Jataka 40

Khadiraṇgāra Jātaka

The Pit of Coals

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story is about the power of deep faith, resolve, and generosity.

There are several things worth knowing. First, according to the Buddhist tradition, the person that we know as the Buddha is one of many Buddhas throughout time. The idea is that a Buddha is born, awakens, and then teaches the Dharma. But eventually the teaching falls into decline and is lost. Eventually another Buddha is born, and the cycle begins again.

A Pacceka Buddha is a Buddha who awakens but decides not to teach the Dharma. Presumably this is because he does not think that anyone will understand it. This may be because of the era and the culture into which he is born.

Anāthapiṇḍika was the Buddha’s foremost lay supporter. He was a banker and a merchant.

It is interesting to see how in the story in the present, the fairy works her way up the various deva (heavenly) realms appealing to the powers at be. But none of them can grant her forgiveness. She has to first earn the right to ask the Buddha and Anāthapiṇḍika for forgiveness.

“I would rather plunge into the pit of coals.” This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana. It is about Anāthapiṇḍika.

Anāthapiṇḍika had spent fifty-four crores (one crore = 100,000 rupees, so 54 crores are 5,400,000 rupees) on the Faith of the Buddha on the Monastery (at Jetavana). Nothing was more important to him than the Three Gems (Buddha, Dharma, and Saṇgha). He used to go to the monastery every day when the Master was at Jetavana to attend the Great Services: at daybreak, after breakfast, and in the evening. There were intermediate services too. But he never went empty-handed for fear that the novice monks and young lay disciples would see that he had not brought anything with him.

When he went in the early morning, he used to take rice with him. After breakfast he brought ghee, butter, honey, molasses, and the like. And in the evening, he brought perfumes, garlands and cloths. He spent so much every day that his expense knew no bounds.

At the same time, many traders borrowed money from him in the amount of eighteen crores (1,800,000 rupees), and the great merchant never called the money in. Furthermore, another eighteen crores of the family property, which were buried in the river bank, were washed out to sea when the bank was swept away by a storm. The money pots rolled down, with fastenings and seals unbroken, to the bottom of the ocean.

There was always enough rice in his house for 500 monks so that the merchant’s house was to the Saṇgha like a water hole where four roads meet. He was like a mother and a father to them. Even the All-Enlightened Buddha used to go to his house and the Eighty Chief Elders, too, and the number of other monks passing in and out was beyond measure.

Now his house was seven stories high, and it had seven portals. There was a fairy who lived over the fourth gateway, and she was not a follower of the Buddha’s teaching. When the All-Enlightened Buddha came into the house, she could not stay in her home on high, but she was required to come down with her children to the ground floor. She had to do the same thing whenever the Eighty Chief Elders or the other Elders came in and out. She thought to herself, “As long as the ascetic Gotama and his disciples keep coming into this house, I can have no peace here. I can’t keep coming downstairs all the time to the ground floor. I must develop a scheme to stop them from coming any more to this house.” So one day, when the business manager had retired to rest, she appeared before him in material form.

“Who is that?” he said.

“It is I,” came the reply, “the fairy who lives over the fourth gateway.”

“What brings you here?”

“You don’t see what the merchant is doing. Disregarding his own future, he is spending all of his money to enrich the ascetic Gotama. He engages in no business. Tell the merchant to attend to his business and to stop the ascetic Gotama and his disciples from coming to the house anymore.”

Then he said, “Foolish Fairy, if the merchant does spend his money, he spends it on the Faith of the Buddha. This leads to liberation. Even if he seizes me by the hair and sells me for a slave, I will say nothing. Go away!”

Another day, she went to the merchant’s oldest son and gave him the same advice. He scoffed at her in the same way. But she did not dare to speak to the merchant on the matter.

Because of his unending generosity and not doing any business, the merchant’s wealth began to disappear and his estate grew smaller and smaller, so that he sank slowly into poverty. His table, his dress, and his bed and food were no longer what they had once been. Yet, in spite of his new circumstances, he continued to take care of the Saṇgha even though he was no longer able to properly feed them.

So one day when he had bowed and taken his seat, the Master said to him, “Householder, are gifts being given at your house?”

“Yes, sir,” he said, “But there’s only a little sour porridge left over from yesterday.”

