Jataka 281

Abbhantara Jātaka

The Midmost Mango

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by William Henry Denham Rouse, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a lovely story if you understand the context. The Buddha’s step mother was “Pajapatti.” She was an extraordinary person and one of the most important people in Buddhist history. After the Buddha was born, his biological mother died a week later. Pajapati was also married to his father, the raja of Sakya. She became the Buddha’s mother. She was by all accounts an extraordinarily kind and selfless person. When the Buddha’s father died, the house was empty. Both her son, the Buddha, and her grandson, Rāhula, were monks. So in a famous story, she begged the Buddha to ordain her and 500 other Sakyan women. And this he did.

Meanwhile the Buddha’s wife, Yasodarā, was also left in an empty household. She, too, decided to ordain. So after a fashion the entire family was reunited in the Saṇgha.

Note that Rāhula had Moggallāna as his Dharma teacher and Sāriputta as his preceptor (the monk who instructed him in the Vināya). Ānanda was his uncle, and his father was the Buddha!

Finally, take note of the punchline. Despite extraordinary effort being made on behalf of the Queen, it does not end well.

“There grows a tree.” The Master told this story while he was at Jetavana. It is about the Elder Sāriputta giving mango juice to the Sister Bimbādevī. (This is Yasodarā. Presumably “Bimbādevī” was her Buddhist ordination name.) After the Supreme Buddha inaugurated the sāsana (“Buddha’s dispensation.” This is a period in which a Buddha’s teachings exist.), when he was living in a room at Vesāli, the chief wife of the Gotama (Pajapati) with 500 of the Sākiya clan asked for ordination, and they received full ordination. Afterwards the 500 sisters became arahants on hearing the preaching of Nandaka. And when the Master was living near Sāvatthi, the mother of Rāhula (Yasodarā) thought to herself, “My husband, on embracing the holy life, has become enlightened. My son, too, has become a monk. What am I to do in this empty house? I will enter the holy life. I will go to Sāvatthi, and I will live there looking upon the Supreme Buddha and my son continually.” So she went to a monastery and entered the Saṇgha. She went and lived in a hut at Sāvatthi in the company of her teachers and preceptors. She beheld the Master and her beloved son. Then her son, the novice Rāhula, came to see his mother.

One day, the sister suffered from severe abdominal pain, and when her son came to see her, she could not go to see him. But others went and told him she was ill. Then he went to her hut, and he asked his mother, “What can you take in order to feel better.” “Son,” she said, “at home this pain used to be cured by mango juice flavored with sugar. But now we live by begging, so how can we get it?” The novice said to her, “I’ll get it for you,” and he left.

Now the preceptor of venerable Rāhula was the Captain of the Faith. His teacher was the great Moggallāna. His uncle was the Elder Ānanda, and his father was the Supreme Buddha. So he had great good fortune. However, he went for help to his preceptor, Sāriputta. After greeting him, he stood there with a sad look. “Why do you seem sad, Rāhula?” asked the Elder. “Sir,” he replied, “my mother is ill with abdominal pain.” “What can she take to feel better?” “Mango juice and sugar will cure her.” “All right, I’ll get some. Don’t worry about it.”

So on the next day he took the boy to Sāvatthi. He had him sit in a waiting room while he went up to the palace. The King of Kosala (Pasenadi) asked the Elder to be seated. At that very moment the gardener brought a basket of sweet, ripe mangoes. The King removed the skin, sprinkled sugar on them, crushed them up himself, and filled the Elder’s bowl for him. The Elder returned to the waiting room and gave them to the novice. He asked him to give them to his mother, and this he did. No sooner had the sister eaten then her pain was cured. (Note that Sāriputta was giving up his alms food for that day.)

The King later sent messengers, saying, “The Elder did not sit here to eat the mango juice. Go and find out whether he gave it to anyone.” The messenger went along with the Elder. He found out what was going on and then returned to tell the King. The King thought, “If the Master should be reborn in the human realm, he would be a universal monarch. The novice Rāhula would be his treasure the Crown Prince. The holy sister would be his treasure the Empress, and all the universe would belong to them. I must go and attend upon them. Now they are living nearby so there is no time to be lost.” And from that day on he continually gave mango syrup to the sister.

