Jataka 164

Gijja Jātaka

The Vulture

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a story about respect for one’s elders. Sadly, this is not a part of our Western culture. But I have seen it up close living in the southwestern U.S. where the two predominant cultures here – Hispanic and Native American – have this same respect for elders that is discussed in the Buddhist scriptures.

Just last week I was traveling through Farmington, New Mexico, which is just east of Navajo Nation. I pulled into a gas station where I saw an elderly Indian man coming out. He could barely walk. There was a young Indian man just hanging out leaning against the building. He quite deliberately went over to the man and helped him to his car. I thought they might have been related. But the young man just came back to the building while the old man was driven off. The young man was just doing what any self-respecting Navajo would do, and that was to help a respected older person.

The Buddha said this about one’s parents:

“I tell you, monks, there are two people who are not easy to repay. Which two? Your mother and father. Even if you were to carry your mother on one shoulder and your father on the other shoulder for 100 years, and were to look after them by anointing, massaging, bathing, and rubbing their limbs, and they were to defecate and urinate right there [on your shoulders], you would not in that way pay or repay your parents. If you were to establish your mother and father in absolute sovereignty over this great earth, abounding in the seven treasures, you would not in that way pay or repay your parents. Why is that? Mother and father do much for their children. They care for them, they nourish them, they introduce them to this world. But anyone who rouses his unbelieving mother and father, settles and establishes them in conviction; rouses his unvirtuous mother and father, settles and establishes them in virtue; rouses his stingy mother and father, settles and establishes them in generosity; rouses his foolish mother and father, settles and establishes them in discernment: To this extent one pays and repays one’s mother and father.” – [AN 2.33]

“A vulture sees a corpse.” The Master told this story about a monk who had his parents to support. The circumstances will be related under the Sāma Jātaka (Jātaka 540). The Master asked him whether he, a monk, was really supporting people who were living in the world. The monk admitted that this was true.

“How are these people related to you?” the Master went on.

“They are my parents, sir.”

“Excellent, excellent,” the Master said, and he told the other monks not be angry with him. “Wise men of old,” he said, “have done service even to those who were not related to them, but this man’s task has been to support his own parents.” So saying, he told them this story of the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmavatta was the King of Benares, the Bodhisatta was reborn as a young vulture on Vulture Peak (this was the Buddha’s favorite place to meditate), and he had to care for his mother and father.

Once there was a great wind and rain. The vultures could not hold their own against it. Half frozen, they flew to Benares, and there they sat, shivering with cold near the wall and the ditch.

A merchant of Benares was just then leaving the city on his way to bathe when he saw these miserable vultures. He got them together in a dry place, made a fire, sent for and brought them some meat from the cattle’s burning-place, and put someone in charge to look after them.

When the storm ended, our vultures were all right and flew off at once back to the mountains. There they met and discussed what had happened. “A Benares merchant has been kind to us, and ‘one good turn deserves another,’ as the saying goes. So after this when any of us finds some clothing or jewelry it must be dropped in that merchant’s courtyard.”

So from then on if they ever noticed people drying their clothes in the sun, they watching for an unwary moment and snatched them quickly just as hawks pounce on a bit of meat. Then they dropped them in the merchant’s yard. But he, whenever he saw that they were bringing him anything, had whatever they brought put aside.

The victims of the vultures’ crimes told the King how they were plundering the city. “Just catch me one vulture,” the King said, “and I will make them bring it all back.” So snares and traps were set everywhere, and our dutiful vulture was caught.

They seized him with the intention of taking him to the King. The merchant, however, was on his way to wait upon his majesty. He saw these people walking with the vulture. He went with them for fear that they might hurt the vulture.

They gave the vulture to the King, who proceeded to question him.

“You rob our city and carry off clothes and all sorts of things,” he began.

“Yes, sire.”

“To whom have these things been given”

“A merchant of Benares.”

“Why?” asked the King

“Because he saved our lives, and they say that one good turn deserves another. That is why we gave them to him.”

“They say that vultures can see a corpse 500 kilometers away,” the King said. “Why can’t you see a trap that is set for you?” And with these words he repeated the first stanza:

“A vulture sees a corpse that lies 500 kilometers away.”

When you land on a trap don’t you see it, pray?”

The vulture listened, then replied by repeating the second stanza:

“My parents’ hour of death draws near, and soon their lives will cease.

I sprung the trap to keep them safe, so they may die in peace.”

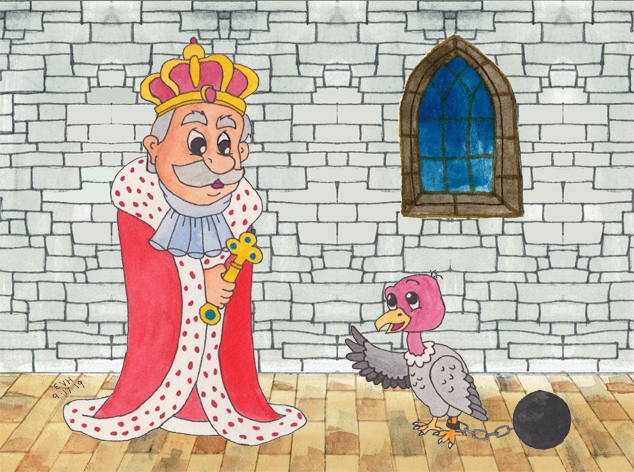

Figure: The Vulture Explains

After the vulture responded the King turned to our merchant. “Have all these things really been brought to you, then, by the vultures?”

“Yes, my lord,” he said.

“Where are they?”

“My lord, I have stored them all away. Everyone will receive his own property back. But please let this vulture go!”

He had his way. The vulture was set free, and the merchant returned all the property to its owners.

This lesson ended, the Master taught the Four Noble Truths. At the conclusion of the discourse the dutiful monk attained fruition of the First Path, stream-entry. Then the Master identified the birth: “Ānanda was the King of those days. Sāriputta was the merchant, and I was the vulture who supported his parents.”