“Do not be upset, householder, if you can only offer what is unpalatable. If your heart is good, the food that you give to Buddhas, Pacceka Buddhas, (Pacceka means “solitary”) and their disciples, will be good too. And why is this? Because of the greatness of the merit. Someone who makes his heart good cannot give a gift that is not good. This is demonstrated by the following passage:

If the heart has faith, no gift is small

To Buddhas or to their true disciples.

It is said that no service is small

That is paid to Buddhas, lords of great renown.

Mark well the fruit that is rewarded from that poor gift

Of porridge: dried-up, sour, and lacking salt.

Further, he said, “Householder, in giving this unpalatable gift, you are giving to those who have entered on the Noble Eightfold Path. I once stirred up all India by giving a great gift, and in my generosity and faith I poured forth as though I had made one mighty stream from the five great rivers. Yet I had not found anyone who had reached the Three Refuges or kept the Five Precepts. It is hard to find those who are worthy of offerings. Therefore, do not let your heart be troubled by the thought that your gift is unpalatable.”

(A gift made to followers of the Dharma has more merit than gifts given to those who do not follow the Dharma. The Buddha here is referring to a gift that he gave in a previous life to a Buddha even though there were no disciples.)

Now that fairy who had not dared to speak to the merchant in the days of his generosity thought that he was now poor. And so, entering his bedroom at night she appeared before him in material form, standing in mid-air.

“Who’s that?” the merchant said.

“I am the fairy, great merchant, who lives over the fourth gateway.”

“What brings you here?”

“To give you counsel.”

“Proceed, then.”

“Great merchant, you are not thinking about your own future or for your own children. You have spent so much on the Faith of the ascetic Gotama without undertaking new business that you have been impoverished by the ascetic Gotama. But even in your poverty you do not abandon the ascetic Gotama! The monks are in and out of your house this very day just as usual! You cannot ever get back what they have taken. From now on you should not go to the ascetic Gotama and you should not let his disciples set foot inside your house. Do not even turn to look at the ascetic Gotama but attend to your trade and business in order to restore the family fortune.”

Then he said to her, “Was this the counsel you wanted to give me?”

“Yes, it was.”

The merchant, “The mighty Lord of Wisdom has protected me against a hundred, a thousand, even a hundred thousand fairies such as you! My faith is as strong and steadfast as Mount Sineru (Meru)! I have spent my effort on the faith that leads to liberation. Your words are wicked. They are a blow aimed at the Faith of the Buddhas by you, you wicked and impudent witch. I cannot live under the same roof with you. Leave my house and go live somewhere else!” Hearing these words of that devoted man and disciple, she could not stay. She went back to her dwelling, took her children by the hand, and left.

But even though she left, she thought that if she could not find a place to stay somewhere else, she could make her peace with the merchant and return to live in his house. With this in this mind she went to the protector deity of the city and with due salutation stood in front of him. He asked her why she had come, and she said, “My lord, I spoke improperly to Anāthapiṇḍika, and in his anger he threw me out of my home. Take me to him and help us to reconcile so that he will let me live there again.”

“But what did you say to the merchant?”

“I told him not to support the Buddha and the Saṇgha anymore and not to let the ascetic Gotama come to his house any more. This is what I said, my lord.”

“Your words were wicked. It was a blow aimed at the Faith. I will not help you.”

Getting no support from him, she went to the Four Great Regents of the world (The Four Heavenly Kings, one for each direction). And being rebuffed by them in the same way, she went on to Sakka, King of Devas. She told him her story, begging him still more earnestly: “Deva, finding no shelter, I wander about homeless, leading my children by the hand. Your majesty, please give me some place to live.”

And he, too, said to her, “You have been wicked. It was a blow aimed at the Conqueror’s Faith. I cannot speak to the merchant on your behalf. But I can tell you one way that the merchant might pardon you.”

“Please tell me, deva.”

“Men have borrowed eighteen crores from the merchant. Take his business agent, and without telling anybody go to their houses in the company of some young goblins. Stand in the middle of their houses with the promissory note in one hand and a receipt in the other and terrify them with your goblin power, saying, ‘Here’s an acknowledgment of the debt. Our merchant did not try to collect this debt while he was affluent. But now he is poor, and you must pay the money you owe.’ By your goblin power collect all eighteen crores of gold and fill the merchant’s empty treasuries. He had another treasure buried in the banks of the river Aciravatī, but when the bank was washed away, the treasure was swept into the sea. Get that back also by using your supernatural power and store it in his treasury. Further, there is another sum of eighteen crores lying unowned in such and such a place. Bring that too and pour the money into his empty treasury. When you have atoned for your wickedness by the recovery of these fifty-four crores, ask the merchant to forgive you.”

