Jataka 31

Kulāvaka Jātaka

On Mercy to Animals

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story in the present has a water strainer as its central object. Monks and nuns at the time of the Buddha were only allowed eight possessions: 1) an outer robe, 2) an inner robe, 3) a thick robe for the winter, 4) an alms bowl for food, 5) a razor for shaving, 6) a needle and thread, 7) a belt, and 8) a water strainer. The water strainer was for removing impurities from the water, but as noted here, it was also to strain out tiny, living creatures so that the monks and nuns would not inadvertently kill them.

This feels to me like somewhat more of a Jain theme than a Buddhist one. The Jain religion is very strict about non-harming. They even wear masks across their faces so they do not accidentally inhale and kill tiny bugs. However it came to be, it is still a lovely example of being considerate and compassionate to all living beings, no matter how tiny they are.

The Jātaka Tale itself is quite long and rambling. It can be divided into four parts. In the first part the Bodhisatta convinces the men of the village to devote their lives to doing good deeds and following the Five Moral Precepts (Not killing, not stealing, refraining from sexual misconduct, not lying, and not using intoxicants.). However, this makes the head of the village angry because he used to make money from their drinking and bad behavior. So he goes to the King and accuses them of being criminals. However, because of their virtue they are able to gain the King’s favor and are given control of the village.

In the second part of the story the Bodhisatta and his men build a great hall at the main intersection in the town. However, they exclude women from their good works. But a woman named “Goodness” conspires with the carpenter to build a pinnacle for the building. After this, two other women also contribute to the building project, and the village grows and prospers.

In the third part, the Bodhisatta is reborn as Sakka, the King of the Devas. He fights a war against the Asuras, who are demigods. In this part of the story, Sakka is fighting the Asuras using his powerful chariot. But because his action is accidentally killing Garuḷas (these are creatures that are half man and half bird) he stops, even though it means he may lose the battle.

In the fourth part of the story we follow the fates of four women, three of whom are the ones who contributed to the village building project. They are reborn in a high heavenly realm because of their generosity. However, a fourth woman has a low rebirth as a crane because she did not do any acts of merit during her life. Sakka finds her and teaches her to keep the Five Precepts, and because of her ensuing virtue ends up as the wife of Sakka.

The idea of merit may sound rather mercenary to a Western audience, but it is a very important theme in Buddhism. One gains merit by good and wholesome acts. They have as their fruit a good rebirth. And of course, the purer and more sincere the act is, the greater the merit. Everybody wins.

“Save all the forest’s children.” This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana. It is about a monk who drank water without straining it.

Tradition says that two young monks who were friends went from Sāvatthi into the country to live in a pleasant spot. After staying there as long as they wanted, they left and set out for Jetavana in order to see the Perfect Buddha.

One of them carried a strainer, but the other one did not have one so both of them used the same strainer before drinking. One day they had an argument. As a result, the owner of the strainer did not let his companion use it, and he strained and drank alone by himself.

Because the other monk was not allowed to use the strainer, he drank water without straining it. Eventually they both reached Jetavana, and after saluting the Master, they took their seats. After greeting the two monks, he asked where they came from.

“Sir,” they said, “we have been living in a town in the Kosala country. We came here to see you.”

“I trust you have arrived as good friends, just as you did when you started?” the Buddha said.

The brother without a strainer said, “Sir, we had an argument on the road, and he would not lend me his strainer.”

The other monk said, “Sir, he didn’t strain his water, but intentionally drank it down with all the living things it contained.”

“Is this true, brother, that you intentionally drank water with all the living things it contained?”

“Yes, sir, I did drink unstrained water,” he replied.

“Brother, in bygone days there were wise and good men who were fleeing an enemy after they had been routed. This was in the days of their sovereignty over the City of the Devas. But they would not kill living creatures even to win the battle. Rather, they turned their chariots back, sacrificing great glory in order to save the lives of the children of the Garuḷas.” And, so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time there was a king of Magadha reigning at Rājagaha. The Bodhisatta was born in those days as a young noble. He was named “Prince Magha,” but when he grew up, he became known as “Magha the young Brahmin.” His parents arranged a marriage for him with a young woman from a family of equal rank. And he, with a family of sons and daughters growing up around him, was very generous and charitable, and he kept the Five Precepts.

There were just thirty families in the village, and one day the men were standing in the middle of the village conducting their affairs. The Bodhisatta cleared aside the dust from where he was standing and was standing there in comfort, when another man came and took his place there. Then the Bodhisatta made himself another comfortable standing place, only to have it taken from him like the first. Again and again the Bodhisatta cleared a space until he had made comfortable standing places for every man there.

