Jataka 93

Vissāsabhojana Jātaka

The Fare of Trust

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a story about good judgment. The meditation teacher Larry Rosenberg says that he is amazed at how many otherwise intelligent, capable, competent people check their common sense at the door when it comes to their spiritual practice. You can expand that observation to other parts of our lives as well. The Buddha here is not saying to be unnecessarily skeptical or paranoid; he is simply saying that in all situations of our lives we should use good judgment.

“Trust not the trusted.” This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana. It is about taking things on trust.

Tradition tells us that in those days the monks, for the most part, used to rest content if anything was given to them by their mothers or fathers, brothers or sisters, or uncles or aunts, or other family members. Arguing that in their lay state they had routinely received things from the same hands, they, as monks, showed no reservations or caution before using food, clothing, and other requisites that their relations gave them. Observing this the Master felt that he must teach the monks a lesson. So he called them together, and said, “Monks, whether the giver is a relation or not, you must still use good judgment. The monk who uses the requisites that are given to him without good judgment may condemn himself to a subsequent existence as an ogre or as a ghost. Use without good judgment is like taking poison, and poison kills just the same, whether it is given by a relative or by a stranger. There were those in bygone days who actually did take poison because it was offered by those near and dear to them, and thereby they met their end.” So saying, he told the following story of the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was a very wealthy merchant. He had a herdsman who, when the corn was growing thick, drove his cows to the forest and kept them there in a barn, bringing the produce from time to time to the merchant.

Now near to the barn in the forest there lived a lion. The cows were so afraid of the lion that they gave very little milk. So when the herdsman brought in his ghee one day, the merchant asked why there was so little milk. Then the herdsman told him the reason. “Well, has the lion formed an attachment to anything?”

“Yes, master. He is fond of a doe.”

“Could you catch that doe?”

“Yes, master.”

“Well, catch her, and rub her all over with poison and sugar and let her dry. Keep her a day or two and then turn her loose. Because of his affection for her, the lion will lick her all over with his tongue and die. Take his hide with the claws and teeth and fat and bring them back to me.”

So saying, he gave deadly poison to the herdsman and sent him off. With the aid of a net which he made, the herdsman caught the doe and carried out the Bodhisatta’s orders.

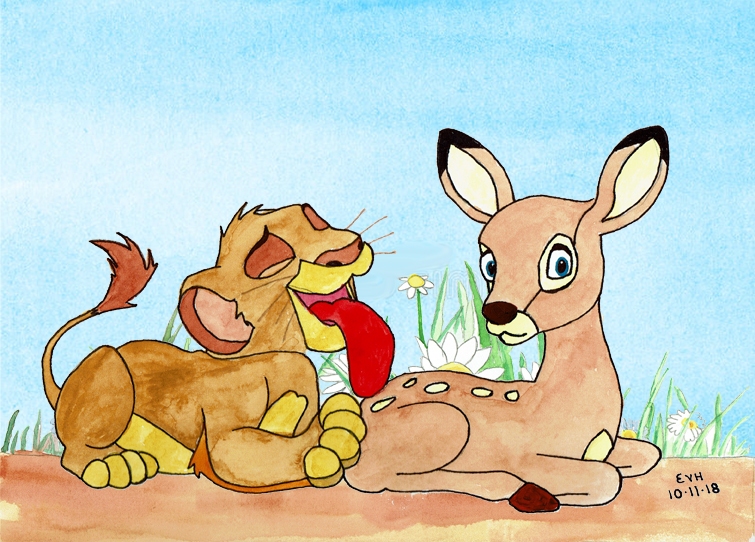

Figure: Fawning Over the Poison Deer

As soon as he saw the doe again, the lion, in his great love for her, licked her with his tongue so that he died. And the herdsman took the lion’s hide and the rest and brought them to the Bodhisatta, who said, “Affection for others should be shunned. Mark how, for all his strength, the king of beasts, the lion, was led by his sinful love for a doe to poison himself by licking her, causing him to die.” So saying, he uttered this stanza for the instruction of those gathered round:

Trust not the trusted, nor the untrusted trust;

Trust kills; through trust the lion bit the dust.

Such was the lesson that the Bodhisatta taught to those around him. After a life spent in charity and other good works, he passed away to fare according to his karma.

His lesson ended, the Master identified the birth by saying, “I was the merchant of those days.”