Jataka 220

Dhammaddhaja Jātaka

The Story of Dhammaddhaja

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This Jātaka spins a nice little tale in which the Bodhisatta is tested over and over again to do “impossible” tasks. The mastermind behind these tests is our old friend Devadatta. But in this case the Bodhisatta is repeatedly bailed out by Sakka, the Lord of the devas.

This story gives us some insight into how Buddhism regards Sakka. Sakka is known in Hinduism as “Indra.” In Buddhism, Sakka takes on the role of a benevolent protector of the Dharma. And in this story, he protects the Bodhisatta himself.

The punch line to this story is a lovely one. The Bodhisatta is given a task that Sakka cannot complete and that is to find a truly virtuous man. The Bodhisatta is able to do this with Sakka’s help, and this ends the stream of tests that the Bodhisatta is ordered to complete.

“You look as though…” The Master told this story while he was staying at the Bamboo Grove (Veluvana). It is about the attempts to kill him. On this occasion, as before, the Master said, “This is not the first time Devadatta has tried to murder me, yet has not even frightened me. He did the same before.” And he told this story from the past.

Once upon a time there reigned a King named “Yasapāṇi the Glorious” in Benares. His chief captain was named “Kāḷaka,” or “Blackie.” At that time the Bodhisatta was his chaplain. He had the name “Dhammaddhaja, the Banner of the Faith.” There was also a man named “Chattapāṇi.” He was the maker of ornaments for the King. The King was a good king. But his chief captain took bribes when judging cases. He was a backstabber. He took bribes and defrauded the rightful owners.

One day, someone who had lost his lawsuit was leaving the court. He was weeping and stretching out his arms when he saw the Bodhisatta who was on his way to pay his service to the King. Falling at his feet the man cried out, telling the Bodhisatta how he had lost his case. “Although people like you, my lord, instruct the King in the ways of this world and the next, the Commander-in-Chief takes bribes and defrauds rightful owners!”

The Bodhisatta felt compassion for him. “Come, my good fellow,” he said, “I will judge your case for you,” and he proceeded to the courthouse. A great many people gathered together. The Bodhisatta reversed the sentence and gave a judgment in his favor. The spectators applauded. The sound was deafening. The King heard it and asked, “What is all that noise that I hear?"

“My lord King,” they answered, “it is a case wrongly judged that has been made right by the wise Dhammaddhaja. That is why there is this roar of applause.”

The King was pleased and sent for the Bodhisatta. “They tell me,” he began, “that you have judged a case?”

“Yes, great King. I have judged a case that Kāḷaka did not judge properly.”

“You will be a judge from this day on,” said the King. “It will be a joy for my ears and mean prosperity for the world!”

Dhammaddhaja was at first unwilling to do this, but the King begged him. “In mercy to all creatures, please sit in judgment!” And so the King was able to get him to agree.

From that time Kāḷaka received no gifts. Having lost his gains he slandered the Bodhisatta before the King, saying, “Oh mighty King, the wise Dhammaddhaja covets your kingdom!” But the King did not believe him and told him not to say such things.

“If you do not believe me,” said Kāḷaka, “look out of the window when he arrives at the palace. Then you will see that he has got the whole city in his hands.”

The King saw the great crowd of people who were gathered around him in his judgment hall. “There are his supporters,” the King thought. He gave in to Kāḷaka. “What are we to do, Captain?” he asked.

“My lord, he must be put to death.”

“How can we put him to death without having found him guilty of some crime?”

“There is a way,” Kāḷaka said.

“How?”

“Tell him to do something that is impossible, and when he cannot do it, put him to death for that.”

“But what is impossible to him?”

“My lord King,” he replied, “it takes two to four years for a garden with good soil to bear fruit. Send for him and say, ‘We want a pleasure garden planted tomorrow. Make us a garden!’ He will not be able to this, and we will put him to death for that fault.”

The King addressed the Bodhisatta. “Wise sir, we have enjoyed our old garden long enough. Now we want a new one. Make us a garden! If you cannot make it, you must die.”

The Bodhisatta reasoned, “It must be that Kāḷaka has turned the King against me because he is no longer getting presents.”

“If I can,” he said, “Oh mighty King, I will see to it.”

