Jataka 97

Namāsiddhi Jātaka

The Lucky Name

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is another story that addresses the issue of superstition.

I heard a great story about this topic from Ajahn Brahm. Superstition is still very much a part of some Asian cultures. When the great Thai forest master Ajahn Chah was at his monastery one day, a man came up to him and asked Ajahn Chah to tell him his fortune. Fortune telling is still all the rage in Thailand.

Ajahn Chah at first refused, because – of course – he could not tell anyone their future. But the man complained. He said that he had always been a big supporter of the monastery. He was always there for the special events. Now he just wanted one simple thing from Ajahn Chah, and he was refusing.

So finally Ajahn Chah agreed. He made a big show of it. He took the man’s hand and used his finger to follow every line in it. He grunted and grumbled, and then he finally started to speak. “Your future,” he began – just as the man looked with great anticipation – “your future,” he said, “is very uncertain.”

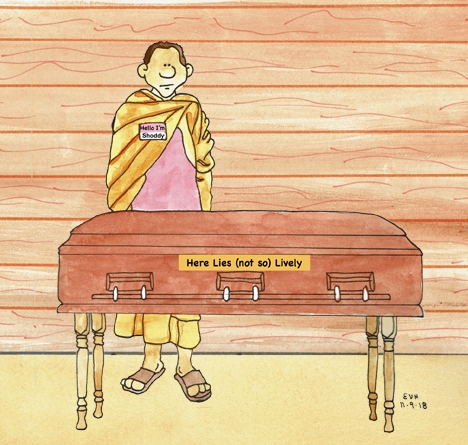

“Seeing Lively dead.” This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana. It is about a monk who thought that luck was determined by your name. For we hear that a young man named “Shoddy,” who was from a good family, had given his heart to the Dharma and joined the Saṇgha. The monks used to call to him, “Here, Brother Shoddy!” and “Stay, Brother Shoddy,” until he resolved that, because the name “Shoddy” indicated wickedness and bad luck, he would change his name to one that would bring him good fortune.

Accordingly he asked his teachers and preceptors to give him a new name. But they said that a name only served to indicate a person but did not define qualities. They tried to convince him to be contented with the name he had. Time after time he renewed his request, until the whole Saṇgha knew how much importance he attached to a mere name.

One day they sat discussing the matter in the Dharma Hall, and the Master entered and asked what they were discussing. Being told, he said “This is not the first time this monk has believed that luck was determined by a name. He was just as dissatisfied with the name he had in a former age.” So saying he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time the Bodhisatta was a teacher of worldwide fame at Takkasilā University, and 500 young brahmins learned the Vedas from him. One of these young men was named “Shoddy.” And from constantly hearing his fellow students say, “Go, Shoddy” and “Come, Shoddy,” he longed to get rid of his name and to take one that had a less ominous ring to it. So he went to his master and asked to be given a new name, one that would give him a respectable character. His master said, “Go, my son, and travel through the land until you have found a name you like. Then come back and I will change your name for you.”

The young man did as he was told. Taking provisions for the journey, he wandered from village to village until he came to a certain town. Here a man named “Lively” had died. The young brahmin saw him being taken to the cemetery, and he asked what his name was.

“Lively,” was the reply.

“What, can Lively be dead?”

“Yes, Lively is dead. No matter what, someone named ‘Lively’ will die just the same. A name only serves to mark who’s who. You seem like a fool.”

Figure: Not So Lively

Hearing this he went on into the city, feeling neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with his own name.

Now a servant girl had been thrown down at the door of a house while her master and mistress beat her with a rope because she had not brought home her wages. The girl’s name was Rich. Seeing the girl being beaten as he walked along the street, he asked why she was being beaten. He was told that it was because she had no wages to show for her work.

“And what is the girl’s name?”

“Rich,” they said.

“And cannot Rich make good on a paltry day’s pay?”

“Whether she is called Rich or Poor, the money is not there. A name only serves to mark who’s who. You seem like a fool.”

Becoming more reconciled to his name, the young brahmin left the city. On the road he found a man who had lost his way. Having learned that he was lost, the young man asked what his name was. “Guide,” was the reply.

“And have you lost your way, Guide?”

“With a name like Guide or even Misguide, you can lose your way just the same. A name only serves to mark who’s who. You seem a fool.”

Quite reconciled now to his name, the young brahmin went back to his master.

“Well, what name have you chosen?” the Bodhisatta asked.

“Master,” he said, “I found that death comes to ‘Lively,’ that ‘Rich’ and ‘Poor’ may both be poor, and that ‘Guide’ and ‘Misguide’ alike can lose their way. I know now that a name serves only to tell who is who, and does not determine its owner’s destiny. So I am satisfied with my own name, and I do not want to change it.”

Then the Bodhisatta uttered this stanza, combining what the young brahmin had done with the sights he had seen:

Seeing Lively dead, Guide lost, Rich poor,

Shoddy became content and traveled no more.

His story told, the Master said “So you see, monks, that in former days as now this monk imagined there was a great deal in a name.” And he identified the birth by saying, “This monk who is discontented with his name was the discontented young brahmin of those days. The Buddha’s disciples were the pupils, and I myself was their master.”