Figure: Past Due Notice

“Very good, deva,” she said. And she set to work obediently and did just as she had been told. When she had recovered all the money, she went into the merchant’s bedroom at night and appeared before him in material form standing in the air.

The merchant asked who was there. She replied, “It is I, great merchant, the blind and foolish fairy who lived over your fourth gateway. In the stupidity of my folly I did not understand the virtue of a Buddha, and so I came to say what I said to you a few days ago. Please forgive my fault! At the direction of Sakka, King of Devas, I have atoned by recovering the eighteen crores owing to you, the eighteen crores that had been washed down into the sea, and another eighteen crores that were lying unowned in such and such a place. This makes fifty-four crores in all, which I have put into your empty treasury. The sum you spent on the Monastery at Jetavana is now made up again. While I have nowhere to live, I am in misery. Please forgive my foolishness, great merchant, and pardon me.”

Anāthapiṇḍika, hearing what she said, thought to himself, “She is a fairy, and she says she has atoned, and she confesses her fault. The Master will consider this and make his virtues known to her. I will take her before the All-Enlightened Buddha.” So he said, “My good fairy, if you want me to pardon you, ask me in the presence of the master.”

“Very good,” she said, “I will. Take me along with you to the Master.”

“Certainly,” he said. And early in the morning, when night was just passing away, he took her with him to the Master and told the Blessed One all that she had done.

Hearing this, the Master said, “You see, householder, how the fool regards wickedness as excellent before it ripens to fruit. But when it does ripen, then he sees the wickedness to be wicked. Likewise, the good man looks on his goodness as unwholesome before it ripens to fruit. But when it ripens, he sees it to be goodness.” And so saying, he repeated these two stanzas from the Dhammapada:

The fool thinks his wicked deed is good

As long as the wickedness has not ripened into fruit.

But when the wickedness at last ripens,

The fool sees “It was wicked what I did.”

The good man thinks his goodness is unwholesome

As long as it has not ripened into fruit.

But when his goodness begins to ripen,

The good man surely sees “It was good that I did.”

At the close of these stanzas that fairy was established in the Fruit of the First Path (stream-entry). She fell at the wheel-marked feet (tradition holds that a Buddha has a Dharma wheel on the bottom of each foot) of the Master, crying, “Blinded by passion, depraved by unskillfulness, misled by delusion, and blinded by ignorance, I spoke foolishly because I did not know your virtue. Please forgive me!” Then she was pardoned by the Master and the great merchant.

At this time Anāthapiṇḍika sang his own praises in the Master’s presence, saying, “Sir, though this fairy did her best to stop me from giving support to the Buddha and his following, she did not succeed. And though she tried to stop me from giving gifts, I still gave them! Was this not goodness on my part?”

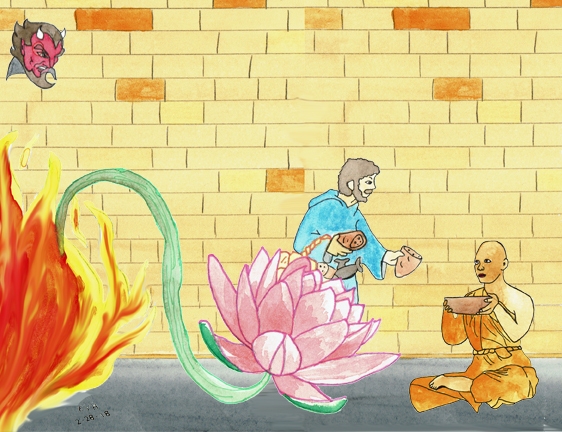

The Master said, “You, householder, are a converted man and a good disciple. Your faith is firm and your vision is purified. It is not surprising that you were not stopped by this impotent fairy. The marvel was that the wise and good of a bygone day, when a Buddha had not appeared and when knowledge had not ripened to its full fruit, should give gifts from the heart of a lotus flower, even though Māra, lord of the Realm of Temptation, appeared in mid-heaven, shouting, ‘If you give gifts, you will roast in hell,’ showing them a pit eighty cubits deep filled with red-hot embers.” And so saying, at the request of Anāthapiṇḍika, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born in the family of the Lord High Treasurer of Benares. He was raised in the lap of luxury like a royal prince. By the time he was sixteen years old, he had made himself perfect in all accomplishments. At his father’s death he filled the office of Lord High Treasurer. He built six alms houses, one at each of the four gates of the city, one in the center of the city, and one at the gate of his own mansion. He was very generous, and he kept the precepts and observed the fasting days.