It became known among the monks how the Elder gave mango syrup to the holy Sister. One day they started talking about it in the Dharma Hall. “Friend, I hear that the Elder Sāriputta comforted Sister Bimbādevī with mango syrup.” The Master came in and asked, “What are you discussing?” When they told him, he said, “This is not the first time, brothers, that Rāhula's mother was comforted with mango syrup provided by the Elder. The same happened before.” And he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born into a brahmin family living in the village of Kāsi. When he grew up, he was educated at Takkasilā University, then he settled down into family life. When his parents died, he embraced the holy life. After that he lived in the Himalaya Mountains, cultivating the Faculties (1) faith/confidence, 2) energy, 3) mindfulness, 4) concentration/samadhi and 5) wisdom/insight) and the Attainments (jhānas). A body of sages gathered round him, and he became their teacher.

After a long time had passed, he came down from the hills to get salt and spices. In the course of his wanderings, he arrived at Benares where he took up residence in a park. Because of the power of their virtue, the palace of Sakka (Lord of the Devas) shook. Sakka reflected on what might be happening. He thought, “I will damage their hut. Then their stay will be disturbed. They will be too distressed to have tranquility of mind. Then I shall be left in peace again.”

As he thought about how to do this, he came up with a plan. “I will enter the chamber of the Chief Queen at the middle watch of the night. I will hover in the air and say, ‘Lady, if you eat a midmost mango (this is meant to be enigmatic), you will conceive a son who shall become a universal monarch.’ She will tell the King, and he will send to the orchard for a mango fruit. I will cause all the fruit to disappear. They will tell the King that there are no mangos left. And when he asks who ate them all, they will accuse the recluses.”

So in the middle watch of the night he appeared in the Queen’s chamber. Hovering in the air, he revealed himself to be a god. And conversing with her, he repeated the first two stanzas:

“There grows a fruit upon a tree,

Men call it ‘Middlemost.’ And be

With child, and eat of it, soon she

Bear one to hold the earth in fee.

“Lady, you are Queen indeed,

The King, your husband, holds you dear.

Get the mango for your need,

And Midmost fruit will bring him here.”

Sakka recited these stanzas to the Queen. He cautioned her to be careful and make no delay. He told her to tell the matter to the King herself. He urged her on, and then he went back to his own place.

On the next day, the Queen lay down pretending to be sick. The King sat on his throne under the white umbrella (the symbol of royal authority) watching some dancing. Not seeing his queen, he asked a handmaid where she was.

“The Queen is sick,” replied the girl.

So the King went to see her. Sitting by her side, he stroked her back and asked, “What is the matter, lady?”

“Nothing,” said she, “but I have a craving for something.”

“What is it you want, lady?” he asked.

“A middle mango, my lord.”

“Where is there such a thing as a middle mango?”

“I don’t know what a middle mango is, but I know that I will die if I don’t get one.”

“All right, we will get you one. Don’t worry about it.”

In this way the King comforted her, and then he went away. He took his seat upon the royal divan and sent for his courtiers. “My Queen has a great craving for a middle mango. What is to be done?” he said.

Someone told him, “A middle mango is one that grows between two others. Send a message to your park to have them find a mango growing between two others. Get its fruit and let us give it to the Queen.” So the King sent men to do his bidding.

But Sakka used his power to make all the fruit disappear as though it had been eaten. The men who came for the mangoes searched through the whole park, and they could not find a single mango. So they went back to the King and told him that there were no mangoes.

“Who has eaten all the mangoes?” asked the King.

“The recluses, my lord.”

“Give the recluses a beating and throw them out of the park!” he commanded. The people heard and obeyed. Sakka’s wish was fulfilled. The Queen lay on and on, longing for the mango.

The King could not think of what to do. He gathered his courtiers and his brahmins and asked them, “Do you know what a middle mango is?”

The brahmins said, “My lord, a middle mango is the portion reserved for the gods. It grows in the Himalaya Mountains in the Golden Cave. So we have heard by tradition.”

“Well, who can go and get it?”

“A human being cannot go. We must send a young parrot.”

At that time there was a fine young parrot in the King’s family. He was as big as the hub of the wheel in the princes’ carriage. He was strong, clever, and full of wisdom. The King sent for this parrot. He said to him, “Dear parrot, I have done a great deal for you. You live in a golden cage. You have sweet grain to eat on a golden dish. You have sugared water to drink. Now there is something I want you to do for me.”

“Speak on, my lord,” said the parrot.

