Jataka 81

Surāpāna Jātaka

Drinking Alcohol

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story takes place in Kosambī which is one of the more notorious monasteries of the Buddha’s time. There is a famous story that appears several times in the Pāli Canon where there was a conflict between two monks, and when the Buddha tried to intervene, they basically blew him off. The monastery/park in Kosambī was named after Ghosita, who was a devoted lay follower of the Buddha. Ghosita donated the park to the Saṇgha.

In this story we see the Elder Sāgata who has supernormal powers. Yet still he is subject to drunkenness. This shows how even someone who is developed enough to have these powers has still not found peace, liberation, and freedom. This is why supernormal powers do not carry much weight in the Buddha’s Dharma. Many Arahants never developed supernormal powers, yet they were free from unnecessary suffering and the rounds of rebirth.

This story gives the context for the monastic rule against intoxication. In the Vinaya – the monastic code – there is a story for each of the rules. This is so monks and nuns understand not just the rule, but the context and the spirit of the rule. In the early days of the Saṇgha, as the Buddha himself once noted, there was no need for any rules. But as the Saṇgha grew, this became necessary, and rules were added when incidents such as the one described here occurred.

The rule against intoxication is not just in the monastic code, it is a Precept for lay people, as well. This is very unpopular in the West. But the Precept exists not so much because there is anything inherently immoral about intoxication, it is because – as we see in the story – it predisposes us to very unskillful and harmful behavior.

“We drank.” This story was told by the Master about the Elder Sāgata, while he was living in the Ghosita Park near Kosambī.

After spending the rainy season at Sāvatthi, the Master went on an alms pilgrimage to a market town named Bhaddavatikā. There cowherds and goatherds and farmers and wayfarers respectfully advised him not to go down to the Mango Ferry. “For,” they said, “in the Mango Ferry, in the property of the naked ascetics, a poisonous and deadly Naga (a demi-god who is part human and part cobra) lives. He is known as the Naga of the Mango Ferry, and he might harm the Blessed One.”

The Blessed One pretended not to hear them even though they repeated their warning three times, and he continued on his way. While the Blessed One was living near Bhaddavatikā in a certain grove there, the Elder Sāgata, a servant of the Buddha who had won what supernormal powers a human can possess, went to the property of the naked ascetics. There he built a pile of leaves at the spot where the Naga king lived, and he sat down cross-legged on them.

Being unable to conceal his evil nature, the Naga raised a great smoke. So did the Elder. Then the Naga sent forth flames. So too did the Elder. But while the Nāga’s flames did not hurt the Elder, the Elder’s flames did harm the Naga. And so in a short time he conquered the Naga king and established him in the Refuges and the Precepts. Having done this, he went back to the Master. And the Master, after staying as long as it pleased him at Bhaddavatikā, went on to Kosambī.

Now the story of the Nāga’s conversion by Sāgata spread all over the countryside. The townsfolk of Kosambī went out to meet the Blessed One and saluted him, after which they greeted the Elder Sāgata and saluted him, saying, “Tell us, sir, what you need and we will provide it.”

The Elder himself remained silent, but the followers of the Wicked Six (The Wicked Six are mentioned in Jātaka 28. They were notorious monks who were always breaking the monastic rules.) said, “Sirs, to those who have renounced the world, white liquor is very rare. Do you think you could get the Elder some clear white liquor?”

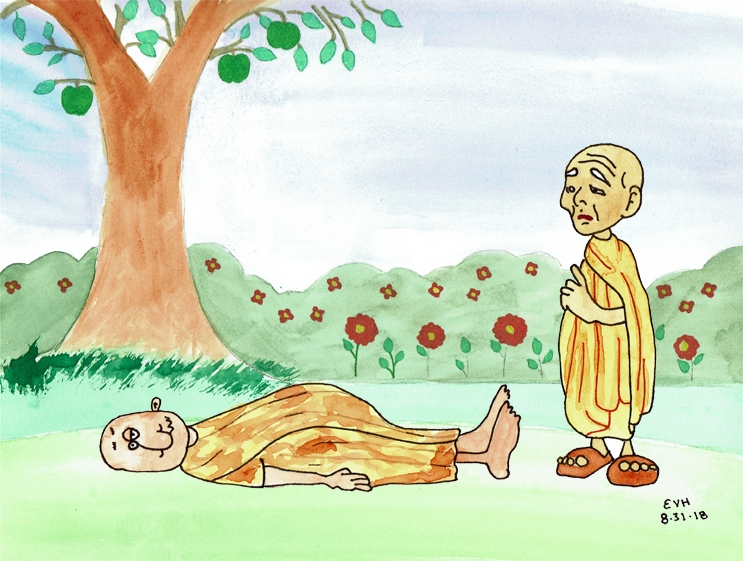

“To be sure we can,” the townsfolk said, and they invited the Master to take his meal with them next day. Then they went back to their town, and each one of them made arrangements to offer clear white liquor to the Elder. Accordingly, they subsequently invited the Elder in and plied him with the liquor, house by house. He drank so much that on his way out of town, the Elder fell down in the gateway and lay there hiccupping. On his way back from his meal in the town, the Master came on the Elder lying in this state and told the monks to carry Sāgata home. Then he went to the park.