Now one day at breakfast time when wonderful food was being served to the Bodhisatta, a Pacceka Buddha arose after having been in deep meditation for seven days. Noticing that it was time to go on his alms rounds, he thought that it would be good to visit the Treasurer of Benares that morning. So he cleaned his teeth with a tooth-stick made from a betel vine, washed his mouth with water from Lake Anotatta, put on his inner robe as he stood on the tableland of Manosilā, fastened his outer robe, donned his upper robe, and took his alms bowl. He passed through the air and arrived at the gate of the mansion just as the Bodhisatta’s breakfast was being served.

As soon as the Bodhisatta saw him, he rose from his seat and looked at the attendant, indicating that a service was required. “What would you like me to do, my lord?”

“Bring his reverence’s bowl,” the Bodhisatta said.

At that very instant Māra the Tempter rose up in a state of great excitement, saying, “It has been seven days since the Pacceka Buddha has eaten. If he does not get any food today, he will die. I will destroy him and stop the treasurer from giving anything.”

And that very instant he conjured up a pit of red-hot embers inside the mansion, eighty cubits deep, filled with Acacia charcoal, all ablaze and aflame like the great hell of Avīci (one of the hell realms). When he had created this pit, Māra himself took his position in mid-air.

When the man who was on his way to fetch the bowl saw this, he was terrified and started back. “What makes you start back, my man?” asked the Bodhisatta.

“My lord,” he answered, “there is a great pit of red-hot embers blazing and flaming in the middle of the house.” And as man after man went to the spot, they were all panic-stricken and ran away as fast as their legs would carry them.

The Bodhisatta thought to himself, “Māra the Tempter must be trying to stop me from giving alms. I have yet to be, however, shaken by a hundred or by a thousand Maras. We will see whose strength is greater, whose might is mightier, mine or Māra’s.” So taking a bowl in his hand, he went to the fiery pit and looked up to the heavens. Seeing Māra, he said, “Who are you?”

“I am Māra,” was the answer.

“Did you conjure this pit of red-hot embers?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Why?”

“To stop you from giving alms and to destroy the life of that Pacceka Buddha.”

“I will not permit you to stop me from giving alms or to destroy the life of the Pacceka Buddha. I am going to see today whether your strength or mine is greater.”

And standing on the brink of that fiery pit, he cried, “Reverend Pacceka Buddha, even though I may fall headlong into this pit of red-hot embers, I will not turn back. Only promise to take the food I bring.” And so saying he repeated this stanza:

I would rather plunge headlong

Into this gulf of hell then stoop to shame!

Promise me, sir, to take these alms from my hands!

With these words the Bodhisatta, grasping the bowl of food, strode on undaunted right onto the surface of the pit of fire. But even as he did so, there rose up to the surface through all the eighty cubits of the pit’s depth a large and peerless lotus flower that grasped the feet of the Bodhisatta! And pollen fell from it onto the head of the Great Being, so that his whole body was sprinkled from head to foot with the dust of gold! Standing right in the heart of the lotus, he poured the precious food into the bowl of the Pacceka Buddha.

Figure: The Bodhisatta’s Resolve

And when the latter had taken the food and given thanks, he flung his bowl up into the heavens, and right in everyone’s sight he rose into the air and disappeared back to the Himalayas again, forming a track of fantastically shaped clouds in his path.

And Māra, too, defeated and dejected, passed away back to his home.

But the Bodhisatta, still standing in the lotus, taught the Dharma to the people, extolling alms-giving and the precepts, after which, surrounded by the escorting multitude, he went back into his mansion once more. And all his life he showed charity and did other good works until he passed away to fare according to his karma.

Said the Master, “It was no marvel, layman, that you, with your discernment of the Dharma, were not overcome by the fairy. The real marvel was what the wise and good did in bygone days.” His lesson ended, the Master showed the connection and identified the birth by saying, “The Pacceka Buddha of those days passed away, never to be born again. I was the Treasurer of Benares who, defeating Māra and standing in the heart of the lotus, placed alms in the bowl of the Pacceka Buddha.”