Jataka 467

Kāma Jātaka

Passion and Lust

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This discourse has a parallel one in Jātaka 228, the Kāmanīta Jātaka. The theme is the disease that is sense desire and lust, and that the cure is wisdom and understanding.

“He that desires.” The Master told this story while he was at Jetavana. It is about a certain brahmin.

A brahmin, so they say, who lived at Sāvatthi, was felling trees on the bank of the Aciravatī River in order to clear the land for farming. The Master saw his destiny in the spiritual life when he visited Sāvatthi for alms. He stopped his search for alms in order to talk sweetly with him.

“What are you doing, brahmin?” he asked.

“Oh Gotama,” the man said, "I am clearing a space for farming.”

“Very good,” he replied, “go on with your work, brahmin.”

In the same manner the Master went and talked to him when the felled trunks were all taken away and the man had cleared his acre. He did likewise at plowing time and when he cleared irrigation ditches for water.

Now on the day of planting, the brahmin said, “Today, Oh Gotama, is my plowing festival. When this grain is ripe, I will give alms in plenty to the Saṇgha with the Buddha at its head.”

(The plowing festival was an annual event in India when the King did a ceremonial plowing.)

The Master accepted his offer and went away. On another day he came and saw the brahmin looking over the crop.

“What are you doing, brahmin?” he asked.

“Watching the crop, Oh Gotama!”

“Very good, brahmin,” the Master said, and away he went.

Then the brahmin thought, “How often Gotama the recluse comes this way! Without doubt he wants food. Well, I will give him food.”

On the day when this thought came into his mind, when he went home, there he found the Master. This caused great confidence to arise in the brahmin.

By and bye, when the crop was ripe, the brahmin resolved that tomorrow he would harvest the field. But while he lay in bed, in the upper reaches of the Aciravatī River a great rain poured down. This caused a flood, and the flood carried the whole crop away to the sea. Not one stalk was left.

When the flood subsided the brahmin looked over the destruction of his crops. He did not have the strength to stand. He pressed his hand to his heart for he was overcome with great sorrow. He went home weeping and lay down lamenting.

In the morning the Master saw this brahmin overwhelmed with his grief. He thought, “I will be the brahmin’s support.” So on the next day, on his return from his alms-round in Sāvatthi, he sent the Saṇgha back to the monastery. And accompanied by a junior monk, he visited the man’s house.

When the brahmin heard of his coming, he took heart, thinking, “My friend must be coming for a friendly talk.” The Master entered and he offered him a seat. He asked, “Why are you downhearted, brahmin? What has happened to upset you?”

“Oh Gotama!” the man said, from the time that I cut down the trees on the bank of the Aciravatī, you know what I have been doing. I have been going about promising gifts to you when that crop should be ripe. Now a flood has carried off the whole crop, away to the sea. Nothing is left at all! The grain has been destroyed to the amount of a hundred wagon-loads, and so I am deep in grief!”

“Why, will grieving bring back what is lost?”

“No, Gotama, it will not.”

“If that is so, why grieve? The wealth of beings in this world - or their grain - when they have it, they have it, and when it is gone, it is gone. All compounded things are subject to destruction. Do not brood over it.”

Thus comforting him, the Master repeated the Kama Sutta (SN 4.1) as appropriate to his case. At the conclusion of the Kama Sutta, the mourning brahmin was established in the Fruit of the First Path (stream-entry). The Master - having eased him of his pain - arose from his seat and returned to the monastery.

The entire town heard how the Master had found the brahmin pierced with the pangs of grief, how he had consoled him and established him in the Fruit of the First Path. The Saṇgha discussed it in the Dharma Hall. “Hear, Sirs! The Dasabala (the Buddha) made friends with a brahmin, grew intimate with him, and took his opportunity to declare the Dhamma to him. When pierced with the pangs of grief, he eased him of pain and established him in the Fruit of the First Path!” The Master came in and asked, “What are you discussing, monks, as you sit here together?” They told him. He replied, “This is not the first time, monks, that I have cured him of his grief. I did the same long, long ago.” And with these words he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time, Brahmadatta was the King of Benares. He had two sons. He made the elder son a viceroy (ruler of a province), and he made the younger son the commander-in-chief. When Brahmadatta passed away, the courtiers were in favor of making the elder son King by the ceremonial sprinkling. But the elder son said, “I care nothing for a kingdom. Let my younger brother have it.” They begged and implored him, but he would have none of it. So the younger son was sprinkled to be the King.

