Jataka 278

Mahisa Jātaka

The Buffalo

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is the first Jātaka Tale I ever heard. It is rendered and illustrated quite beautifully in the book “The Magic of Patience” by Rosalyn White.

This version contains one implication that is a little misleading. It may appear that the good buffalo is suggesting that karma is punitive. Many people think this, but that is a misunderstanding of the Buddha’s teaching on karma. It is more that the good buffalo sees that the insolent monkey will—inevitably—fall prey to his poor behavior.

“Why do you patiently endure?” The Master told this story while he was at Jetavana. It is about a certain insolent monkey.

At Sāvatthi, we are told, there was a monkey from a certain family. One day it ran into the elephant’s stable, perched on the back of a virtuous elephant, and voided excrement. Then he leaped up and down the elephant’s back. The elephant, being both virtuous and patient, did nothing.

But one day, instead of the virtuous and patient elephant, there stood a wicked young one in his place. The monkey thought it was the same elephant and climbed on its back. The elephant seized him in his trunk, threw him to the ground, and trampled him to pieces.

This became known in a meeting of the Saṇgha, and one day they began to discuss it. “Brother, have you heard how the insolent monkey mistook a had elephant for a good one, climbed on his back, and how he lost his life because of it?” The Master came in and asked, “Brothers, what are you discussing as you sit here?” And when they told him, he said “This is not the first time that this insolent monkey behaved like this. He did the same before.” And he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was the King of Benares, the Bodhisatta was born in the Himalaya region as a buffalo. He grew up big and strong. He ranged the hills and mountains, peaks and caves, and many forests and woods.

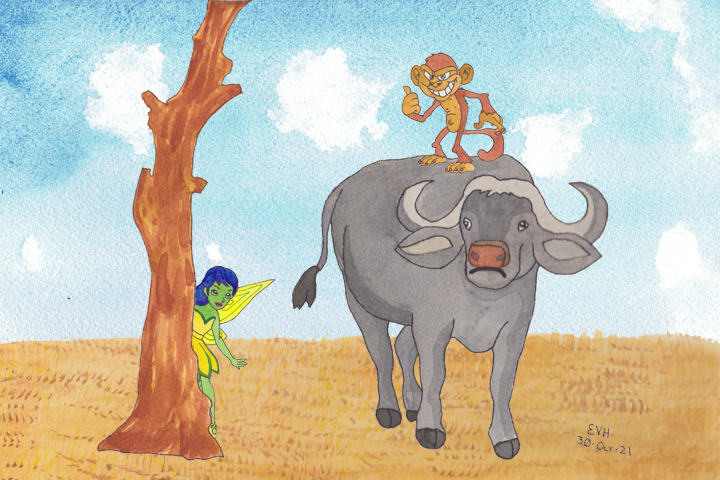

Once, as he went traveling about, he saw a pleasant tree. He took his food and stood under it. Then an insolent monkey came down out of the tree, and—getting on his back—voided excrement. Then he took hold of one of the buffalo’s horns, and swung down from it by his tail, frolicking about. The Bodhisatta, being full of patience, kindness, and mercy, took no notice at all of his misconduct. This monkey continued this behavior over and over again.

But one day, the spirit that belonged to that tree, stood on the tree trunk. She said, “My lord buffalo, why do you put up with the rudeness of this bad monkey? Put a stop to him!” and enlarging upon this theme, she repeated the first two verses as follows:

“Why do you patiently endure each abuse

This mischievous and selfish ape may choose?

“Crush underfoot, impale him with your horn!

Stop him or even children will show scorn.”

Figure: Why do you patiently endure?

The Bodhisatta, on hearing this, replied, “If, tree sprite, I cannot endure this monkey’s ill-treatment without abusing his birth, lineage, and powers, how can my wish to perfect virtue ever come true? But the monkey will do the same to any other buffalo, thinking him to be like me. And if he does it to any fierce buffalos, they will destroy him. Then I shall be delivered both from pain and from shame. This is not my wish. It is simply the outcome of his behavior. We reap the results of the quality of our conduct, good or bad.” And saying this he repeated the third verse:

“If he treats others as he now treats me,

They will destroy him; then I shall be free.”

A few days later the Bodhisatta went away, and another buffalo—a savage beast—went and stood in his place. The wicked monkey, thinking it to be the previous buffalo, climbed upon his back and behaved as he had before. This buffalo threw him to the ground, drove his horn into the monkey’s heart, and trampled him to pieces under his hoofs.

When the Master had ended this teaching, he taught the Four Noble Truths. Then he identified the birth: “At that time the bad buffalo was the one who is now the bad elephant. The bad monkey is the same, and I was the virtuous, noble buffalo.”