Jataka 92

Mahāsāra Jātaka

The Great Essence

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story features two of the most wonderful people from the Buddha’s time, his personal attendant Ānanda and King Pasenadi, who is only identified in this story as the “King of Kosala.” It is noteworthy that King Pasenadi’s wives, which included the wise and endearing Queen Mallikā, wanted to learn the Dharma. It is equally noteworthy that in an extremely sexist society, that the King agreed.

In the story in the present, the layman, who has attained the very high goal of non-returning, does not agree to teach the King’s wives because he is not a monk. This shows the high regard that he has for the monastics, even if his attainment might be greater than theirs.

The stories themselves ramble and are a little confused, but I think you can see that their purpose is to extol the virtues of Ānanda.

“The wise monk.” This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana. It is about the venerable Ānanda.

The King of Kosala’s wives once thought to themselves, “The coming of a Buddha is very rare, and birth in a human form with all one’s faculties in perfection is very rare. Yet, although we have attained human form in a Buddha’s lifetime, we cannot go when we want to the monastery to hear the Dharma from his own lips, to pay our respects, and to make offerings to him. We live here like we are locked in a box. Let us ask the King to send for an appropriate monk to come here and teach us the Dharma. Let us learn what we can from him and be charitable and do good works so that we may profit by our having been born at this happy time.” So they went as a group to the King and told him what was on their minds, and the King gave his consent.

Now one day the King decided to enjoy himself in the royal pleasure garden. He gave orders that the grounds should be prepared for his arrival. As the gardener was working away, he saw the Master sitting at the foot of a tree. So he went to the King and said, “The pleasure garden is ready, sire, but the Blessed One is sitting there at the foot of a tree.”

“Very well,” the King said, “we will go and hear the Master.” Mounting his chariot of state, he went to the Master in the pleasure garden.

Now a lay-brother named Chattapāṇi was seated at the Master’s feet listening to his teaching. Chattapāṇi had attained the fruit of the Third Path, non-returning. Seeing this lay-brother, the King hesitated. But he reflected that this must be a virtuous man or he would not be sitting by the Master for instruction. So he approached and with a bow sat down on one side of the Master.

Out of reverence for the supreme Buddha, the lay-brother neither rose in the King’s honor nor saluted his majesty. This made the King very angry. Noticing the King’s displeasure, the Master proceeded to praise the merits of that lay-brother, saying, “Sire, this lay-brother is a master of all tradition. He knows the scriptures that have been handed down by heart, and he has set himself free from the bondage of passion.” (Non-returners have overcome sense desire.)

“Surely,” the King thought, “anyone who has earned the praise of the Master is no ordinary person.” And he said to him, “Let me know, lay-brother, if you need anything.”

“Thank you,” said the man. Then the King listened to the Master’s teaching, and at its close he arose and ceremoniously withdrew.

On another day, after breakfast, the King met that same lay-brother going, umbrella in hand, to Jetavana. The King summoned him to his presence and said, “I hear, lay-brother, that you are a man of great learning. My wives are very anxious to hear and learn the Dharma. I would be glad if you would teach them.”

“It is not appropriate, sire, that a layman should expound or teach the Dharma in the King’s harem. That is the prerogative of the Saṇgha.”

Recognizing the force of this remark, the King, after dismissing the layman, called his wives together. He announced his intention to ask the Master to send one of the monks to come as their instructor in the Dharma. Which of the 80 chief disciples would they have? After talking it over together, the ladies unanimously chose Ānanda the Elder, the Guardian of the Dhamma. (Ānanda was particularly sensitive to women’s issues, having convinced the Buddha to ordain women.)

So the King went to the Master and with a courteous greeting sat down by his side. He proceeded to state his wives’ wish - and his own hope - that Ānanda might be their teacher. The Master consented to sending Ānanda, and the King’s wives now began to be regularly taught by the Elder and to learn from him.

One day the jewel in the King’s turban went missing. When the King heard of the loss he sent for his ministers and ordered them to seize everyone who had access to the grounds and find the jewel. So the Ministers searched everybody, women and all, for the missing jewel, until they had worried everybody almost out of their minds. Yet they could find no trace of it.

That day Ānanda came to the palace, only to find the King’s wives as dejected as they had previously been delighted when he taught them. “What has made you like this today?” the Elder asked.

“Oh, sir,” they said, “the King has lost the jewel from his turban. By his orders the ministers are worrying everybody, women and all, out of their minds, in order to find it. We can’t say what might happen to anyone of us, and that is why we are so sad.”

“Don’t think any more about it,” the Elder said cheerfully, and he went to find the King. Taking the seat set for him, the Elder asked whether it was true that his majesty had lost his jewel.

“Quite true, sir,” the King said.

“And it cannot be found?”

“I have had all the residents of the palaces worried out of their minds, and yet I still can’t find it.”

“There is one way, sire, to find it, without worrying people out of their minds.”

“What way is that, sir?”

“By bunch-giving, sire.”

