Jataka 279

Satapatta Jātaka

The Crane

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story requires a little background about the main subjects. These are Paṇḍuk, Lohita, Assaji, Punabbasu, Paṇḍuka, and Lohita. According to the texts, they were unable to earn a living in lay life so they joined the Saṇgha as a means of support. They were all from Sāvatthi and they all knew each other. After they ordained, they split into three groups of two in the order just given. They are frequently mentioned as monks who broke the monastic rules. In particular they were known for causing discord in the Saṇgha. Their followers were known as the “Chabbaggiyas.”

There are some interesting points in this story. First, the Buddha-to-be is a robber here. This shows that even beings with a great deal of good karma can have an unfortunate rebirth. This is because all unenlightened beings have both good and bad karma, and the bad karma can manifest at the time of rebirth.

Second, the rebirth of the mother as a jackal is what is known in the Dharma as “spontaneous rebirth.” This means rebirth without going through a pregnancy. Belief in spontaneous rebirth is part of right view according to the Buddha. And “confirmed confidence” in right view—including spontaneous rebirth—is one of the requisite factors in stream-entry.

The theme—as summarized in the original translators’ capping poem—is to be able to recognize who your true friend is. As the Buddha often said, a poor friend is often worse than an enemy.

“As the youth upon his way.” The Master told this story when he was at Jetavana. It is about Paṇḍuka and Lohita. Of the Six Dissidents, two—Mettiya and Bhummaja—lived in Rājagaha. Two—Assaji and Punabbasu—lived in Kīṭāgiri. And the two others—Paṇduka and Lohita—lived at Jetavana near Sāvatthi. They questioned matters described in the Dharma. They encouraged their friends and supporters by saying, “You are just as good, brother, in birth, lineage, or character. But if you give up your opinions, they will think they are superior to you.” And by saying this kind of thing they remained attached to their opinions, and arguments and quarrels and contentions arose. The monks told this to the Blessed One. The Blessed One assembled the Saṇgha for this purpose to explain. He had Paṇḍuka and Lohita summoned and addressed them, saying, “Is it true, monks, that you question certain aspects of the Dharma and prevent people from giving up their opinions?” “Yes,” they replied. “Then,” he said, “your behavior is like that of the Man and the Crane.” And he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born into a family in a Kāsi village. When he grew up, instead of earning a living by farming or trade, he organized a group of 500 robbers. He became their chief, and he lived by highway robbery and breaking into homes.

Now it so happened that a landowner had loaned a thousand gold coins to someone, but he died before receiving it back again. Sometime later, his wife lay on her deathbed. She addressed her son, saying, “Son, your father loaned a thousand gold coins to a man, but he died without getting it back. If I die too, he will not give it to you. Go, while I am still living. Go find him and have him give it back.”

So the son went to get the money.

While the son was away on his mission, the mother died. But the son did not know this. But she loved her son so much that she suddenly reappeared as a jackal on the road on which he was traveling. At the same time, the robber chief with his band lay by the road in wait to plunder travelers. And when her son got to the entrance of the woods, the jackal returned again and again, saying to him, “My son, don’t enter the woods! There are robbers there who will kill you and take your money!”

But the man did not understand what she meant. “Bad luck!” he said. “Here's a jackal trying to stop me!” And he drove her off with sticks and rocks and into the woods he went.

Then a crane flew towards the robbers, crying out, “Here’s a man with a thousand gold coins in his hand! Kill him and take them!” The young fellow did not know what it was doing, so he thought, “Good luck! Here is a lucky bird! Now there is a good omen for me!” He saluted respectfully, crying, “Give voice, give voice, my lord!”

The Bodhisatta, who knew the meaning of all these sounds, observed what these two did, and he thought, “That jackal must be the man’s mother, so she is trying to stop him by telling him that he will be killed and robbed. But the crane must be some enemy, and that is why it says ‘Kill him and take the money.’ And the man does not understand what is happening. He drives off his mother, who wishes for his welfare, while he salutes the crane, who wishes him ill, under the belief that it is a well-wisher. The man is a fool.”

(Now the Bodhisattas, even though they are great beings, sometimes steal by being born as wicked men. This, they say, comes from a fault in their karma.)

So the young man went on, and by and bye he fell in with the robbers. The Bodhisatta caught him, and said “Where do you live?”

“In Benares.”

“Where have you been?”

"There were a thousand gold coins due to me in a certain village, and that is where I have been.”

“Did you get it?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Who sent you?”

“Master, my father is dead, and my mother is ill. It was she who sent me because she thought I would not be able to get it if she were dead.”

“And do you know what has happened to your mother now?”

“No, master.”

"She died after you left, and she loved you so much that she became a jackal in order to protect you. She kept trying to stop you for fear you would be killed. She it was she that you scared away. But the crane was an enemy. He came and told us to kill you and to take your money. You are such a fool that you thought your mother wished you ill when she wished you well. And you thought the crane wished you well when it wished you ill. He did you no good, but your mother was very good to you. Keep your money, and be off!” And he let him go.

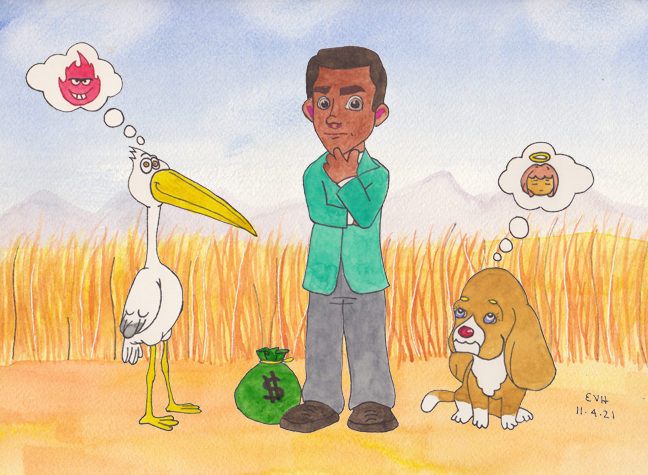

Figure: Know your friends?

When the Master finished this discourse, he repeated the following stanzas:

“As the youth upon his way

Thought the jackal of the wood

Was a foe, his path to stay,

While she tried to do him good:

That false crane his true friend deeming

Which to ruin him was scheming.

“Such another, who is here,

Has his friends misunderstood,

They can never win his ear

Who advise him for his good.

“He believes when others praise—

Awful terrors prophesying:

As the youth of olden days

Loved the crane above him flying.”

After the Master had enlarged upon this theme, he identified the birth, “At that time I was the robber chief.”

(The original translator added this verse as well:

The friend who robs another without ceasing,

He that protests, protests incessantly.

The friend who flatters for the sake of pleasing,

The boon companion in debauchery.

These four the wise as enemies should fear,

And keep aloof, if there be danger near.

)