Jataka 61

Asātamanta Jātaka

The Grief Teaching

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

The original version of this story is quite misogynistic. I have modified it to be more in line with the actual teachings of the Buddha.

The university at Takkasilā is mentioned frequently in the Buddhist texts. It was the best university in India at the time.

The word “dolor” is somewhat archaic. It means ”grief” or “sorrow.”

This is a rather incoherent story. First of all, why a Buddhist would aspire to worship a Fire God and be reborn in the Realm of Brahma does not make any sense. And the original version, as noted, is painfully offensive. But buried in here is a story about the dangers of sense desire and the benefits of renunciation.

Finally, note that despite the “issues with mom,” the son treats her with dignity and respect to the last.

“In unbridled passion.” This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana. It is about a lustful monk. The introductory story will be related in the Ummadanti Jātaka (Jātaka 527). The Master said to this monk, “Women, O monk, are objects of lust, and lust is reckless, vile, and degrading. Why let your unbridled passion subject you to such intoxicating feelings?” And so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was reborn as a brahmin in the city of Takkasilā in the Gandhāra country. By the time he had grown up, he was so proficient in the Three Vedas and all accomplishments that his fame as a teacher spread through all the world.

In those days there was a brahmin family in Benares, and they had a son. On the day of his birth they made a fire and kept it burning until the boy was sixteen. Then his parents told him how the fire, started on the day of his birth, had never been allowed to go out, and they told their son to make his choice. If he wanted to gain entrance into the Realm of Brahma, then he should take the fire into the forest. There he could carry work out his aspiration by ceaselessly worshipping the Lord of Fire. But, if he preferred the joys of the home life, they told their son he should go to Takkasilā and study there under the world-renowned teacher so that he could settle down and manage the property.

“I will surely fail in the worship of the Fire God,” the young brahmin said, “so I’ll be a landowner.”

So he said good-bye to his father and mother, and with a thousand pieces of money for the teacher’s fee, he left for Takkasilā. There he studied until his education was complete, after which he headed back home again.

During his time away, his parents increasingly wanted him to forsake the world and to worship the Fire God in the forest. Accordingly, his mother wanted to convince him to go the forest by teaching him about the dangers of sense desire. She was confident that his wise and learned teacher would be able to convince him about the trappings of lust. So she asked him whether he had finished his education.

“Oh yes,” the young man said.

“Then of course you have not omitted the Dolor Texts?”

“I have not learned those, mother.”

“Then how then can you say your education is finished? Go back at once, my son, to your master, and come back to us when you have learned them,” his mother said.

“Very well,” the young man said, and off he went to Takkasilā once more.

Now his master had a mother who was still living. She was an old woman of a hundred and twenty years of age. He used to bathe, feed, and take care of her himself. He was ridiculed by his neighbors for doing this. The ridicule was so extreme that he decided to go to the forest and live there. He built a beautiful hut in the solitude of the forest. Water was plentiful there, and after laying in a stock of ghee and rice and other provisions, he carried his mother to her new home. He lived there respecting her and enjoying her old age.

When the young brahmin got to Takkasilā, he, of course, did not find his master. He asked around and discovered what had happened. So he set out for the forest and presented himself respectfully before his master.

“What brings you back so soon, my boy?” his master said.

“I do not think, sir, I learned the Dolor Texts when I was with you,” the young man said.

“But who told you that you had to learn the Dolor Texts?”

“My mother, master,” he replied.

The Bodhisatta reflected that there were no such texts as those, and he concluded that his pupil’s mother must have wanted her son to learn how destructive sense desire can be. So he said to the youth that it was all right, and that he would in due course learn the texts in question.

“From today,” he said, “you will take my place caring for my mother. You will wash, feed and look after her with your own hands. As you rub her hands, feet, head, and back, be careful to repeat these words, ‘Ah, Madam! if you are so lovely now that you are so old, what must you have been like in the heyday of your youth!’ And as you wash and perfume her hands and feet, burst into praise of their beauty. Further, tell me without shame or reserve every single word my mother says to you. Obey me in this, and you shall master the Dolor Texts. Disobey me, and you will remain ignorant of them forever.”

Obeying his master’s commands, the youth did as he was told. He was so persistent in his praise of the old woman’s beauty that she thought he had fallen in love with her. And even though she was blind and decrepit, passion was kindled within her. So one day she broke in on his compliments by asking, “Do you desire me?”

“I do indeed, madam,” the youth answered, “but my master is so strict.”

“If you desire me,” she said, “kill my son!”

“But how can I, who has learned so much from him, how shall I kill my master for passion’s sake?”

“Well then, if you will be faithful to me, I will kill him myself.”

(So poisonous is the power of lust that even an old woman like this actually thirsted for the blood of such a dutiful son!)