“Bunch-giving? What is that?”

“Call everyone together, sire, all the persons you suspect, and privately give each one of them a bunch of straw - a lump of clay will do also - saying, ‘Take this and put it in such and such a place tomorrow at daybreak.’ The man that took the jewel will put it in the straw or clay, and so return it. If it is brought back the very first day, well and good. If not, the same thing must be done on the second and third days. In this way, a large number of persons will escape worry, and you will get your jewel back.” With these words the Elder left.

Following this advice, the King caused the straw and clay to be dealt out for three successive days. But the jewel was still not recovered. On the third day the Elder came again. He asked whether the jewel had been brought back.

“No, sir,” the King said.

“Then, sire, you must have a large water pot put in a secluded corner of your courtyard, and you must have the pot filled with water and put a screen in front of it. Then give orders that all who visit the grounds, men and women alike, are to take off their outer garments, and one by one wash their hands behind the screen and then come back.” With this advice the Elder departed. And the King did as he was told.

The thief thought, “Ānanda has taken this matter seriously. And if he does not find the jewel, he’ll keep trying until he does. I better return the jewel.”

So he hid the jewel on his body, went behind the screen, and dropped it in the water before he left. When everyone had gone, the pot was emptied, and the jewel was found.

“It's all because of the Elder,” the King exclaimed in his joy, “that I have my jewel back, and that happened without worrying a lot of people out of their minds.”

All the people were grateful to Ānanda for the trouble from which he had saved them. The story about how Ānanda’s wisdom had found the jewel spread throughout the city until it reached the Saṇgha. The monks said, “The great knowledge, learning, and cleverness of the Elder Ānanda enabled recovery of the lost jewel and saved many people from being worried out of their minds.”

As they sat together in the Dharma Hall singing the praises of Ānanda, the Master entered and asked what was the topic of their conversation. Being told, he said, “Monks, this is not the first time that something stolen was found, and Ānanda is not the only one who brought this about. In bygone days, too, the wise and good discovered what had been stolen, and also saved many people from trouble, restoring lost property that had fallen into the hands of animals.” So saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta, having completed his education, became one of the King’s ministers. One day the King and a large following went into his pleasure garden. After going for a walk in the woods, he decided to go into the water. So he went down to the royal pond and sent for his harem. The women of the harem, removing the jewels from their heads and necks and so forth, put them aside with their upper garments in boxes under the charge of female slaves and then went down into the water.

Now, as the queen was taking off her jewels and ornaments and laying them with her upper robe in a box, a female monkey who was hidden in the branches of a nearby tree watched her. Longing to wear the queen’s pearl necklace, this monkey watched for the slave in charge to be off her guard. At first the girl kept looking all about her in order to keep the jewels safe. But as time went by, she began to doze off. As soon as the monkey saw this, she jumped down as quick as the wind. And as quick as the wind she was back up the tree again with the pearls around her neck. Then, for fear the other monkeys would see it, she hid the string of pearls in a hole in the tree and sat guard over her spoils as demurely as though nothing had happened.

By and by the slave awoke, and, terrified at finding the jewels gone, saw nothing else to do but to scream out, “A man has run off with the queen’s pearl necklace.” The guards ran up from every side, and hearing this story they told it to the King.

“Catch the thief!” his majesty said, and off went the guards searching high and low for the thief in the pleasure garden.

Hearing the uproar, a poor, superstitious peasant farmer ran away in alarm. “There he goes,” the guards cried, catching sight of the runaway. They followed him until they caught him, and with blows demanded what he meant by stealing such precious jewels.

He thought, “If I deny the charge, they will beat me to death. I'd better say I took it.” So he confessed to the theft and was hauled off to the King as a prisoner.

“Did you take those precious jewels?” the King asked.

“Yes, your majesty.”

“Where are they now?”

“Please your majesty, I’m a poor man. I’ve never owned anything in my life of any value, not even a bed or a chair, much less a jewel. It was the Treasurer who made me take that valuable necklace. I took it and gave it to him. He knows all about it.”

Then the King sent for the Treasurer. He asked whether the peasant had passed the necklace on to him.

“Yes, sire,” was the answer.

“Where is it then?”

“I gave it to your majesty’s priest.”

Then the priest was sent for. He was interrogated in the same way. And he said he had given it to the Chief Musician, who in his turn said he had given it to a courtesan as a present. But she, being brought before the King, denied ever having received it.

While the five were being questioned, the sun set. “It’s too late now,” the King said. “We will look into this tomorrow.” So he handed the five over to his ministers and went back into the city.