On another occasion he put up a pavilion. Later on he pulled it down and built a hall with benches and a jar of water inside. Over time these thirty men were led by the Bodhisatta to become like him. He established them in the Five Precepts, after which they used to go around with him doing good works. They were always in the Bodhisatta’s company. They used to get up early and go out with razors and axes and clubs in their hands. They used to roll all of the stones out of the way that lay on the four highways and other roads of the village. They cut down any trees that would scrape against the axles of chariots. They smoothed out rough places on the roads. They built causeways, dug water tanks, and built a hall. They showed charity and kept the Precepts. In this way the villagers followed the Bodhisatta’s teachings.

The head of the village, however, thought to himself, “When these men used to get drunk and commit crimes, I would make a lot of money by selling them drinks and by the fines they paid. But now here is this young brahmin Magha who is making them keep the Precepts. He is putting a stop to murders and other crime.” And in his rage he cried, “I’ll make them keep the Five Precepts!”

So he went to the King and said, “Sire, there is a band of robbers going about sacking villages and committing other crimes.” When the King heard this, he sent his headman to go and bring the men back to him. They were brought back and presented as prisoners to the King. Without giving them a chance to defend themselves, the King proclaimed that they should be trampled to death by an elephant. They were forced to lie down in the King’s courtyard, and the King sent for the elephant. The Bodhisatta encouraged the men, saying, “Remember the Precepts. Love the slanderer, the King, and the elephant as yourselves.” And so they did.

Then the elephant was brought in to trample them to death. Yet no matter what they did, the elephant would not go near them. Instead he ran away trumpeting loudly. Elephant after elephant was brought up, but they all ran away like the first elephant. Thinking that the men must be using some drug on the elephants, the King ordered them to be searched. They did the search but found nothing, and they reported this to the King. “Then they must be using a spell,” said the King. “Ask them whether they are using a spell.”

The question was put to them, and the Bodhisatta said they, indeed, had a spell. The King’s people told this to his majesty. So the King summoned them to him, and he said, “Tell me your spell.”

The Bodhisatta replied, “Sire, this is our spell. No one among the whole thirty of us destroys life. We do not take what is not freely given. We do not commit any acts of wrongdoing, and we do not lie. We do not use intoxicants to the point of heedlessness. We abound in lovingkindness. We show charity. We level the roads, dig tanks, and we built a public hall. This is our spell, our safeguard, and our strength.”

The King was very pleased with this, and he gave them everything the slanderer owned and made him their slave. He even gave them the elephant and the village.

* * *

After this they were able to do good works to their hearts’ content. They sent for a carpenter and had him build a large hall at the junction of the four highways. But because they had lost all desire for women, they would not let any woman share in the good work.

Now in those days there were four women in the Bodhisatta’s house. Their names were Goodness, Thoughtful, Joy, and Highborn. Goodness, finding herself alone with the carpenter, bribed him, saying, “Brother, please help make me the main benefactor of this hall.”

“Very well,” he said. And before doing any other work on the building, he had some of his finest wood dried. He made it into a pinnacle for the building. He wrapped it up in cloth and laid it aside. When the hall was finished and it was time to put on the pinnacle, he exclaimed, “Alas, my masters, there’s one thing we have not made.”

“What is that?”

“Why, we ought to have a pinnacle.”

“All right, let’s get one.”

“But it can’t be made out of green wood. We need a pinnacle made from wood that was cut some time ago, and then fashioned and bored and set aside.”

“Well, what can we do now?”

“Why, let me look around and see if anybody has a pinnacle on his house that might be for sale.” As they looked around, they found one in the house of Goodness. But she would not sell it to them. “If you will make me a partner in the good work,” she said, “I will give it you for nothing.”

“No,” they replied, “we do not let women share in our good work.”

Then the carpenter said to them, “My masters, why do you say this? There is no place from which women are excluded. Take the pinnacle, and our work will be complete.”

So they agreed. They took the pinnacle and completed their hall. They had benches installed. They put jars of water inside and provided a constant supply of boiled rice. They built a wall around the hall with a gate. They put sand inside the wall and planted a row of palm trees. The lady Thoughtful planted a pleasure garden there, and she planted every variety of flowering or fruit-bearing tree. Joy had a water tank dug there, and she covered it with the five kinds of lotuses. It was beautiful to behold. However, the lady Highborn did nothing.

The Bodhisatta fulfilled these seven mandates: to cherish one’s mother, to cherish one’s father, to honor one’s elders, to speak the truth, to avoid harsh speech, to avoid slander, and to be generous.

