimed, “This day I must cause rain to fall.” So, when the night grew into day, after attending to his bodily needs, he waited until it was the proper hour to go on alms round. And then, surrounded by members of the Saṇgha, and perfect with the perfection of a Buddha, he went into Sāvatthi for alms. On his way back to the monastery in the afternoon, he stopped at the steps leading down to the tank of Jetavana and addressed the Elder Ānanda.

“Bring me a bathing robe, Ānanda, for I will bathe in the tank of Jetavana.”

“But surely, sir,” the Elder replied, “the water is all dried up and there is only mud.”

“A Buddha’s power is great, Ānanda. Go, bring me the bathing robe,” the Master said.

So the Elder went and brought the bathing robe which the Master put on, using one end to go around his waist, and covering up his body with the other. So dressed, he stood on the tank steps and exclaimed, “I would gladly bathe in the tank of Jetavana.”

That instant the golden throne of Sakka grew hot beneath him, and Sakka looked to see why. Realizing what was the matter, he summoned the King of the Storm Clouds and said, “The Master is standing on the steps of the tank of Jetavana and wishes to bathe. Quickly pour down rain in a single torrent all over the kingdom of Kosala.” Obedient to Sakka’s command, the King of the Storm Clouds dressed himself in one cloud as an under garment and another cloud as an outer garment, and chanting the rain song, he dashed eastward. And lo! He appeared in the east as a cloud as big as a threshing floor (a floor where rice was threshed). It grew and grew until it was as big as a hundred, as a thousand, threshing floors. There was thunder and lightning, and bending down his face and mouth, he deluged all Kosala with torrents of rain. The downpour was constant, quickly filling the tank of Jetavana and stopping only when the water was level with the topmost step.

Then the Master bathed in the tank, and coming up out of the water, he put on his orange colored robes. He adjusted his Buddha robe around him, leaving one shoulder bare. Dressed like this, he set forth, surrounded by the Saṇgha. He went into his Perfumed Chamber, fragrant with sweet-smelling flowers. Here he sat on the Buddha seat. And when the monks had performed their duties, he rose and exhorted them from the jeweled steps of his throne, and then dismissed them from his presence. Passing now within his own sweet-smelling chamber, he stretched himself, lion-like, on his right side.

Later the monks gathered together in the Dharma Hall. They said, “When the crops were withering, when the pools were drying up and the fish and tortoises were in a terrible plight, in his compassion he came forth as a savior. Dressed in a bathing robe, he stood on the steps of the tank of Jetavana and made the rain pour down from the heavens until it seemed like it would overwhelm all Kosala. And by the time he returned to the monastery, he had freed all the fish and tortoises from their suffering both of mind and body.”

This was their conversation when the Master came out of his Perfumed Chamber into the Dharma Hall. He asked them what they were discussing, and they told him. “This is not the first time, monks,” the Master said, “that the Blessed One has made the rain fall in the hour of need. He did the same thing when born into the animal realm, in the days when he was King of the Fish.” And so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time, in that same kingdom of Kosala (and at Sāvatthi too), there was a pond where the tank of Jetavana now is. This pond was fenced in by a tangle of climbing plants. The Bodhisatta lived there. He had been born as a fish. And then, as now, there was a drought. The crops withered. Water gave out in the tank and pool, and the fish and tortoises buried themselves in the mud. Likewise, when the fish and tortoises of this pond had buried themselves in its mud, the crows and other birds, flocking to the spot, picked them out with their beaks and devoured them.

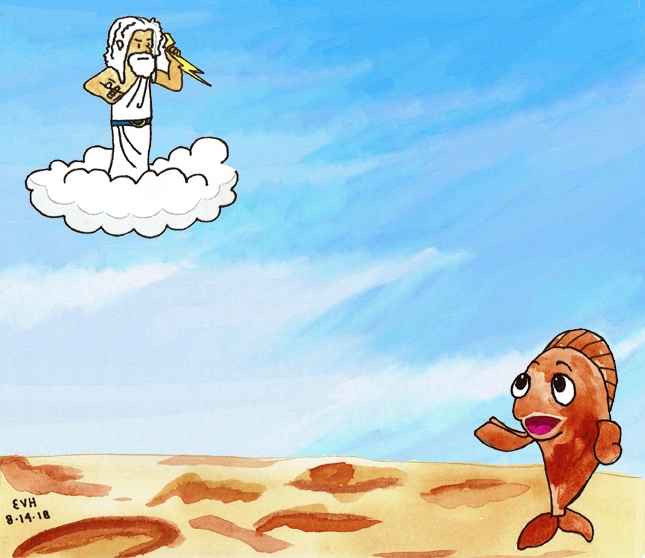

Seeing the fate of his kin, and knowing that no one but he could save them in their hour of need, the Bodhisatta resolved to make a solemn Profession of Goodness. By its power he would make a rain fall from the heavens in order to save his kin from certain death. So, pulling back the black mud, he came up, a mighty fish, blackened with mud like a casket of the finest sandalwood that has been smeared with oil. Opening his eyes which were like sparkling rubies, and looking up to the heavens, he thus implored Pajjunna, King of Devas, “My heart is heavy for my kin’s sake, my good Pajjunna. Why is it that when I, who am virtuous, am distressed for my kin, you do not send rain from the heavens? For even though I have been born where it is customary to prey on one’s kin (the animal realm), I have never eaten any fish from the time of my youth, even one the size of a grain of rice. Nor have I ever robbed a single living creature of its life. By the truth of this, my declaration, I call upon you to send rain and help my kin.” Then he called to Pajjunna, King of Devas, as a master might call to a servant, in this stanza:

Pajjunna, thunder! Baffle and thwart the crow!

Breed sorrow on him. Ease me from woe!

In this way, as a master might call to a servant, the Bodhisatta called to Pajjunna. This caused heavy rains to fall and relieved many from the fear of death. And when his life closed, he passed away to fare according to his karma.

Figure: The Muddy Fish Implores the Rain God

“So this is not the first time, monks,” the Master said, “that the Blessed One has caused the rain to fall. He did so in bygone days as well, when he was a fish.” His lesson ended, he identified the birth by saying, “The Buddha's disciples were the fish of those days, Ānanda was Pajjunna, King of Devas, and I was the King of the Fish.”