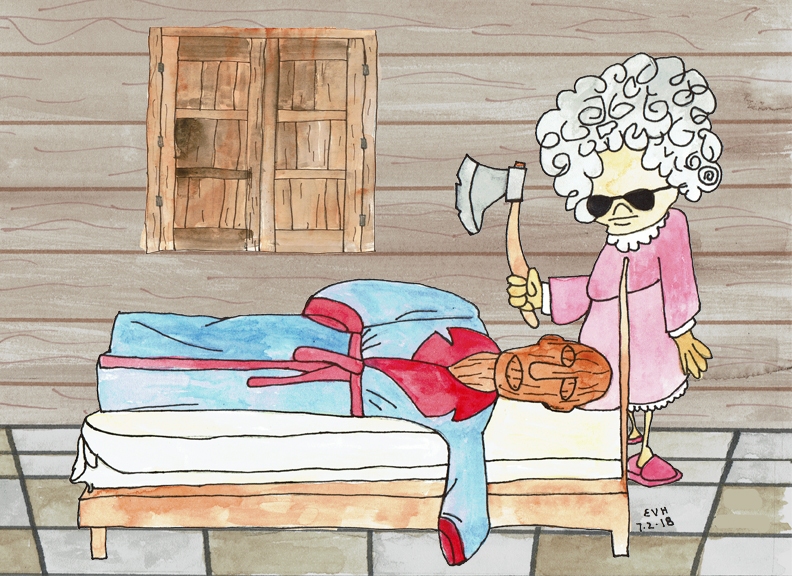

Now the young brahmin told all this to the Bodhisatta, who commended him for reporting the matter. He studied how much longer his mother was destined to live (presumably by astrology). Finding that her destiny was to die that very day, he said, “Come, young brahmin. I will put her to the test.” So he cut down a fig tree and cut a wooden figure out of it that was about his size. He wrapped it up, head and all, in a robe and put it on his bed, tying a string to it. “Now go to my mother, and bring her an axe,” he said. “Give her this string as a way to guide her steps.”

So the youth went to the old woman, and said, “Madam, the master is lying down indoors on his bed. I tied this string as a way to guide you. Take this axe and kill him, if you can.”

“But you won’t abandon me, will you?” she said.

“Why would I?” he replied.

So she took the axe, and, rising up with trembling limbs, groped her way along by the string until she thought she felt her son. Then she bared the head of the figure, and - thinking to kill her son at a single blow - brought the axe down right on the figure’s throat, only to learn by the thud that it was wood!

Figure: Issues With Mom

“What are you doing, mother?” the Bodhisatta said.

With a shriek that she was betrayed, the old woman fell dead to the ground. For, says tradition, it was fated that she should die at that very moment and under her own roof.

Seeing that she was dead, her son cremated her body, and when the flames of the pile were quenched, graced her ashes with wildflowers. Then with the young brahmin he sat at the door of the hut and said, “My son, there is no such passage as the ‘Dolor Text.’ It is lust that is the embodiment of depravity. And when your mother sent you back to me to learn the Dolor Texts, her object was that you should learn how dangerous lust is. You have now witnessed with your own eyes lust’s wickedness, and from that you can see how vile it is.” And with this lesson, he told the youth to leave.

Saying goodbye to his master, the young brahmin went home to his parents. His said mother to him, “Have you now learned the Dolor Texts?”

“Yes, mother.”

“And what,” she asked, “is your final choice? Will you leave the world to worship the Lord of Fire, or will you choose a family life?”

The young brahmin answered, “I have seen the wickedness of lust with my own eyes. I will have nothing to do with family life. I will renounce the world.” And his convictions found expression in this stanza:

In unbridled lust, like devouring fire,

Passion creates an uncontrollable rage.

Without renouncing passion, I would be unable

To find peace in a hermitage.

With this lesson the young brahmin took leave of his parents and renounced the world for the life of a recluse. He was able to find the peace he desired, and so he assured himself entry into the Realm of Brahma.

“So you see, brother,” the Master said, "how vile and woeful lust is.” And after declaring the wickedness of lust, he preached the Four Noble Truths, at the close of which that brother won the Fruit of the First Path (stream entry). The Master then showed the connection and identified the birth by saying,

“Kāpilānī was the mother of those days, Mahākassapa was the father, Ānanda the pupil, and I myself the teacher.”

(The Elder Nun Bhaddā Kāpilānī was a prominent and respected nun who was especially good at recalling her past lives. Why she is depicted as the villain here is unclear. Mahākasspa was an arahant and “foremost in ascetic practices.” He and Kāpilānī were married before they ordained as monastics. Ānanda was, of course, the Buddha’s cousin and his attendant. The Buddha gave him the title “Guardian of the Dharma”.)