The elder son did not even want to be a viceroy or any such thing. They begged him to remain and feed on the fat of the land. “No,” he said, “I want nothing to do in this city,” and so he departed from Benares.

He went off to the frontier where he lived with the family of a rich merchant. There he did manual labor. He worked with his own hands. Eventually the family learned who he was. They would not allow him to work but waited upon him as a prince should be attended.

Now after a time the King’s officers came to that village in order to assess the fields for taxes. The merchant went to the prince and said, “My lord, we support you. Will you send a letter to your younger brother and get us relief from taxation?” He agreed to this. He wrote as follows: “I am living with the family of a merchant. I ask that you forgive their taxes for my sake.” The King consented, and he ordered it to be so.

Accordingly all the villagers and the people of the countryside went to him and said, “If you can get our taxes forgiven, we will pay taxes to you.” For them, too, he sent his petition, and he managed to get their taxes forgiven. And after that the people paid their taxes to him.

His fame, renown, and honor were great. And with this greatness his greed grew as well. So by degrees he asked for control over the whole district, and then he asked for the office of viceroy. The younger brother gave it all to him. Then as his greed kept growing, he was not content even with viceroyalty, and he decided to seize the entire kingdom.

He set out with a host of soldiers. He took up a position outside the city and sent a letter to his younger brother. It said, “Give me the kingdom or fight for it.”

The younger brother thought, “This fool once refused the kingdom and viceroyalty and everything, and now he says that he will take it by force! If I kill him in battle, it will be to my shame. What do I care about being King?” So he sent this message, “I have no wish to fight. You may have the kingdom.” The older brother accepted it and made his younger brother viceroy.

From then on he ruled the kingdom. But he was so greedy that one kingdom was not enough for him. He craved after two kingdoms, then for three, and yet there was no end to his greed.

At that time Sakka, King of the Gods, looked abroad. “Where are they,” he thought, “who carefully tend their parents? Who give alms and do good? Who are seduced by the power of greed?” He saw that this king was subject to greed. “That fool,” he thought, “is not satisfied with being the King of Benares. Well, I will teach him a lesson.”

So Sakka took the form of a young brahmin. He stood at the door of the palace and sent in word that at the door stood a clever young man. He was admitted, and wished victory to the King. Then the King said, “Why have you come?”

“Mighty King!” he answered, “I have something to say to you, but I desire privacy.”

By the power of Sakka, at that very instant all the people disappeared. Then the young man said, “Oh great King! I know three cities. They are prosperous, thronged with men, strong in troops and horses. By my own power I will obtain their lordship and deliver them to you. But you must make no delay and go at once.”

The King, being full of greed, gave his consent. But by Sakka’s power he was prevented from asking, “Who are you? Where did you come from? And what do you want in return?” So Sakka said his piece, and then he returned to the Heaven of the Thirty-three (the Tavatiṃsa heaven).

Then the King summoned his courtiers, and addressed them. “A youth has been here, promising to capture and give me the lordship of three kingdoms! Go, look for him! Send the drum beating about the city. Assemble the army and make no delay, for I am about to take three kingdoms!”

“Oh great King!” they said, “did you offer hospitality to the young man, or did you ask where he lives?”

“No, no, I did not offer him hospitality, and I did not ask where he lives. Go look for him.”

They searched and searched, but they could not find him. They informed the King that they could not find the young man in the whole city. On hearing this the King became depressed. “My lordship over three cities is lost,” he obsessed again and again. “I am deprived of great glory. Doubtless the young man went away angry with me because I did not give him any money for his expenses or a place to live.” Then a burning arose in his body. It was full of greed. As the body burned, his bowels became upset. As the food went in, so it came out. Physicians could not cure him. The King was exhausted. News of his illness was broadcast all through the city.

At that time the Bodhisatta had returned to his parents in Benares from Takkasilā University where he had mastered all the branches of learning. He heard the news about the King. He proceeded to the palace door with the intention to cure him. He sent a message saying that a young man was there to cure the King. The King said, “The best and most renowned physicians, known far and wide, are not able to cure me. What can a young boy do? Give him some money and tell him to go away.”

The young man replied, “I do not want to be paid for my treatment. But I will cure him. Let him simply and only pay me the for the price of my medicine.”

When the King heard this he agreed and admitted him. The young man saluted the King. “Fear nothing, Oh King!” he said. “I will cure you. But first tell me the origin of your disorder.”

The King answered angrily, “What is it to you? Make your medicine.”

“Oh great King,” he said, “it is the way of physicians to first learn from where the disease arises. Then it will be possible to make a remedy to suit.”

