Jataka 94

Lomahaṃsa Jātaka

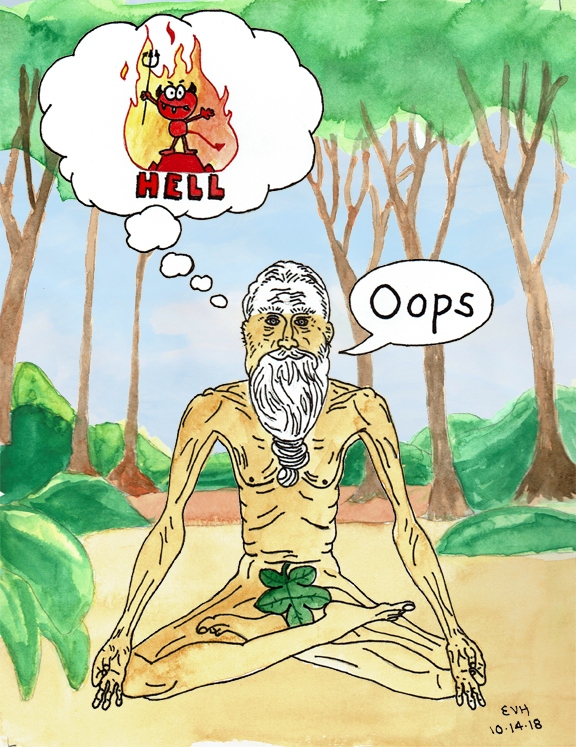

The Naked Ascetic

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story is probably hard to relate to for most Westerners. But in India – and this is true even now – there is a tradition of asceticism. (There are some parallels in Western Christianity.) The theory is that you can liberate yourself from the rounds of rebirth through self-mortification. While the Budddaharma does teach simplicity and restraint, the Buddha also spoke out against such extreme practices. It is the famous “middle way,” the path that lies between self-indulgence and self-torture.

“Now scorched.” The Master told this story while at Pāṭikārāma near Vesāli. It is about Sunakkhatta.

Sunakkhatta was a follower of the Master. He was travelling around the country as a monk with bowl and robes, but he was converted to the tenets of Kora the Kshatriya. (Kora was an ascetic who “crept on his hands and feet; touched nothing with his hands, but took all things up with his mouth, even drank without using his hand; and lay in ashes.” – [Hardy’s Manual of Buddhism, p. 330]. According to the story, Kora thought he was an arahant. The Buddha warned him that this was not so, that he was going to die in six days, and if he did not correct his error, he would be reborn as an “asura” with a body 12 miles high but without flesh and blood and with eyes on top of his head like a crab!) So Sunakkhatta returned his bowl and robes to the Blessed Buddha and reverted to lay life as a follower of Kora the Kshatriya.

It was at about that time when Kora was reborn as the child of the Kālakañjaka Asura. Sunakkhatta went around Vesāli defaming the Master by affirming that there was nothing superhuman about the sage Gotama. He said that the Master was not distinguished from other men by teaching a liberating faith. He said that he had simply worked out a system that was the outcome of his own thought and study, and that his doctrine did not lead to the destruction of sorrow in those who followed it. (This is a quote from the Majjhima Nikāya 12.2. The criticism here is that the Buddha taught a doctrine that he had worked out by thinking rather than one he had experienced directly.)

Now the reverend Sāriputta was on his alms round when he heard Sunakkhatta’s affronts. When he returned from his round, he reported this to the Blessed One. The Master said, “Sunakkhatta is a reckless person, Sāriputta, and he speaks idle words. His recklessness has led him to talk like this and to deny the liberating wisdom of my doctrine. He has no knowledge of my attainment. In me, Sāriputta, the Six Knowledges live. (These are supernormal powers. Part of the implication of Sunakkhatta’s criticism is that the Buddha does not have any supernormal powers.) Therefore I am more than human. I have within me the Ten Powers (the powers of knowledge that are attained by all Buddhas), and the Four Grounds of Confidence (also features of a Buddha). I know the limits of the four types of earthly existence and the five states of possible rebirth after earthly death (hell, hungry ghost, animal, human, and heaven). This, too, is a superhuman quality in me. Whoever denies it must take back his words, change his belief, and renounce his heresy, or he will be cast into hell.”

Having declared his superhuman nature and the power that existed within him, the Master went on to say, “Sāriputta, I hear that Sunakkhatta took delight in the misguided self-mortifications of the asceticism of Kora the Kshatriya. Therefore, he could take no pleasure in me. Ninety-one eons ago I lived the higher life in all its four forms (“learner”, householder, religious person, and recluse). I examined that false asceticism to discover whether there is any truth in it. I was an ascetic, the chief of ascetics. I was worn and emaciated beyond all others. I loathed comfort. My loathing surpassed that of all others. I lived apart, and my passion for solitude was unapproachable.” Then, at the Elder’s request, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time, ninety-one eons ago, the Bodhisatta decided to examine false asceticism. So he became a recluse, a Naked Ascetic (an Ājīvika). He was naked and covered with dust, solitary and lonely, fleeing like a deer from the faces of men. He ate small fish, cow dung, and other refuse. In order to keep his vigil undisturbed, he lived in a dreaded dense grove of trees in the jungle. He came out at night from the sheltering thicket into the open air and winter snow. He returned at sunrise to his thicket again. He was wet with the driving snows at night. In the day time he was drenched by the drizzle from the branches of the thicket. Day and night he endured the extremity of cold. In summer, he lived in the open air during the day, and at night he lived in the forest. He was scorched by the blazing sun during the day, but he was not cooled by breezes by night. The sweat streamed from him. And a poem came into his mind. It was new and had never been uttered before:

Now scorched, now frozen, alone in the lonesome woods,

Beside no fire, but all afire within,

Naked, the hermit wrestles for the truth.

But after a life spent in the rigors of this asceticism, the vision of hell rose before the Bodhisatta as he lay dying. He realized the worthlessness of all his austerities. In that supreme moment he broke away from his delusion. He laid hold of the real truth and was reborn in the Heaven of Devas.

Figure: Just In Time

His lesson ended, the Master identified the birth by saying, “I was the naked ascetic of those days.”