Jataka 264

Pali Jātaka

The Great King Panāda

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is quite an interesting little tale. It features some fascinating aspects of the Buddha’s Dharma.

The first is the use of psychic powers. Very early on in the life of the Saṇgha, the Buddha discouraged the display of psychic powers. In fact, this is forbidden in the Vinaya. However, before that they were used, and the possession of psychic powers is prevalent in the Canon.

Another feature of this story is merit from a previous life. This is why the hero of the story—Bhaddaji—is able to become an arahant so easily. This is important to those of us who practice today. The cultivation of virtue and the performance of kind acts may have enormous value to us in the future, either in this life or a future life.

“’Twas King Panāda.” The Master told this story when he was settled on the bank of the Ganges. It is about the miraculous power of the Elder Bhaddaji.

On one occasion, when the Master had spent the rains retreat at Sāvatthi, he thought he would show kindness to a young gentleman named Bhaddaji. So with all the monks who were with him, he made his way to the city of Bhaddiya. He stayed in Jātiyā Grove (Jātiyāvana) for three months, waiting until the young man would mature and perfect his knowledge. Now young Bhaddaji was a magnificent person. He was the only son of a rich merchant in Bhaddiya. He had a fortune of eighty crores (800 million rupees). He had three houses for each of the three seasons. He stayed in each of them for four months. After spending this period in one of them, he would move with all his kith and kin to another house with the greatest pomp and ceremony. On these occasions the whole town was aflutter to see the young man’s magnificence. And between these houses he used to erect seats in circles on circles and tiers above tiers so that people could sit and watch the spectacle.

When the Master had been there for three months, he informed the townspeople that he intended to leave. They begged him to wait until the next day. On the following day, the townsfolk collected magnificent gifts for the Buddha and his attendant monks. They set up a pavilion in the midst of the town, decorating it and laying out seats. Then they announced that the time had come. The Master went with his company and they took their seats there. Everybody gave generously to them. After the meal was over, the Master gave thanks to them in a voice as sweet as honey.

At the same time young Bhaddaji was moving from one of his residences to another. But on that day not a single soul came to see his splendor. It was only his own people who were with him. So he asked his people why this was. Usually the whole city was excited to see him pass from house to house. But today there was nobody there but his own followers! What could be the reason?

The reply was, “My lord, the Supreme Buddha has been spending three months near the town, and today he is leaving. He has just finished his meal and is giving a discourse. All the town is there listening to his words.”

“Oh, very well. Then we will go and hear him too,” said the young man. So, in a blaze of ornaments and with his crowd of followers about him, he went and stood on the edge of the crowd. As he heard the discourse he abandoned all off his defilements. He attained a full awakening and became an arahant.

The Master, addressing the merchant of Bhaddiya, said, “Sir, your son, in all his splendor, while hearing my discourse has become an arahant. On this day he should either embrace the holy life or enter nirvāṇa.”

(Traditionally in Buddhism when a lay person becomes an arahant, they either ordain as a monk or die. This is because an arahant no longer has any interest in worldly matters, so they either attain nirvāṇa or remain in the Saṇgha in order to teach others.)

“Sir,” he replied, “I do not wish my son to enter nirvāṇa. Admit him to the Saṇgha. Once this is done, come with him to my house tomorrow.”

The Blessed One accepted this invitation. He took the young gentleman to the monastery, admitting him to the Saṇgha and giving him both the lower and higher ordination. For the next week the youth’s parents showed generous hospitality to him.

After remaining for those seven days, the Master went on an alms-pilgrimage. He took the young man with him and arrived at a village called Koṭi. The villagers of Koṭi gave generously to the Buddha and his followers. At the end of this meal, the Master began to express his thanks. While this was being done, the young gentleman went outside the village. He went to a landing-place on the Ganges and sat down under a tree. There he entered jhāna (meditative absorption), thinking that he would rise as soon as the Master arrived. When the Elders of the Saṇgha approached, he did not rise, but he got up as soon as the Master came. The unenlightened people were angry because he behaved as though he were a monk of old standing, not rising up even when he saw the eldest monks approach.

Next the villagers constructed rafts. This done, the Master asked where Bhaddaji was. “There he is, Sir.” “Come, Bhaddaji, come aboard my raft.” The Elder arose and followed him to his raft. When they were in mid-river, the Master asked him a question.

“Bhaddaji, where is the palace where you lived when Great Panāda was King?”

“Here, under the water,” was the reply. The unenlightened people said to each other, “Elder Bhaddaji is claiming that he is an arahant!” Then the Master told him to dispel the doubt of his fellow students.

In the next moment, the Elder bowed to his Master. Then he used his psychic power to put the whole palace on his finger. He rose up in the air taking the palace with him. The palace covered an area of 25 leagues (about 140 kilometers or 86 miles). Then he made a hole in it and showed himself to the present inhabitants of the palace below. Then he tossed the building above the water first one league, then two, then three. Those who had been his kinfolk in this former existence had now become fish or tortoises, water-snakes or frogs because they loved the palace so much. Because of this, they had been reborn in the very same place. They wriggled out of it when it rose up and tumbled back into the water again. When the Master saw this, he said, “Bhaddaji, your relations are in trouble.” At his Master’s words the Elder let go of the palace, and it sank back into the place where it had been before.

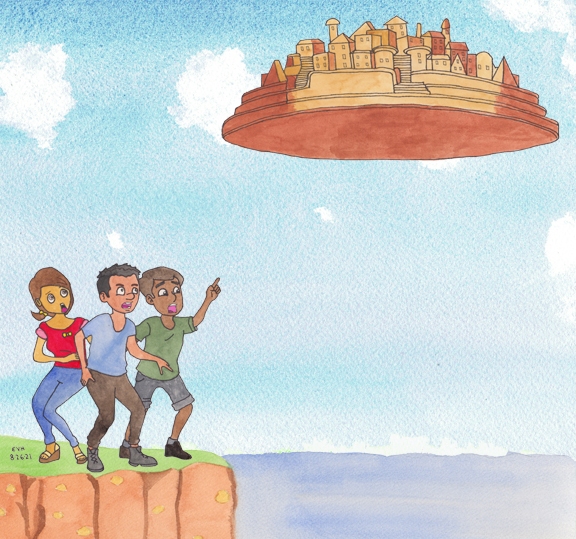

Figure: The Elder Bhaddaji is the man!

The Master passed over to the far side of the Ganges. There they prepared a seat for him on the river bank. He sat on this seat like the sun freshly arisen pouring forth its rays. Then the monks asked him when it was that the Elder Bhaddaji had lived in that palace. The Master answered, “In the days of the Great King Panāda.” And he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time, a certain Suruci was the King of Mithilā, which is a town in the kingdom of Videha. He had a son who was also named Suruci. In turn he also had a son, the Great Panāda. They obtained possession of that palace. They got possession of it because of an auspicious deed done in a former life. A father and son had made a hut of leaves with canes and branches of a fig tree as a dwelling for a Paccekabuddha.

The rest of the story will be told in the Suruci Birth (Jātaka 489).

The Master, having finished telling this story uttered these stanzas in his perfect wisdom:

“’Twas King Panāda who this palace had,

A thousand bowshots high, in breadth sixteen.

A thousand bowshots high, in banners clad,

A hundred storys, all of emerald green.

“Six thousand men of music to and fro

In seven companies did dance withal,

As Bhaddaji has said, ‘twas even so,

I, Sakka, was your slave, at beck and call."

At that moment the unenlightened people became resolved of their doubt.

When the Master ended this discourse, he identified the birth: “Bhaddaji was the Great Panāda, and I was Sakka.”