Whoever supports his parents, honors age,

Is gentle, friendly, does not slander,

Is generous, truthful, and is not harsh,

Even the Thirty-Three shall hail him as Good.

(The Thirty-Three is one of the heavenly realms in the Buddhist cosmology. It is called that because it is ruled by 33 devas, or gods.)

The town grew to be highly renowned, and when he died the Bodhisatta was reborn in the Realm of the Thirty-Three as Sakka, King of Devas. His friends were also reborn there.

* * *

In those days there were Asuras (demigods) living in the Realm of the Thirty-Three. Sakka, King of Devas, said “What good is a kingdom for us that we have to share? So he got the Asuras drunk and threw them by their feet onto the slopes of Mount Sineru. (Mount Sineru is the sacred five-peaked mountain that is the center of the spiritual universe.) They tumbled back down to “The Asura Realm,” as it is called. This is a region on the lowest level of Mount Sineru. It is equal in size to the Realm of the Thirty-Three. There is a tree there that resembles the Coral Tree of the Devas that lasts for an aeon. It is called the Pied Trumpet-flower. (The Coral Tree of the Devas lasts one kalpa, as stated here. A kalpa is a life of the universe, i.e., the big bang, followed by expansion and then contraction of the universe.) However, they could tell by the blossoms of this tree that this was not the Realm of Devas where the Coral Tree blooms. So they cried, “Old Sakka got us drunk and threw us into the great deep, throwing us out of our heavenly city.”

“Come,” they shouted. “Let us win back our realm from him by force of arms.” And they climbed up the sides of Sineru like ants up a pillar.

Hearing that the Asuras were coming, Sakka went out into the great deep to fight them, but he was driven back. He turned and ran away along crest after crest of the southern deep in his “Chariot of Victory,” which was over 500 miles long.

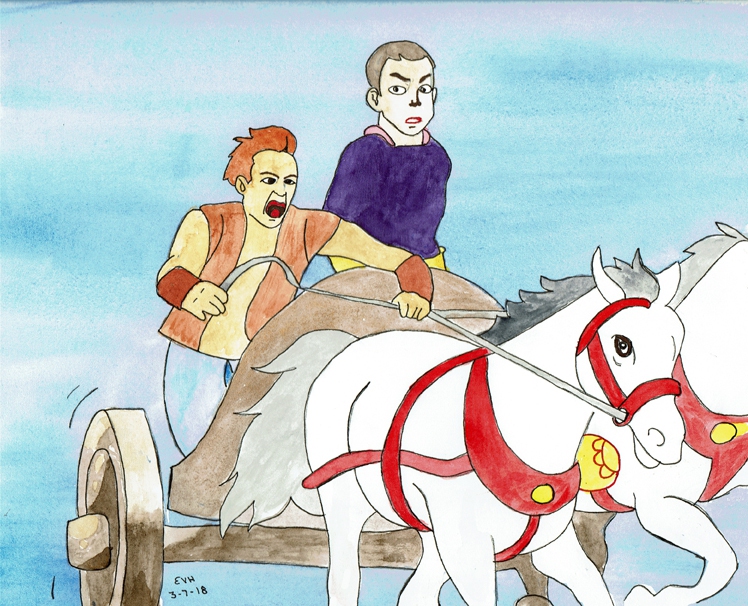

Now as his chariot sped along the deep, it came to the Forest of the Silk-Cotton Trees. As the chariot flew by, these mighty trees were mowed down like so many palms, and they fell into the deep. And as the children of the Garuḷas were in the deep, you could hear their cries. Sakka said to Mātali, his charioteer, “Mātali, my friend, what is that noise? It sounds heartrending.”

“Sire, it is the cry of Garuḷas’ children in their fear. Their forest is being destroyed by the rush of your chariot.”

Sakka said, “Do not let them be afraid because of me, friend Mātali. Let us not, for the sake of conquest, destroy life. Rather I will, for their sake, give my life as a sacrifice to the Asuras. Turn the chariot back.”

And so saying, he repeated this stanza:

Let the forest’s children, Mātali,

Escape our all-devouring chariot.

I offer up, a willing sacrifice,

My life to the Asuras. These poor birds

Shall not, through me, be torn from their nests.

