Jataka 320

Succaja Jātaka

The Story of Succaja

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story has some interesting elements. First of all the man who refuses to give to his wife is not entirely heard-hearted. It turns out that in her request, he refuses because he does not want to promise something and then not be able to deliver. He couches it in terms of honesty. But of course the Bodhisatta reminds him of her service to him, and thus affects her fair treatment. But even she is able to acknowledge and praise him for his respect for honesty.

“He might give.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about a certain landowner. According to the story, he went to a village with his wife to collect a debt. He took a cart in payment for what was due to him. He left it with a certain family intending to retrieve it later on.

While they were on the road to Sāvatthi, they saw a mountain. The wife asked him, “Suppose this mountain were to become all gold, would you give me some of it?” “Who are you?” he replied. "I would not give you an ounce.” “Alas!” she cried, “he is a hard-hearted man. Even if the mountain should become pure gold, he would not give me an ounce.” And she was very unhappy.

When they got near to Jetavana they felt thirsty, so they went into the monastery to get some water to drink. The Master saw in them a capacity for liberation. He sat in the cell of his perfumed chamber awaiting their arrival. He emitted the six-colored rays of Buddhahood. And after they had quenched their thirst, they went to the Master. They respectfully saluted him and sat down. The Master, after the usual kindly greetings, asked them where they had been. “We have been, reverend sir, to collect a debt.”

“Lay Sister,” he said, “I hope your husband is anxious for your welfare and ready to do you a kindness.”

“Reverend sir,” she replied, “I am very loving to him, but he has no love for me. Today we saw a mountain. I asked him, ‘Suppose it were all pure gold, would you give me some?’ He answered, ‘Who are you? I would not give you an ounce.’ This is how hard-hearted he is.”

“Lay sister,” the Master said, “he may talk like this. But whenever he calls to mind your virtues, he is ready to give you command over everything.”

“Tell us about it, your reverence,” they cried, and at their request he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was his minister, rendering him all due service. One day the King saw his son—who acted as his viceroy—coming to pay his respects to him. He thought to himself, “This fellow may harm me if he gets the opportunity.” So he sent for him and said, “As long as I live, you cannot reside in this city. Live somewhere else, and at my death you can take over the rule of the kingdom.” He agreed to these conditions, and bidding his father farewell, he started from Benares with his chief wife.

They came to a frontier village. There he built himself a hut of leaves in a wood and stayed there, supporting life on wild roots and fruit. By and bye the King died. The young viceroy, from his observation of the stars, knew of his father’s death. So he set off for Benares.

Subsequently a mountain came into sight. His wife said to him, “Supposing, sir, that mountain turned into pure gold. Would you give me some of it?” “Who are you?” he cried, “I would not give you an ounce.” She thought, “I entered this forest from my love for him, not having the heart to desert him. And yet he speaks to me in this way. He is very hard-hearted. And if he becomes King, what good will he do me?” And her heart was in dispair.

When they reached Benares, he was established on the throne. He raised her to the dignity of chief Queen. But he merely gave her a ceremonial rank. Beyond this he paid her no respect or honor. He did not even acknowledge her existence. The Bodhisatta thought, “This Queen was a helpful companion to the King. She suffered the discomfort and pain of living with him in the wilderness. But he takes no account of this. He goes about taking his pleasure with other women. But I will bring it about that she will receive lordship over all.”

And with this thought, one day he went to see her. He saluted her and said, “Lady, we do not receive from you so much as a lump of rice. Why are you so hard-hearted? Why do you neglect us?”

“Friend,” she replied, “if I were to receive anything, I would give it you. But if I get nothing, what am I to give? What is the King likely to give me? On the road here, when asked, ‘If that mountain were all pure gold, would you give me anything?’ he answered, ‘Who are you? I would give you nothing.’”

“Well, could you repeat all this before the King?” he said.

“Why should I not, friend?” she answered.

“Then when I am next in the King’s presence,” he said, “I will ask and you will repeat it.”

“Agreed, friend,” she said.

So the Bodhisatta, when he next stood and paid his respects to the King, asked the Queen, “Are we not, lady, to receive anything from your hands?”

“Sir,” she answered, “when I get anything, I will give you something. But, what is the King likely to give me now? When we were coming from the forest and we saw a mountain, I asked him, ‘If that mountain were all pure gold, would you give me some of it?’ ‘Who are you?’ he said, ‘I will give you nothing.’ And in these words he refused to give what was easy to give.” To illustrate this, she repeated the first stanza:

He might give at little cost

What he would not miss, if lost.

Golden mountains I bestow,

He to all I ask says “No.”

The King—on hearing this—uttered the second stanza:

When you can, say “Yes, I will,”

When you cannot, promise nil.

Broken promises are lies,

Liars all wise men despise.

The Queen, when she heard this, raising her joined hands in respectful salutation, repeated the third stanza:

Standing fast in righteousness,

You, O prince, we humbly bless.

Fortune may all else destroy,

Truth is still your only joy.

The Bodhisatta, after hearing the Queen sing the praises of the King, set forth her virtues and repeated the fourth stanza:

Known to fame as peerless wife,

Sharing pain and woe of life,

Equal she to either fate,

Fit with even Kings to mate.

The Bodhisatta—in these words—sang the praises of the Queen, saying, “This lady, your majesty, in the time of your adversity, lived with you and shared your sorrows in the forest. You ought to do her honor.”

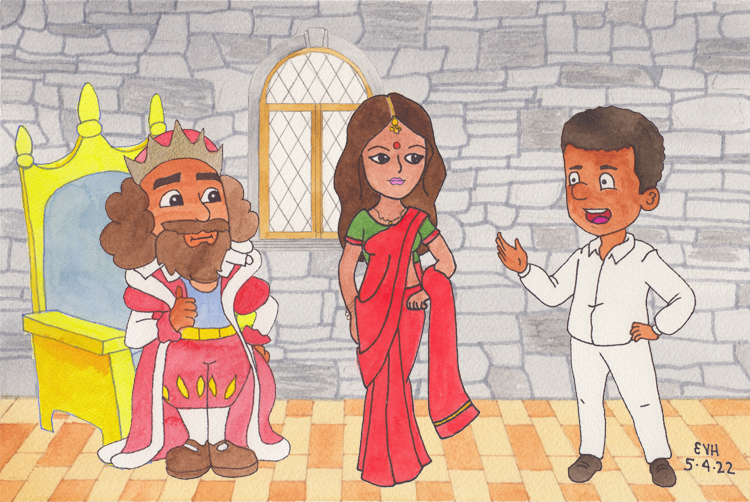

Figure: “You ought to do her honor.”

The King, at these words, called to mind the Queen’s virtues and said, “Wise sir, at your words I am reminded of the Queen’s virtues.” And so saying, he gave all power into her hand. Moreover he bestowed great power upon the Bodhisatta. “For it was by you,” he said, “I was reminded of the Queen’s virtues.”

The Master, having ended his lesson, taught the Four Noble Truths. At the conclusion of the teaching, the husband and wife attained to fruition of the First Path (stream entry). Then the Master identified the Birth: “At that time this landowner was the King of Benares, this lay sister was the Queen, and I was the wise councilor.”