Jataka 259

Tirīṭavaceha Jātaka

The Story of Master Tirīṭavaceha

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a simple but lovely story about an act of kindness and the gratitude of the recipient of that kindness. One of the things I love about this story is that the generous act of the recluse was done simply out of compassion without expecting any reward. That is the proper way to be kind and generous.

“When all alone.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about the gift of 1,000 garments, how the reverend Ānanda received 500 garments from the women of the household of the King of Kosala (King Pasenadi) and 500 from the King himself. The circumstances have been described above, in the Sigāla Birth (Jātaka 156).

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was the King of Benares, the Bodhisatta was born as the son of a brahmin in Kāsi. On his nameday they called him “Master Tirīṭavaceha.” In due time he grew up, and he studied at Takkasilā University. He married and settled down, but when his parents dies he was so distressed that he became a recluse. He lived in a woodland hut feeding on the roots and fruits of the forest.

While he was living there, there was an attack on the frontiers of Benares. The King went there, but his army was defeated in a battle. Fearing for his life, he mounted an elephant and fled away covertly through the forest.

In the morning, Tirīṭavaceha went out to gather wild fruit, and the King came upon his hut. “A hermit’s hut” he said. He got down from his elephant, weary from the wind and the sun, and he was very thirsty. He looked around for a waterpot, but he could not find one. At the end of the covered walk he saw a well, but he did not see a rope and bucket in which to draw water. But his thirst was too great to bear. So he took off the harness from the elephant, fastened it to the edge of the well, and lowered himself down. But it was too short, so he tied his lower garment on to the end of the harness and lowered himself down again. But he still could not reach the water. He could only touch it with his feet, and he was very thirsty!

“If I can just satisfy my thirst,” he thought, “death itself will be sweet!”

So he let go of his support and dropped into the well. He drank his fill, but now he could not back get up again. So he remained there standing in the well. And the elephant, who was so well trained, stood still, waiting for the King.

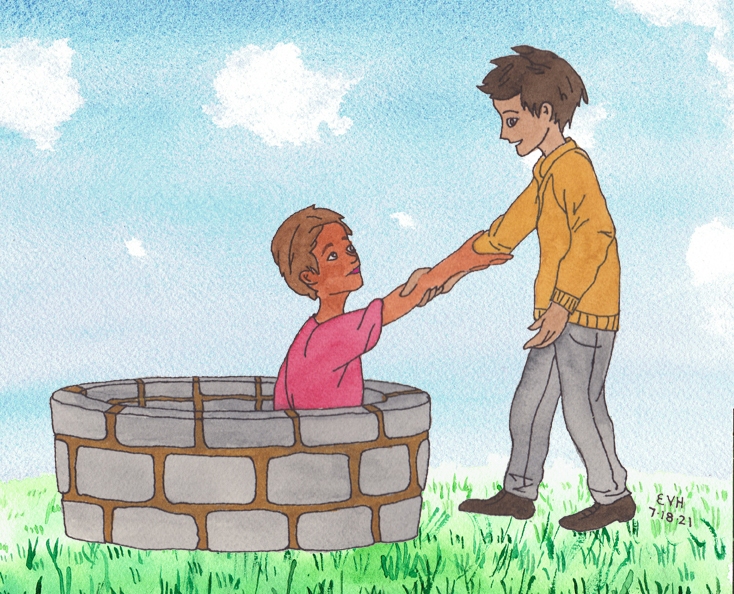

In the evening, the Bodhisatta returned. He was laden with wild fruits, and he saw the elephant. “I presume,” he thought, “the King is here, but the only thing I see is his armed elephant. What should I do?” So he walked over to the elephant who obediently stood and waited for him. He went to the edge of the well and saw the King at the bottom. “Fear nothing, Oh King!” he called out. Then he lowered a ladder into the well and helped the King out. He massaged the King’s body and rubbed him with oil. Then he gave him fruits to eat and loosed the elephant’s armor. The King rested there for several days. Then he left after making the Bodhisatta promise to pay him a visit.

Figure: A simple act of kindness

When the King got back to the city, the royal forces were camped there. When they saw the King coming, they rushed out to greet him.

After six weeks passed, the Bodhisatta returned to Benares and settled in the park. On the next day he went to the palace to ask for food. The King had opened a great window. He stood looking out into the courtyard. Seeing the Bodhisatta and recognizing him, he went out to greet him. He led him to a platform and set him on the throne under a white umbrella (the symbol of royal authority). He gave him his own food to eat and ate some of it himself. Then he took him to the garden. He had a covered walk and a hut built for him. He furnished him with all the necessities of a recluse. Then he put him under the care of a gardener, said his farewells, and left. After this, the Bodhisatta took his food in the King’s own dwelling, and he was treated with great respect and honor.

But the King’s courtiers were very annoyed by all this. “If a soldier,” they said, “were to receive such honor, how would he behave!” They went to the viceroy and said “My lord, our King is making too much of a recluse! What does he see in this man? You speak to the King about it.” The viceroy agreed. They all went together before the King. The viceroy greeted the King and uttered the first stanza:

“There is no wit in him that I can see.

He is no kinsman, nor a friend of thee.

Why should this hermit with three bits of wood,

Tirīṭavaceha, have such splendid food?”

(The “three bits of wood” refers to having a place on which to hang a waterpot.)

The King listened. He addressed his response to his son.

“My son, do you remember how once I went to war and how I was defeated and did not come back for days?”

“I remember,” he said.

“This man saved my life,” the King said. He told him everything that had happened. “Well, my son, now my savior is with me. I can never fully repay him for what he has done, not even if I were to give him my kingdom.” And he recited the following two stanzas:

“When all alone, in a grim thirsty wood,

He, and no other, tried to do me good,

In my distress he lent a helping hand,

Half-dead he drew me up and made me stand.

“By his sole doing I returned again

Out of death’s jaws back to the world of men.

To compensate such kindness is but fair,

Give a rich offering, nor stint his share.”

So the King proclaimed as though he were causing the moon to rise up in the sky. And as he pronounced the virtue of the Bodhisatta, so his virtue was spread everywhere. His reputation increased and he was shown great honor. After that neither the viceroy nor the courtiers nor anyone else dared say anything against him to the King. The King lived gratefully in the Bodhisatta’s debt. He gave alms and did good deeds, and when his life came to an end he went to swell the hosts of heaven. And the Bodhisatta, having cultivated the Perfections and the Attainments, became destined to be reborn the world of Brahma.

Then the Master added, “Wise men of old gave help too.” And having concluded his discourse, he identified the birth as follows: “Ānanda was the King, and I was the recluse.”