It was at about that time that the Bodhisatta started thinking. “These jewels,” he thought, “were lost inside the grounds, but the peasant was outside. There was a strong guard at the gates, and it was impossible for anyone inside to get away with the necklace. I do not see how anyone, whether inside or out, could have managed to secure it. The truth is this poor wretched fellow must have said he gave it to the Treasurer in order to save his own skin. And the Treasurer must have said he gave it to the priest in the hope that he would get off if he could get the priest mixed up in the affair. Further, the priest must have said he gave it to the Chief Musician, because he thought the latter would make the time pass merrily in prison. Then the Chief Musician implicated the courtesan simply to console himself with her company during imprisonment. Not one of the five has anything to do with the theft. On the other hand, the ground is swarmed with monkeys, and the necklace must have got into the hands of one of them.”

Once he arrived at this conclusion, the Bodhisatta went to the King and asked for the suspects to be handed over to him so he could look into the matter personally. “By all means, my wise friend,” the King said. “Look into it.”

The Bodhisatta sent for his servants and told them where to keep the five prisoners, saying, “Keep strict watch over them. Listen to everything they say and report it all to me.” And his servants did as he told them. As the prisoners sat together, the Treasurer said to the peasant, “Tell me, you wretch, where you and I ever met before this day. Tell me when you gave me that necklace.”

“Esteemed sir,” said the man, “I have never owned anything as valuable as even a stool or bedstead that wasn’t rickety. I thought that with your help I would get out of this trouble, and that's why I said what I did. Do not be angry with me, my lord.”

In turn, the priest said to the Treasurer, “Why did you pass on to me what this fellow never gave you?”

“I only said that because I thought that if you and I, both high officers of state, stand together, we can soon put things right.”

“Brahmin,” the Chief Musician then said to the priest, “when did you give the jewel to me?”

“I only said I did,” answered the priest, “because I thought you would help to make the time in prison pass more agreeably.”

Lastly the courtesan said, “Oh, you wretch of a musician, you know you never visited me, nor I you. So when could you have given me the necklace, as you say?”

“Why be angry, my dear?” the musician said. “We five have got to be together for a bit, so let us put a cheerful face on it and be happy together.”

This conversation was reported to the Bodhisatta by his agents. He was convinced the five were all innocent of the robbery, and that a female monkey had taken the necklace. “And I must find a way to make her drop it,” he said to himself.

So he had a number of bead necklaces made. Next he had a number of monkeys caught and turned loose again, with strings of beads on their necks, wrists, and ankles. Meantime, the guilty monkey kept sitting in the trees watching her treasure. The Bodhisatta ordered a number of men to carefully watch every monkey in the grounds until they saw one wearing the missing pearl necklace. Then they could frighten her into dropping it.

Tricked out in their new splendor, the other monkeys strutted about until they came to the real thief, before whom they flaunted their finery. Jealousy overcame her good judgment. She exclaimed, “They're only beads!” and she put on her own necklace of real pearls. The watchers saw this at once. They promptly made her drop the necklace which they picked up and brought to the Bodhisatta. He took it to the King, saying, “Here, sire, is the necklace. The five prisoners are innocent. It was a female monkey in the pleasure garden that took it.”

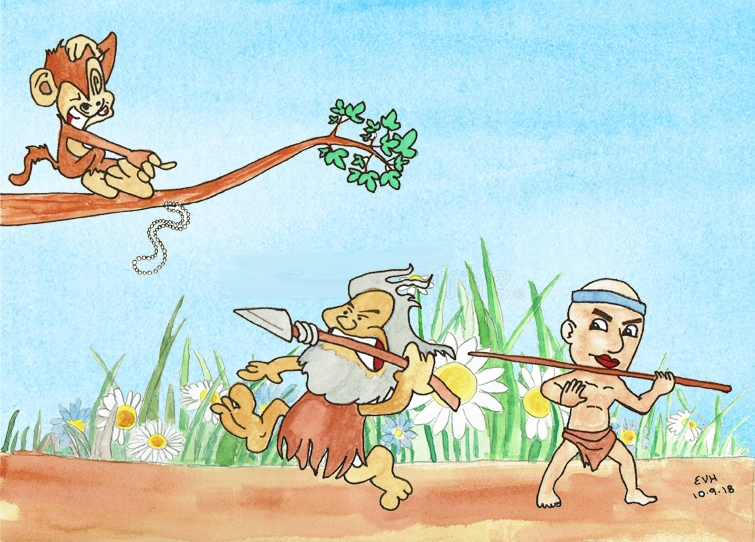

Figure: One Frightened Monkey!

“How did you figure that out?” asked the King. “And how did you manage to get it back again?”

Then the Bodhisatta told the whole story. The King thanked the Bodhisatta, saying, “You are the right man in the right place.” And he uttered this stanza in praise of the Bodhisatta:

Men crave the hero’s might for war,

For counsel sage sobriety,

Comrades for their revelry,

But judgment when in desperate plight.

In addition to these words of praise and gratitude, the King showered the Bodhisatta with treasures like a storm cloud pouring rain from the heavens. After following the Bodhisatta’s advice through a long life spent in charity and good works, the King passed away to fare according to his karma.

His lesson ended, the Master, after praising the Elder’s merits, identified the birth by saying, “Ānanda was the King of those days, and I was his wise counsellor.”