Figure: Sakka Hears the Cries of the Garuḷas’ Children

Mātali, the charioteer, turned the chariot around and went to the Realm of Devas by a different route. But the moment the Asuras saw him turn his chariot round, they cried out that the Sakkas of other worlds must surely be coming up. “It must be his reinforcements that make him turn his chariot around.” Trembling for their lives, they all ran away and never stopped until they were back in the Asura Realm. And Sakka, entering heaven, stood in the midst of his city surrounded by his devas and of Brahma’s angels. And at that moment through a tear in the earth a Victory Palace 3,500 miles high arose. Then, to prevent the Asuras from coming back again, Sakka sent guards in five places, about which it was said:

Both cities are impregnable!

The five guards watch Nāgas, Garuḷas,

Gandhabba, Kumbaṇḍhas, and the Four Great Kings!

(The Nāgas are half man, half serpent. The Gandhabbas are beings in the lowest heavenly realm. Kumbaṇḍhas are goblins. All three of these types of beings live in the Realm of the Four Heavenly Kings, which is just above the human realm. In the Buddhist cosmology, it is the lowest of the heavenly realms.)

* * *

But when Sakka was enjoying the glory of heaven as the King of Devas, safely protected by the guards at these five posts, Goodness died and was reborn as his handmaiden. Because of her gift of the pinnacle, a mansion sprang up for her. It was named “Goodness.” It was studded with heavenly jewels 1,500 miles high. Sakka sat under the white heavenly canopy of royal state, the King of Devas, ruling men and Devas.

The lady Thoughtful, too, died. She was also reborn as a handmaiden of Sakka. The effect of her building the pleasure garden was that there arose a pleasure garden called “Thoughtful’s Vine Grove.” The lady Joy, too, died, and she was likewise reborn as one of Sakka’s handmaidens. The fruit of her water tank was that there arose a tank called “Joy” that was named after her. But Highborn, who had not performed any acts of merit, was reborn as a crane in a cave in the forest.

“There’s no sign of Highborn,” Sakka said to himself. “I wonder where she was reborn.” And as he was thinking about it, he found her. So he paid her a visit and brought her back with him to heaven. He showed her the delightful city of the Devas, the Hall of Goodness, Thoughtful’s Vine Grove, and the tank called Joy. “These three,” Sakka said, “have been reborn as my handmaidens because of the good works they did. But you, having done no good work, were reborn in bad circumstances. From now on you should keep the Precepts.” And having encouraged her in this way and established her in the Five Precepts, he took her back and let her go free. And from then on, she did keep the Precepts.

A short time afterwards, being curious as to whether she was able to keep the Precepts, Sakka went and lay down in front of her in the shape of a fish. Thinking the fish was dead, the crane seized it by the head. The fish wagged its tail. “Why, I do believe it’s alive,” the crane said, and she let the fish go. “Very good, very good,” Sakka said. “You will be able to keep the Precepts.” And so saying he went away.

When she died as a crane, Highborn was reborn into the family of a potter in Benares. Wondering where she had gone, he was able to find where she was. Sakka disguised himself as an old man. He filled a cart with cucumbers of solid gold and sat in the middle of the village. He cried out, “Buy my cucumbers! Buy my cucumbers!” People came to him and asked for them. “I only give them to people who keep the Precepts,” he said. “Do you keep them?”

“We don’t know what you mean by your ‘Precepts.’ Sell us the cucumbers.”

“No. I don’t want money for my cucumbers. I give them away but only to those who keep the Precepts.”

“Who is this clown?” the people said as they turned away. Hearing this, Highborn thought to herself that the cucumbers must have been brought for her, and she went and asked for some. “Do you keep the Precepts, madam?” he said. “Yes, I do,” she replied.

“I brought these here for you and you alone,” he said, and he left the cucumbers, the cart, and everything at her door.

Highborn continued to keep the Precepts for her entire life. After she died she was reborn as the daughter of the Asura King Vepacittiya, and she was rewarded for her goodness with the gift of great beauty. When she grew up, her father gathered the Asuras together and give his daughter the choice of any of them for a husband. And Sakka, who had searched and found out where she was, took the shape of an Asura. He came down and said to himself, “If Highborn chooses a husband truly after her own heart, I will be the one she chooses.”

Highborn was dressed and brought to the place of assembly. There she was told to select a husband after her own heart. She looked around and saw Sakka. She was moved by her love for him in a past existence and chose him for her husband. Sakka carried her off to the city of the devas and made her the chief of 25 million dancing girls. And when his life ended, he passed away to fare according to his karma.

His lesson ended, the Master rebuked that monk with these words: “Thus, monks, the wise and good of bygone days when they were rulers of the Devas, even at the sacrifice of their own lives would not kill. And can you, who have taken an oath, drink unstrained water with all the living creatures in it?” And he showed the connection and identified the birth, by saying, “Ānanda was Mātali the charioteer, and I was Sakka.”