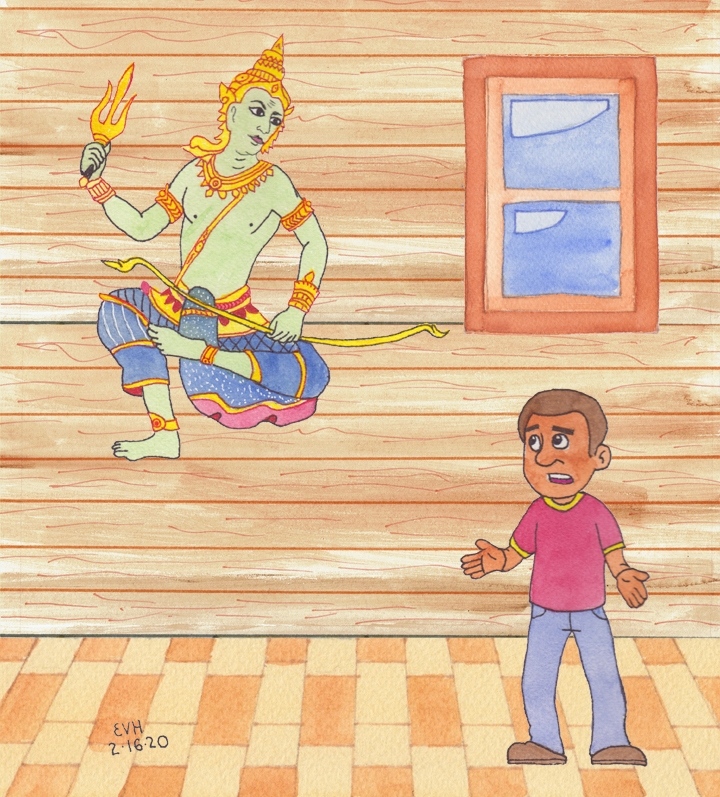

And he went home. After a good meal he lay on his bed thinking. Sakka’s palace grew hot. (“Sakka” is the King of the Devas. In Indian mythology Sakka’s palace grew hot when someone was in dire straits.) Sakka perceived the Bodhisatta’s difficulty. He rushed to him, entered his chamber, and – poised in mid-air - asked him, “Wise sir, what are you thinking about?”

“Who are you?” the Bodhisatta asked.

“I am Sakka.”

“The King has told me to make a garden. That is what I am thinking about.”

Figure: Explaining the Dilemma to Sakka

“Wise sir, do not worry. I will make you a garden like the groves of Nandana (Sakka’s own garden) and Cittalatā (the garden in the Heaven of the Thirty-three)! Where should I put it?”

He told him where to put it. Sakka made the garden and then returned to the city of the gods.

On the next day, the Bodhisatta looked over the garden, and then he went to the King. “Oh King, the garden is ready. Go and enjoy it!”

The King went to the place, and saw a garden surrounded by a fence of eighteen cubits. It was the color of vermilion. It had gates and ponds, beautifully covered with all types of trees laden heavy with flowers and fruit! “The sage has done what I have asked,” he said to Kāḷaka. “Now what are we going to do?”

“Oh mighty King!” he replied, “if he can make a garden in one night, can he not also seize your kingdom?”

“Well, what are we to do?”

“We will make him perform another impossible act.”

“What is that?” asked the King.

“We will have him build a lake full of the seven precious jewels!” (gold, silver, pearl, coral, catseye, ruby, and diamond)

The King agreed and thus addressed the Bodhisatta:

“Teacher, you have made a garden. Now make a lake to match it, filled with the seven precious jewels. If you cannot make it, you shall not live!”

“Very well, great King,” the Bodhisatta answered, "I will make it if I can.”

Then Sakka made a lake of great splendor. It had a hundred landings, a thousand inlets. It was covered with lotus plants of five different colors, just like the lake in Nandana.

On the next clay, the Bodhisatta surveyed this. He told the King, “See, the lake has been made!” When the King saw it he asked Kāḷaka what was to be done.

“Tell him, my lord, to make a house to suit it,” he said.

“Make a house, teacher,” the King said to the Bodhisatta. “Make it of ivory to suit the park and the lake. If you do not make it, you must die!”

Then Sakka built the house. The Bodhisatta saw it on the next day, and then he reported to the King. When the King saw it, he asked Kāḷaka - again - what was to be done. Kāḷaka told him to order the Bodhisatta to make a jewel to suit the house. The King said to him, “Wise sir, make a jewel to suit this ivory house. I will look at the house by the light of this jewel. If you cannot make it, you must die!”

Then Sakka made him a jewel as well. On the next day the Bodhisatta saw it, and then he reported to the King. When the King saw it, he again asked Kāḷaka what was to be done.

“Mighty King!” he answered, “I think there is some spirit who does each task that the brahmin Dhammaddhaja wishes. Now tell him to make something which even a god cannot make. Not even a god can make a man with all four virtues. Therefore, tell him to make a park ranger with these four.”

