Jataka 222

Cūla Nandiya Jātaka

Little Nandiya

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is another story about Devadatta, but it is also a story about karma. Karma is an often-misunderstood concept in Buddhism. It is not deterministic, as this story may seem to imply. It is probabilistic. We all have good and bad karma, and either one can ripen at any time. This is why bad things can happen to good people, and good things can happy to bad people. The most telling line is in the final verse:

“And so our deeds are all like seeds.”

Unskillful actions plant negative karmic seeds, and vice versa.

There is also another teaching of the Buddha in this story, and that is the use of a healthy kind of shame:

“Be careful you should nothing do of which you might repent.”

A healthy sense of shame can prevent us from doing something we might regret. This is one of the skillful uses of mindfulness as we go about our daily tasks. We know that there are consequences to our actions, so we use care in what we think, say, and do.

This story also references a story from the Pāli Canon (it occurs in several places), and that is that Devadatta was “swallowed up by the earth.” It is possible that this means an earthquake, or perhaps it is a legend that was added later.

“I call to mind.” The Master told this story while staying at the Bamboo Grove (Veluvana). It is about Devadatta.

One day the monks were talking in the Dharma Hall: “Friends, that man Devadatta is harsh, cruel, and tyrannical, full of wicked attacks against the Supreme Buddha. He flung a stone (He tried to kill the Buddha by rolling a rock down a hill), he even used the aid of Nāḷāgiri (He got an elephant named “Nāḷāgiri” drunk then got him to attack the Buddha). There is no pity or compassion for the Tathāgata (the Buddha).”

The Master came in and asked what they were discussing as they sat there. They told him. Then he said, “This is not the first time, monks, that Devadatta has been harsh, cruel, and merciless. He was this way before.” And he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was the King of Benares, the Bodhisatta was reborn as a monkey named “Nandiya,” or “Jolly.” He lived in the Himalaya Mountains. His youngest brother bore the name “Jollikin.” The two of them headed a band of 80,000 monkeys, and they had a blind mother in their home for whom to care.

Once they left their mother in her refuge in the bushes, then they went into the trees to find sweet wild fruits of all kinds. They sent these back home to her. But the messengers did not deliver them, and - tormented with hunger - she became nothing but skin and bone.

When they returned the Bodhisatta said to her, “Mother, we sent you plenty of sweet fruits to eat. Why are you so thin?”

“My son, I never get them!”

The Bodhisatta pondered this. “While I look after my herd, my mother starves. I will leave the herd and only look after my mother.” So he said to his brother, “Brother, you tend to the herd, and I will care for our mother.”

“No, brother,” he replied, “I do not care about ruling a herd. I, too, will care for only our mother!” So the two of them were of one mind. And leaving the herd, they brought their mother down out of the Himalaya Mountains. They took up their home in a banyan tree in the border-land where they took care of her.

Now a certain brahmin who lived at Takkasilā University had received his education from a famous teacher. Afterward he decided to take leave of him and told him that he would depart. This teacher had the power of seeing into a man’s character from the signs on his body. Using his insight he perceived that his pupil was harsh, cruel, and violent. “My son,” he said, “you are harsh and cruel and violent. Such people do not prosper in all seasons. They come to dire woe and dire destruction. Do not be harsh, or you will come to regret your actions.” With this advice, he let him go.

The youth took leave of his teacher and went to Benares. There he married and settled down. But being unable to earn a livelihood by any of his other skills, he decided to do so using his bow. So he set about to work as a hunter. He left Benares to earn his living. Living in a border village, he roamed the woods armed with his bow and quiver, and he lived by selling the flesh of all manner of beasts which he killed.

One day, as he was returning home after having caught nothing in the forest, he saw a banyan tree standing on the edge of an open glade. “Perhaps,” he thought, “there will be something here.” So he headed to the banyan tree. Now the two brothers had just fed their mother with a meal of fruit. They were sitting behind her in the tree when they saw the man coming. “Even if he sees our mother,” they said, “what can he do?” and they hid in the branches.

Then this cruel man, as he came up to the tree and saw the mother monkey weak with age and also blind, thought to himself, “Why should I return empty-handed? I will shoot this monkey first!” He lifted up his bow to shoot her. The Bodhisatta saw this and said to his brother, “Jollikin, my dear, this man wants to shoot our mother! I will save her life. When I am dead, you take care of her.”

So saying, he came down out of the tree and called out, “Oh man, don’t shoot my mother! She is blind and weak from age. I will save her life. Don’t kill her but kill me instead!” The man agreed. Nandiya sat down in a place that was within bowshot. The hunter pitilessly shot the Bodhisatta. And when he dropped, the man prepared his bow to shoot the mother monkey. Jollikin saw this and thought to himself, “That hunter wants to shoot my mother. Even if she only lives a day, she will have received the gift of life. I will give my life for hers.” Accordingly, he came down from the tree and said, “Oh man, don’t shoot my mother! I give my life for hers. Shoot me. Take both of us brothers and spare our mother’s life!”

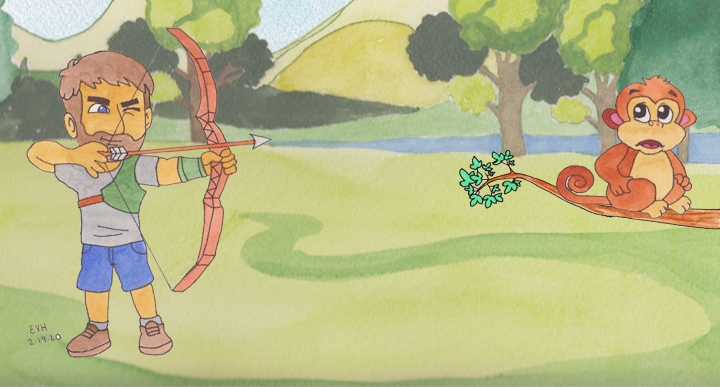

Figure: The Pitiless Hunter

The hunter agreed. Jollikin sat down within bowshot. The hunter shot him, too, and he killed him. “This will do for my children at home,” he thought, and he shot the mother, too. He hung all three of them on his carrying pole and set out for home.

At that very moment a thunderbolt struck the house of this wicked man. His wife and two children were burned to death. Nothing was left of the house but the roof and the bamboo uprights.

When the hunter entered the village a man met him and told him what had happened. The hunter was overcome with grief for his wife and children. He threw down his pole with the game on it as well as his bow right on the spot. He threw off his clothes and went home naked, wailing with his hands outstretched. When he got to the house the bamboo uprights broke. They fell on his head and crushed it. The earth yawned; flame leaped up from hell. As he was being swallowed up in the earth, he thought about his master’s warning: “Then this was the teaching that the Brahmin Pārāsariya gave me!” And lamenting he uttered these stanzas:

“I call to mind my teacher’s words: so this was what he meant!

Be careful you should nothing do of which you might repent.

“Whatever a man does, the same he in himself will find,

The good man, good, and evil he that evil has designed.

And so our deeds are all like seeds, and bring forth fruit in kind.”

Lamenting in this way, he went down into the earth and was reborn in the depths of hell.

Lamenting in this way, he went down into the earth and was reborn in the depths of hell.

In this way the Buddha showed how in other days, as then, Devadatta had been harsh, cruel, and merciless. When the Master had ended this discourse, he identified the birth in these words: “In those days Devadatta was the hunter, Sāriputta was the famous teacher, Ānanda was Jollikin, the noble Lady Gotamī (the Buddha’s birth mother) was the mother, and I was the monkey Jolly.”