“Very well, my son,” the King said, and he proceeded to tell him the origin of the disease. He began from where the young man had come and promised that he would conquer and give to him the lordship over three cities.

“Thus, my son, the disease arose from greed. Now cure it if you can.”

“Well, Oh King!” he said, “can you capture those cities by grieving?”

“Why no, my son.”

“Since that is so, why grieve, Oh great King? Everything, animate or inanimate, must pass away and leave everything behind, even its own body. Even if you should obtain rule over four cities, you could not at one time eat four plates of food, recline on four couches, or wear four sets of robes. You ought not to be the slave of desire, for desire, when it increases, allows no release from the four states of suffering.”

(Presumably these are the four realms of suffering: hell, animal, hungry ghost, and the Asuras.)

Thus having admonished him, the Great Being declared the Dhamma in the following stanzas:

“He that desires a thing, and then this his desire fulfilment blesses,

Sure a glad-hearted man is he, because his wish he now possesses.

He that desires a thing, and then this his desire fulfilment blesses,

Desires throng on him more and more, as thirst in time of heat oppresses.

As in the horned cow, the horn with their growth larger grows,

So, in a foolish undiscerning man, that nothing knows,

While grows the man, the more and more thirst grows, and craving grows

Give all the rice and grain on earth, slave-men, and cow, and horse,

‘Tis not enough for one, know this, and keep a righteous course.

A king that should subdue the whole world wide,

The whole wide world up to the ocean bound,

With this side of the sea unsatisfied

Would crave what might beyond the sea be found.

Brood on desires within the heart - content will never arise.

Who turns from these, and the true cure descries,

He is content, whom wisdom satisfies.

Best to be full of wisdom, these no lust can set afire,

Never the man with wisdom filled is slave unto desire.

Crush your desires, and want little, not greedy all to win,

He that is like the sea is not burnt by desire within,

But like a cobbler, cuts the shoe according to the skin.

For each desire that is let go a happiness is won,

He that all happiness would have, must with all lust have done.”

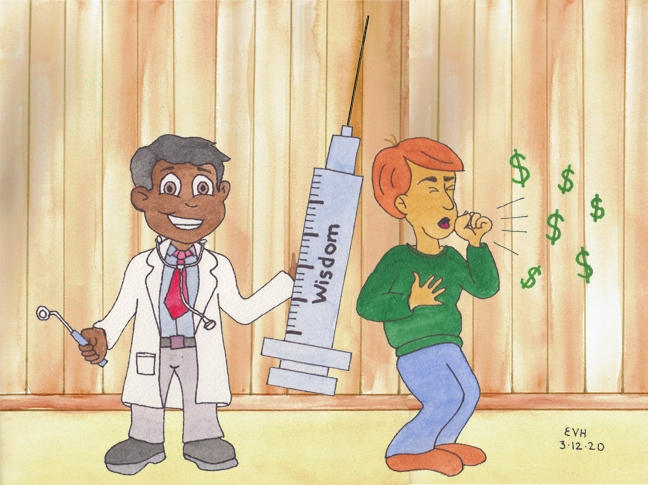

Figure: The Cure for the Sickness of Greed

But as the Bodhisatta was repeating these stanzas, his mind being concentrated on the King’s white umbrella (the symbol of royal power), there arose in him the mystic rapture attained through white light (the bright white light obtained through meditation, i.e., the white “kasina”). The King for his part became whole and well. He arose from his seat in joy. “When all those physicians could not heal me, a wise youth has made me whole by the medicine of his wisdom!” And he then repeated the tenth stanza:

“Eight verses have you uttered, worth a thousand pieces each,

Take, Oh great brahmin! Take the sum, for sweet is this your speech.”

(There are eight stanzas starting with the second that describe the eight causes of misery due to greed.)

At which the Great Being repeated the eleventh stanza:

“For thousands, hundreds, million times a million, nothing cared I,

As the last verse I uttered, in my heart desire did die.”

Increasingly delighted, the King recited the last stanza in praise of the Great Being:

“Wise and good is indeed this youth, all the lore of all worlds knowing,

All desire in very truth is mother of misery by his showing.”

“Great King!” the Bodhisatta said, "be mindful and walk in righteousness.”

Thus admonishing the King, he passed through the air to the Himalaya Mountains. There he lived the life of a recluse while life lasted. He cultivated the Excellences (the brahma vihāras) and became destined for rebirth in the world of Brahma.

This discourse ended, the Master said, “Thus, monks, in former days as now, I made this brahmin whole.” So saying, he identified the birth: “At that time this brahmin was the King, and I was the wise young man.”