So the King said, “Teacher, you have made a park, a lake, and a palace, and a jewel to give light. Now make me a man with four virtues to watch the park. If you cannot, you must die.”

“So be it,” he answered, “if it is possible, I will do it.”

He went home, had a good meal, and lay down. When he woke up in the morning, he sat on his bed and thought, “What the great King Sakka can make by his power, he has made. But he cannot make a park ranger with four virtues. This being the case, it is better for me to die forlorn in the woods than to die at the hand of other men.”

So saying nothing to anyone, he left his home and went out of the city by the main gate. He went into the woods. There he sat him down underneath a tree and reflected upon the Dharma of the good. Sakka perceived it, and disguised as a forester he approached the Bodhisatta. He said, “Brahmin, you are young and tender. Why do you sit here in this wood in so much pain?” As he asked it, he repeated the first stanza:

“You look as though your life must happy be,

Yet to the wild woods you would homeless go,

Like some poor wretch whose life was misery,

And pine beneath this tree in lonely woe.”

To this the Bodhisatta answered in the second stanza:

“I look as though my life must happy be,

Yet to the wild woods I would homeless go,

Like some poor wretch whose life was misery,

And pine beneath this tree in lonely woe,

Pondering the truth that all the saints do know.”

Then Sakka said, “If so, then why, brahmin, are you sitting here?”

“The King,” he replied, “requires a park ranger with four good qualities. There is no one like that, so I thought, ‘Why perish by the hand of man? I will be off to the woods and die a lonely death. So here I came, and here I sit.”

Then Sakka replied, “Brahmin, I am Sakka, King of the gods. I made your park and those other things. A park ranger who has the four virtues cannot be found here. But in your country there is a man named “Chattapāṇi.” He makes ornaments for the head, and he is such a man. Go find him and make this man the park keeper.” With these words Sakka departed to his heavenly city after consoling Dhammaddhaja and telling him to fear no more.

The Bodhisatta went home, and having broken his fast, he went to the palace gates. There he saw Chattapāṇi. He took him by the hand and asked him, “Is it true, as I hear, Chattapāṇi, that you are endowed with the four virtues?”

“Who told you so?” Chattapāṇi asked.

“Sakka, King of the gods.”

“Why did he tell you?” He recounted it all.

Chattapāṇi said, “Yes, I am endowed with the four virtues.”

The Bodhisatta took him by the hand and led him into the King’s presence. “Here, mighty monarch, is Chattapāṇi. He is endowed with four virtues. If there is need of a keeper for the park, make him keeper.”

“Is it true, as I hear,” the King asked him, “that you have four virtues?”

“Yes, mighty King.”

“What are they?” he asked.

"I do not envy, I do not drink alcohol, I have no lust, and I never get angry,” he said.

“Why, Chattapāṇi,” cried the King, “did you say you have no envy?”

“Yes, oh King, I have no envy.”

“What are the things you do not envy?”

“Listen, my lord!” he said, and then he told him how he felt no envy in the following lines:

“A chaplain once in bonds I threw,

Which thing a woman made me do.

He built me up in holy lore,

Since when I never envied more.”

(This is a reference to Jātaka 120 in which Chattapāṇi became King because of his virtue.)

Then the King said, “Dear Chattapāṇi, why do you abstain from liquor?” And he answered in the following verse:

“Once I was drunken, and I ate

My own son’s flesh upon my plate,

Then, touched with sorrow and with pain,

Swore never to touch a drink again.”

Then the King said, “But what, dear sir, makes you indifferent, without love?” The man explained it in these words:

“King Kitavāsa was my name,

A mighty King was I,

My boy the Buddha’s basin broke

And so he had to die.”

Then the King said, “What was it, good friend, that made you to be without anger?” And he made the matter clear in these lines:

“As ‘Araka’ for seven years

I practiced charity,

And then for seven ages dwelt

In Brahma’s realm on high.”

When Chattapāṇi had explained his four virtues, the King signaled to his attendants. And in an instant the entire court - priests and laymen and everyone - rose up and cried out to Kāḷaka, “You bribe-swallowing thief and scoundrel! You couldn't get your bribes, and so you conspired to murder the wise man by slandering him!” They seized him by his hands and feet. They tied him up and carried him out of the palace, and picking up whatever they could get their hands on, stones and sticks and the like, they smashed his head until he died. Then they dragged him by the feet and threw his body on a pile of manure.

From then on the King ruled in righteousness until he passed away to fare according to his karma.

This discourse ended, the Master identified the birth: “Devadatta was the Commander Kāḷaka, Sāriputta was the artisan Chattapāṇi, and I was Dhammaddhaja.”