The monks laid the Elder down with his head at the Buddha’s feet, but he turned around so that he came to lie with his feet pointing towards the Buddha. (In Asia, pointing your feet toward someone or a statue of the Buddha is very disrespectful.) Then the Master asked, “Monks, does Sāgata show respect to me like he used to?”

“No, sir.”

“Tell me, monks, who was it that overcame the Naga king of the Mango Ferry?”

“It was Sāgata, sir.”

“Do you think that in his present state Sāgata could overcome even a harmless water snake?”

“That he could not, sir.”

“Well now, monks, is it proper to drink anything that steals away a man’s senses?”

“It is improper, sir.”

Figure: The Drunken Sot Sāgata Disrespecting the Bodhisatta

Now, after speaking to the monks in criticism of the Elder, the Blessed One created the rule that drinking intoxicants was an offense requiring confession and absolution. (In the Vinaya there are eight categories of offenses. Ones that require confession are “pacittiya offenses,” and are the fifth most serious.) After that he got up and passed into his perfumed chamber.

Gathering together in the Dharma Hall, the monks discussed the offense of becoming intoxicated, saying, “Becoming intoxicated does such harm that it has blinded even one as wise and gifted as Sāgata to the Buddha’s excellence.” Entering the Dharma Hall at that point, the Master asked what they were discussing, and they told him. “Monks,” he said, “this is not the first time that a renunciate lost his senses through intoxication. The very same thing happened in bygone days.” And so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born into a northern brahmin family in Kāsi. When he grew up, he renounced the world for the life of a recluse. He won the Higher Knowledges (supernormal powers) and the Attainments (jhānas), and he lived in the bliss of Insight in the Himalayas with 500 pupils around him.

Once, during the rainy season, his pupils said to him, “Master, may we go to the world of men and bring back salt and vinegar?”

“For my own part, sirs, I will remain here. But you may go for your health’s sake. Come back when the rainy season is over.”

“Very good,” they said. And taking respectful leave of their Master, they went to Benares.

On the next day they went to a village just outside the city gates to gather alms. They had plenty to eat, and on the following day they went into the city itself. The kindly citizens gave alms to them, and the King was soon informed that 500 recluses from the Himalayas had taken up residence in the royal pleasure garden. He was told that they were recluses of great austerity, had overcome sensual desire, and that they were of great virtue.

Hearing this good report about them, the King went to the garden and graciously welcomed them, and he invited them to stay there for the rainy season. They promised that they would, and afterwards they were fed in the royal palace and lodged in the pleasure garden.

But one day a drinking festival was held in the city, and the King gave the 500 recluses a large supply of the best spirits, knowing that such things rarely come to those who renounce the world. The recluses drank the liquor and went back to the pleasure garden. There, in drunken hilarity, some danced, some sang, and others - who were tired of dancing and singing - trampled their rice baskets and other belongings. After that they lay down to sleep.

When they had slept off their drunkenness and awoke to see the results of their revelry, they wept and lamented, saying, “We have behaved badly. We have done this evil because we are away from our Master.” So they left the pleasure garden and returned to the Himalayas. Laying aside their bowls and other belongings, they saluted their Master and took their seats. “Well, my sons,” he said, “were you comfortable amid the world of men, and were you able to easily obtain alms? Did you live in harmony with one another?”

“Yes, Master, we were comfortable. But we drank strong spirits, and losing our senses and forgetting ourselves, we danced and sang.” And to illustrate what had happened, they composed and repeated this stanza:

We drank, we danced, we sang, we wept.

We were lucky that when we drank what steals away

The senses, we were not transformed into apes.

“This is what will certainly happen to those who are not living under a Master’s care,” the Bodhisatta said, rebuking those recluses. And he urged them on, saying, “From now on, never do such a thing again.” Living on with unbroken wisdom, he was later reborn in the Brahma Realm.

His lesson ended, the Master identified the birth and showed the connection by saying, “My disciples were the band of recluses of those days, and I was their teacher.”