Jataka 18

Matakabhatta Jātaka

The Goat That Laughed and Cried

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

Animal sacrifice was common during the Buddha’s time. This story is about the karmic consequences of killing. This teaching was so powerful that when India became a predominately Buddhist country in the first millennium, it also became a largely vegetarian country. This is true to this day.

“If people only knew.” This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana. It is about Feasts for the Dead. For at this time people were killing goats, sheep, and other animals, and offering them up as a Feast for the Dead. They believed that this would benefit their dead relatives. Seeing what they were doing, the monks asked the Master, “Just now, sir, people are sacrificing many living creatures and offering them up as a Feast for the Dead. Can it be, sir, that there is any good in this?”

“No, monks,” replied the Master. “No good arises when life is taken with the object of providing a Feast for the Dead. In bygone days wise people, preaching the Dharma from mid-air, showed the evil consequences of the practice. They made the whole continent renounce it. But now, when their previous existences have become confused in their minds, the practice has begun again.” And, so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, there was a brahmin who was well-versed in the Three Vedas. He was world-renowned as a teacher. He decided to offer a Feast for the Dead, so he obtained a goat and said to his pupils, “My sons, take this goat down to the river and bathe it. Then hang a garland round its neck, give it a pot of grain to eat, groom it, and bring it back.”

“Very good,” they said, and down to the river they took the goat. There they bathed and groomed the creature and set it on the bank. The goat, becoming conscious of the deeds of its past lives, was overjoyed at the thought that on this very day it would be freed from all its misery, and he laughed out loud. But then he thought that by killing him the brahmin would bear the misery of that misdeed. The goat felt a great compassion for the brahmin and began to cry. “Friend goat,” said the young brahmins, “your voice has been loud both in laughter and in weeping. What made you laugh and what made you cry?”

“Ask me that question in front your master.”

So they took the goat to their master and told him what happened. After hearing their story, the master asked the goat why it laughed and why it cried. Whereupon the animal, recalling its past deeds by its power to remember its former existences, said to the brahmin, “In the past, brahmin, I, like you, was a brahmin versed in the mystic texts of the Vedas. I, too, offered a Feast for the Dead, killing a goat for my offering. Because I killed that single goat, I have had my head cut off 500 times in 500 lives. This is my 500th and last birth to repay that debt. I laughed out loud when I thought that today I will finally be free from my misery. But then I cried when I thought how today I will be freed from my misery, but you, as a penalty for killing me, would be doomed to lose your head, like me, 500 times. It was out of compassion for you that I cried.”

“Do not be afraid, goat,” said the brahmin. “I will not kill you.”

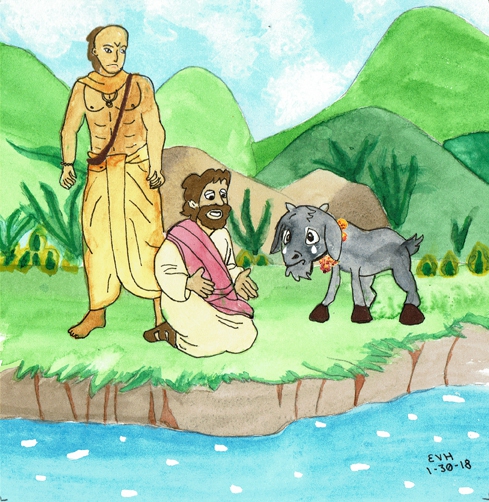

Figure: The Compassionate Goat

“What do you say, brahmin?” said the goat. “Whether you kill me or not, I cannot escape death today.”

“Fear not, goat. I will protect you.”

“Your protection is weak, brahmin, and the power of my evil conduct is strong.”

Setting the goat free, the brahmin said to his disciples, “Let us not allow anyone to kill this goat.” And, accompanied by the young men, he stayed close to the animal. The moment the goat was set free, it reached out its neck to browse on the leaves of a bush growing near the top of a rock. At that very instant a thunderbolt struck the rock, shooting off pieces of rock that hit the goat on the outstretched neck and tore off its head. And people came and crowded around the dead goat.

In those days the Bodhisatta had been born a tree fairy in that same place. By his supernatural powers he now seated himself cross-legged in mid-air while all the crowd looked on. He thought to himself. “If these creatures only knew the results of this type if evil conduct, perhaps they would stop killing.” In his sweet voice he taught them the Dharma in this stanza:

If people but knew the penalty would be

Birth into sorrow, living things would stop

From taking life. Harsh is the killer’s burden.

Thus did the Great Being preach the Dharma, scaring his hearers with the fear of hell. And the people, hearing him, were so terrified at the fear of hell that they stopped taking life. And the Bodhisatta, after teaching them in the Precepts and preaching the Dharma to them, passed away to fare according to his karma. The people, too, remained steadfast in the teaching of the Bodhisatta and spent their lives in charity and other good works, so that in the end they went the City of the Devas (the heavenly realms).

His lesson ended, the Master showed the connection, and identified the birth by saying, “In those days I was the tree fairy.”