Jataka 289

Nāna Chanda Jātaka

The Good Priest

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

There are a number of Jātaka Tales like this one in which a member of the King’s court falls out of favor, but then is able to regain their position by a virtuous act. It reminds us to be patient, to always do the right thing, to be kind and compassionate, and to be forgiving.

“We live in one house.” The Master told this story at Jetavana. It is about the venerable Ānanda’s receiving a great boon. The circumstances will be explained in the Juṇha Birth (Jātaka 456).

Now once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born as the son of his Queen Consort. He grew up, was educated at Takkasilā University, and became King on his father’s death.

There was a family priest of his father’s who had been removed from his post, and being very poor, he lived in an old house.

One night it happened that the King was walking about the city in disguise in order to explore it. Some thieves, their work done, had been drinking in a wine shop, and they were carrying some more liquor home in a jar. They saw him there in the street, and crying, “Halloo, who are you?” they knocked him down and took his upper robe.

The aforesaid priest happened at the time to be in the street observing the constellations. He saw how the King had fallen into unfriendly hands and called out to his wife. She came quickly, asking what it was. He said, “Wife, our King has fallen into the hands of his enemies!”

“Why, your reverence,” she said, “what dealings have you with the King? His brahmins will see to it.”

The King heard them say this.

He called out to the thieves, “I’m a poor man, masters. Take my robe and let me go!” He said this again and again, and finally they let him go out of pity. He took note of where they lived and turned back again.

The brahmin said to his wife, “Wife, our King has gotten away from the hands of his enemies!” The King heard this as before and entered his palace.

When the dawn came, the King summoned his brahmins and asked them a question.

“Have you been taking celestial observations?”

“Yes, my lord.”

“Was it lucky or unlucky?”

“Lucky, my lord.”

“No darkness?”

“No, my lord, none.”

Then the King said, “Go and fetch the brahmin from such and such a house,” giving them directions.

So they fetched the old chaplain, and the King proceeded to question him.

“Did you take celestial observations last night, master?”

“Yes, my lord, I did.”

“Was there any darkness?”

“Yes, my lord. Last night you fell into the hands of your enemies, and in a moment you got free again.”

The King said, “That is the kind of man a stargazer ought to be.”

He dismissed the other brahmins. He told the old priest that he was pleased with him and told him to ask for a boon. The man asked for a chance to consult with his family, and the King allowed him to do so.

The man summoned his wife and son, his daughter-in-law and a maidservant, and he put the matter before them. “The King has granted me a boon. For what shall I ask?”

The wife said, “Get me 100 dairy cows.”

The son, named Chatta, said, “For me, I would like a chariot drawn by fine lily-white thoroughbreds.”

Then the daughter-in-law said, “I would like all manner of trinkets, earrings set with gems, and so forth!”

And the maidservant—whose name was Puṇṇā—said, “For me, I would like a pestle and mortar, and a winnowing basket.”

(Winnowing is the process whereby chaff is removed from grain. It follows threshing.)

The brahmin himself wanted to have the revenue of a village as his boon. So when he returned to the King, the King wanted to know whether his wife had been consulted. The brahmin replied, “Yes, my lord King. But those who I consulted are not all of one mind,” and he repeated a couple of stanzas:

“We live in one house, O King,

But we don’t all want the same thing.

My wife’s wish—a hundred kine,

A prosperous village is mine;

The student’s wish is carriage and horses,

Our daughter wants an earring fine.

While poor little Puṇṇā, the maid,

Wants pestle and mortar, she said!”

(A “kine” is a cow.)

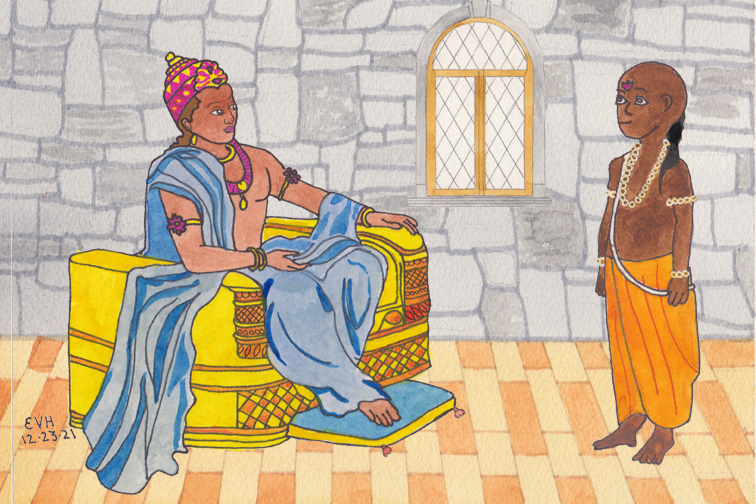

Figure: The King and the chaplain

“All right,” said the King, “they shall all have what they want,” and he repeated the remaining lines:

“Give a hundred cows to the wife,

To the goodman a village for life,

and a jeweled earring to the daughter,

A carriage and pair be the student’s share,

And the maid gets her pestle and mortar.”

Thus the King gave the brahmin what he wished and great honor besides. And bidding him to attend to the King’s business, he kept the brahmin as a member of his court.

When the Master ended this discourse, he identified the birth: “At that time the brahmin was Ānanda, and I was the King.”