Jataka 149

Ekapaṇṇa Jātaka

The Single Leaf

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a lovely story with a lovely metaphor. In the main story, the Bodhisatta uses the example of a single, poisonous leaf to show a wicked prince the error of his ways.

Some people object to folk stories and myths as being “lies.” But as Joseph Campbell said, myths are metaphors. And the lessons you learn from stories like this are much more likely to leave an impact that simply being told to do something.

Some people object to the notion that doing evils results in being reborn in hell. This is from our Judeo-Christian heritage which uses hell as a bludgeon. It is a fine line, but Buddhists have a similar notion but with an important difference. There is no God who issues punishment. Instead it is the simple consequences of our actions that determines our future. If we are kind and wise, we are likely to be happy in the future and to have a good rebirth. The converse is also true.

“If poison lurks.” This story was told by the Master when he was living in the gabled house in the great forest near Vesālī in the kingdom of Licchavi. It is about Prince Wicked.

In those days Vesālī enjoyed marvelous prosperity. A triple wall encompassed the city. Each wall was 5 kilometers from the next one. There were three gates with watch-towers. In that city there were 7,707 kings to govern the kingdom and an equal number of viceroys, generals, and treasurers.

Among the kings’ sons was one known as Wicked Licchavi Prince. He was a fierce, passionate, and cruel young man. He was always punishing people like an enraged viper. He had such a passionate nature that no one could say more than two or three words in his presence. Not his parents, family, or friends could control him.

So at last his parents decided to bring the uncontrollable youth to the All-Wise Buddha realizing that he was the only one who could possibly tame their son’s fierce spirit. So they brought him to the Master, whom, with due respect, they asked to teach the youth a lesson.

Then the Master addressed the prince and said, “Prince, human beings should not be passionate or cruel or ferocious. The fierce man is one who is harsh and unkind alike to the mother that bore him, to his father and child, to his brothers and sisters, and to his wife, friends and family. He inspires fear like a viper darting forward to bite, like a robber springing on his victim in the forest, like an ogre attacking. The fierce man will be reborn after this life in hell or another place of punishment. Even in this life, no matter how magnificently he is adorned, he will look ugly. Even if his face is as beautiful as the circle of the full moon, it is like a lotus that is scorched by flames or a disc of gold covered with filth. It is such rage that drives men to kill themselves with the sword, to take poison, to hang themselves, and to throw themselves from high cliffs. And so it comes to pass that, meeting their death by reason of their own rage, they are reborn into torment. So too they who hurt others are hated even in this life, and because of their evil when the body dies they pass into hell and punishment. Once more they are born as men, disease and sickness of eye and ear and of every kind will beset them from their birth onward. Therefore, let all men show kindness and be doers of good, and then most assuredly hell and punishment hold no fear for them.”

This one lecture had such power on the prince that his pride was humbled immediately. His arrogance and selfishness passed from him and his heart turned to kindness and love. Never again did he abuse or strike, and he became gentle as a snake with drawn fangs, like a crab with broken claws, as a bull with broken horns.

Seeing this change of mood, the monks talked together in the Dharma Hall about how the Licchavi Prince Wicked, whom the ceaseless pleading of his parents could not control, had been subdued and humbled with a single exhortation by the All-Wise Buddha, and how this was like taming six rutting elephants at once. It has been well-said that, “The elephant-tamer, monks, guides the elephant he is breaking in, making it to go to right or left, backward or forward, according to his will. In the same way the animal-tamer trains horses and oxen. So too the Blessed One, the All-wise Buddha, guides the man he would train, guides who he wills along any of the eight directions, and makes his pupil to see what is outside himself. Such is the Buddha and he alone is hailed as chief of the trainers of men, supreme in bowing men to the yoke of Dharma. For, sirs," said the monks, “there is no trainer of men like the Supreme Buddha.”

Just then the Master entered the Dharma Hall and asked what they were discussing. Then they told him and he said, “Monks, this is not the first time that a single exhortation of mine has conquered the prince. This has happened before.”

And so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born as a brahmin in the North country. When he grew up he first learned the Three Vedas and all learning at Takkasilā University. And for a while he lived a worldly life.

But when his parents died he became a recluse, living in the Himalayas. He attained the mystic Attainments (the jhānas) and Knowledges (the power of faith, the power of moral shame, the power of moral dread, the power of energy, and the power of wisdom). There he lived for a long time, until the need of salt and other necessities brought him back to the paths of men. He went to Benares where he took up his residence in the royal pleasure garden.

On the next day he dressed himself with care, and in the best garb of an ascetic went in search for alms in the city. He came to the King’s gate. The King was sitting down and saw the Bodhisatta from the window. He noticed how the hermit, wise in heart and soul, fixing his gaze immediately before him, moved in lion-like majesty. It was as if at every footstep he was giving the gift of a thousand gold pieces. “If goodness lives anywhere,” the King thought, “it must be in this man’s heart.”

So he summoned a courtier. He told him to bring the recluse into his presence. The courtier went up to the Bodhisatta and with due respect, took his alms bowl from his hand. “What do you want, your excellency?” the Bodhisatta said. “The King requests the pleasure of your company,” replied the courtier. “My home,” the Bodhisatta said, “is in the Himalayas, and I do not have the King’s favor.”

