Jataka 56

Kañcānakkhandha Jātaka

The Gold Aggregates

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

There are two principles described in this story. The first is the ability to take something complicated and synthesize it into something that is simpler and more understandable. This is often easier said than done. You have to work really hard at a complex problem in order to understand it enough that it becomes simple. Steve Jobs said, “Simple can be harder than complex: You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple.” This is one reason that I encourage people to read and re-read and re-read the Buddha’s discourses, so you can get to a point where his teachings become clear and simple.

The other principle is called “divide and conquer.” This is also a problem-solving method. You take a problem with a lot of complexity, and you break it down into smaller problems. This is what I believe the simile of the gold is. You take something big and break it into pieces that are more manageable.

Speaking of gold, here is a little fun fact. When gold was first being mined in the American West, there was a big problem with theft. It was much easier to steal gold than it was to mine it. The solution was to put the gold into the big bars of gold bullion that are now so famous. The bars were too big to carry away on horseback. You needed a wagon. This made stealing gold much harder.

Also notice how the Buddha decides to divide his new-found wealth. In the Digha Nikāya [DN 31.26] the Buddha also teaches you to divide your wealth into four parts, although the formula is somewhat different. The Buddha never turned money and wealth into something evil. He only counseled that wealth be acquired in an ethical way and that it be managed wisely and used skillfully.

“When gladness.” This story was told by the Master while at Sāvatthi. It is about a monk. Tradition says that through hearing the Master preach a young gentleman of Sāvatthi gave his heart to the Three Gems (Buddha, Dharma, and Saṇgha), and that he became a monk. His teachers and masters taught him about the Ten Precepts of Morality (these are the precepts taken by a novice monk or nun). They taught him the Short, the Medium, and the Long Moralities (These are described in the Brahmajāla Sutta in the Digha Nikāya sections 1.8-1.27. There are 26 short moralities, 13 medium ones, and 7 long ones.). They set forth the Morality which rests on self-restraint according to the Pātimokkha (the monastic rules), the Morality which rests on self-restraint of the Senses, the Morality which rests on a blameless walk of life, the Morality which relates to the way a monk may use the requisites (food, shelter, clothing, and medicine).

The young novice thought to himself, “There is a lot to this Morality. I will undoubtedly fail to fulfill all that I have vowed. Yet what is the good of being a monk at all, if one cannot keep the rules of Morality? My best course is to go back to the world, take a wife and rear children, living a life of almsgiving and other good works.” So he told his superiors what he thought, saying that he was going to return to the lower state of a layman, and he wished to hand back his bowl and robes.

“Well, if this is what you want,” they said, “at least see the Buddha before you go.” And they brought the young man before the Master in the Dharma Hall.

“Why, monks,” the Master said, “are you bringing this brother to me against his will?”

“Sir, he said that Morality was more than he could observe, and he wants to give back his robes and bowl. So we brought him to you.”

“But why, monks,” the Master asked, “did you burden him with so much? He can do what he can, but no more. Do not make this mistake again. Leave me to decide what should be done in the case.”

Then, turning to the young monk, the Master said, “Come, brother. What concern do you have with Morality? Do you think that you could obey just three moral rules?”

“Oh, yes, Sir.”

“1) Well now, watch and guard the three types of action, those of the voice, the mind, and the body.”

“2) Do no evil in thought, word, or deed.”

“3) Do not stop being a monk.”

“Now go and obey just these three rules.”

“Yes, indeed, Sir, I will keep them,” the glad young man exclaimed, and he went back to his teachers again.

And as he was keeping his three rules, he thought to himself, “I had the whole of Morality told me by my instructors. But because they were not the Buddha, they could not make me grasp even this much. Whereas the All-Enlightened One, by reason of his Buddhahood, and of his being the Lord of Truth, has expressed Morality in only three rules concerning the three types of action, and he has made me understand it clearly. What a great help the Master has been to me.”

And next he won insight (stream entry) and in a few days attained Arahantship. When this came to the ears of the Saṇgha, they discussed it when they met in the Dharma Hall. They talked about how the monk was going to go back to the world because he did not think that he could fulfill Morality. He had been given three rules by the Master that embodied the whole of Morality. He had been made to understand those three rules, and so he had been enabled by the Master to win Arahantship. How marvelous, they cried, was the Buddha.

Entering the Dharma Hall at this point, and learning the subject of their discussion, the Master said, “Monks, even a heavy burden becomes light if taken piecemeal. And thus the wise and good of past times, on finding a huge mass of gold too heavy to lift, first broke it up, and then they were able to carry their treasure away piece by piece.” So saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born as a farmer in a village. One day he was ploughing in a field where there had once been a village. Now, in bygone days, a wealthy merchant had died leaving a huge bar of gold buried in this field. It was as thick as a man’s thigh and six feet long. The Bodhisatta’s plough struck this bar head on and got stuck to it. Thinking it was the root of a tree, he dug it up. Discovering what it really was, he cleaned the dirt off the gold.

At the end of the day at sunset, he put away his plough and gear and tried to pick up his treasure-trove and walk off with it. But when he could not lift it, he sat down next to it and started about thinking how he would spend it.

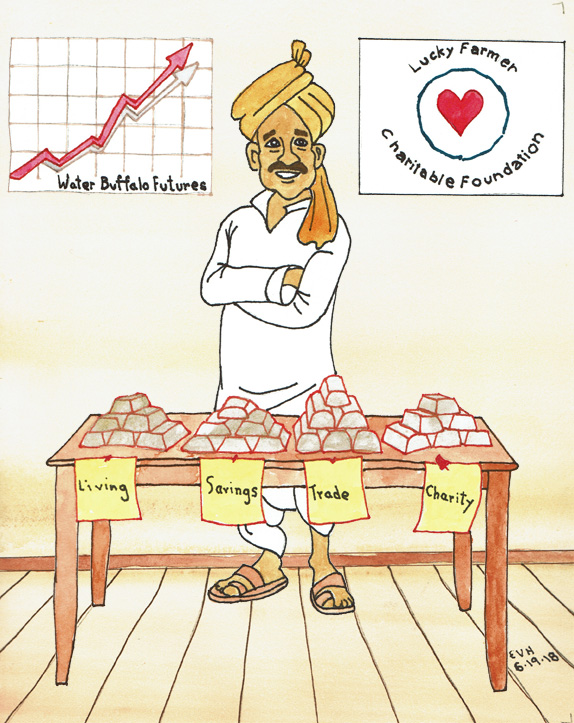

“I’ll have some of it to live on, some I will to bury as a treasure, I will use some for trade, and some of it I will use for charity and good works,” he thought to himself.

This led him to cut the gold into four pieces. Dividing the gold into pieces made it possible to carry it, and he took the lumps of gold home. After a life of charity and other good works, he passed away to fare according to his karma.

Figure: The Happy and Fortunate Farmer

His lesson ended, the Master, as Buddha, recited this stanza:

When gladness fills the heart and fills the mind,

When righteousness is practiced to win peace,

He who so walks shall gain the victory

And all the fetters will be destroyed.

When he had explained awakening up to its crowning point of Arahantship, he showed the connection and identified the birth by saying, “In those days I myself was the man who got the treasure of gold.”