So the courtier went back and reported this to the King. Thinking that he had no confidential adviser at the time, the King asked that the Bodhisatta be brought to him, and the Bodhisatta finally agreed.

The King greeted him with great courtesy. He asked him to sit on a golden throne underneath the royal parasol. And the Bodhisatta was fed on great delicacies that had been made for the King himself.

Then the King asked where the recluse lived and learned that his home was in the Himalayas.

“And where are you going now?”

“In search, sire, of a place to stay for the rainy season.”

“Why not live in my pleasure garden?” the King suggested. The Bodhisatta consented, and having eaten himself, the King went to the pleasure garden with his guest. There he had a hermitage built with one room for the day and one room for the night. This dwelling was provided with the eight requisites of an ascetic. (The eight requisites are 1) an outer robe, 2) an inner robe, 3) a thick double robe for winter, 4) an alms bowl, 5) a razor, 6) a needle and thread, 7) a belt and 8) a water strainer.)

Having established the Bodhisatta, the King put him under the protection of the gardener and went back to the palace. This is how it came to pass that the Bodhisatta lived from then on in the King’s pleasure garden, and two or three times every day the King would go to visit him.

Now the King had a fierce and passionate son who was known as Prince Wicked. He was beyond the control of his father and family. Councilors, brahmins, and citizens all pointed out to the young man the error of his ways, but these efforts were all in vain. He did not pay any attention to any of them. The King felt that the only hope of reclaiming his son lay with the virtuous recluse. So as a last resort he took the prince and handed him over to the Bodhisatta to deal with.

The Bodhisatta walked with the prince in the pleasure garden until they came to where a seedling Nimb tree (an Indian lilac) was growing. On the tree there were only two leaves. One was growing on one side, and one was growing on the other side.

“Taste a leaf of this little tree, prince,” the Bodhisatta said, “and see what it is like.”

The young man did so, but he had barely put the leaf in his mouth when he spit it out with a curse, and he coughed and spit to get the taste out of his mouth.

“What is the matter, prince?” the Bodhisatta asked.

"Sir, today this tree only has a little deadly poison. But if it is left to grow, it will prove to be the death of many people,” the prince said. And with that he pulled up the tiny growth and crushed it in his hands, reciting these lines:

If poison lurks in the baby tree,

What will the full growth prove to be?

Then the Bodhisatta said to him, “Prince, dreading what the poisonous seedling might become, you have torn it up and ripped it to pieces. Even as you acted to the tree, so the people of this kingdom, dreading what a prince so fierce and passionate may become when King, will not place you on the throne. They will uproot you like this Nimb tree. They will drive you into exile. Therefore, take warning from this tree. From here on show mercy and abound in loving-kindness.”

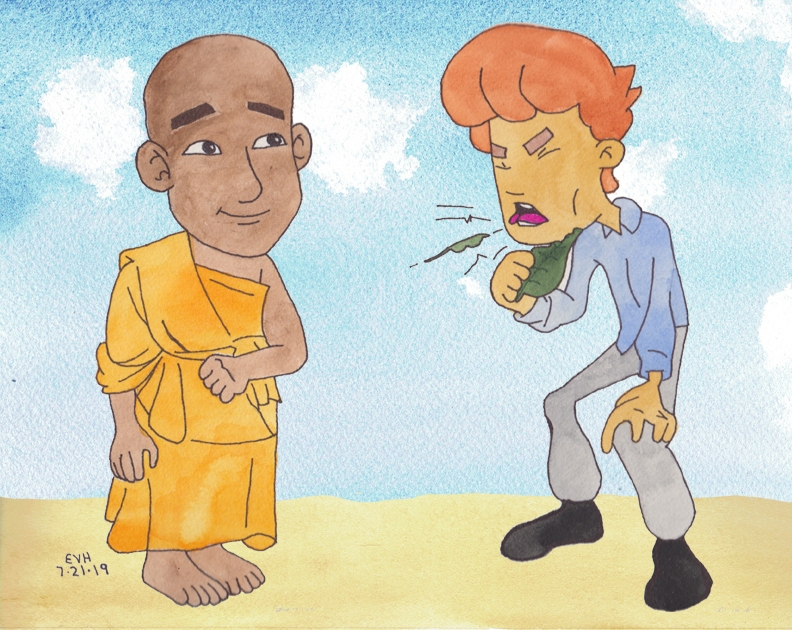

Figure: The Bitter Taste of Bad Behavior

From that time on the prince’s mood changed. He grew humble and meek, merciful, and overflowing with kindness. Abiding by the Bodhisatta’s counsel, when he became King at his father’s death, he abounded in charity and other good works, and in the end he passed away to fare according to his karma.

His lesson ended, the Master said, “So, monks, this is not the first time that I have taught Prince Wicked. I did the same in days gone by.” Then he identified the birth by saying, “The Licchavi Prince Wicked of today was the Prince Wicked of the story. Ānanda was the King, and I was the recluse who exhorted the prince to goodness.”