“Son, my Queen has a craving for a middle mango. This mango grows in the Himalaya in the Golden Mountain. It is reserved for the gods. No human being can go there. You must bring the fruit back from there.”

“Very well, my King, I will do this,” said the parrot. Then the King gave him some sweetened grain to eat on a golden plate and sugar water to drink. He anointed him underneath the wings with oil that had been refined 100 times. Then he took him in both hands, stood at the window, and let him fly away.

The parrot, on the King’s errand, flew up into the air. He went beyond the world of men until he came to some parrots who lived in the first hill region of the Himalaya Mountains. “Where is the middle mango?” he asked them. “Tell me where I can find them.”

“We do not know,” they said, “but the parrots in the second range of hills will know.”

The parrot listened and flew away to the second range. After that he went on to the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth. There, too, the parrots said, “We do not know, but those in the seventh range will know.” So he went there and asked where the middle mango tree grew.

“In such and such a place on the Golden Hill,” they said.

“I have come for the fruit of it,” he said. “Guide me there and help me to collect the fruit.”

“That is the fruit of the King Vessavaṇa (one of the four heavenly kings). It is impossible to get near it. The whole tree from the roots upwards is encircled with seven iron nets. It is guarded by thousands of millions of Kumbhaṇḍa goblins. (Kumbhaṇḍas are the same as yakkas. They live in one of the lower four realms of the Buddhist cosmology.) if they see anyone, he’s done for. The place is like the fire of the dissolution and the fire of hell. Do not ask such a thing!”

“If you will not go with me, then describe the place to me,” he said.

So they told him to go by such and such a way. He listened carefully to their instructions. He did not show himself by day, but at the dead of night, when the goblins were asleep, he approached the tree. He began to softly climb on one of its roots when suddenly the iron net went clink! The goblins woke up. When they saw the parrot, they seized him, crying, “Thief!” Then they discussed what to do with him.

One of them said, “I’ll throw him into my mouth and swallow him!”

Another one said, “I’ll crush him and knead him in my hands and scatter him in bits!”

A third one said, “I’ll split him in two, cook him on the coals, and eat him!”

The parrot heard them deliberating. But without any fear he addressed them. “I say, goblins, who rules over you?”

“We belong to King Vessavaṇa.”

“Well, you have one king for your master, and I have another for mine. The King of Benares sent me here to fetch a fruit of the middle mango tree. Then and there I gave my life to my King, and here I am. He who loses his life for parents or master is born at once in heaven. Therefore I shall pass at once from this animal form to the world of the gods!” and he repeated the third stanza:

“Whatever be the place which they attain

Who, by heroic self-forgetfulness,

Strive with all zeal a master’s end to gain—

To that same place I soon shall win access.”

The goblins listened and were impressed in their hearts. “This is a righteous creature,” they said. “We must not kill him. Let him go!” So they let him go and said, “I say, parrot, you’re free! Go unharmed out of our hands!”

“Do not let me return empty-handed,” said the parrot. “Give me a fruit off the tree!”

“Parrot,” they said, “it is not our right to give you fruit off this tree. All the fruit on this tree is marked. If there is one fruit missing then we will lose our lives. If Vessavaṇa is angry and looks but once, a thousand goblins are broken up and scattered like parched peas hopping about on a hot plate. So we cannot give you any. But we will tell you a place where you can get some.”

“I do not care who gives it,” said the parrot. “But I must have the fruit. Tell me where I may get it.”

“In one of the tortuous paths of the Golden Mountain lives a recluse. His name is Jotirasa. He watches over the sacred fire in a leaf-thatched hut called Kañcana-patti or Goldleaf. It is a favorite of Vessavaṇa. Vessavaṇa constantly sends him four fruits from the tree. Go to him.”

The parrot took his leave and went to see the recluse. He greeted him and sat down on one side. The recluse asked him, “Where have you come from?” “From the King of Benares.” “Why are you here?”

“Master, our Queen has a great craving for the fruit of the middle mango, and that is why I am come. However, the goblins would not give me any, and they sent me to you.”

“Sit down, then, and you shall have one,” said the recluse. Then the four fruits which Vessavaṇa sent arrived. The recluse ate two of them. He gave one to the parrot to eat. And when this was eaten he hung the fourth by a string around the parrot’s neck. Then he let him go. “Off with you, now!” he said. The parrot flew back and gave it to the Queen. She ate it and satisfied her craving. But still—all the same—she did not have a son.

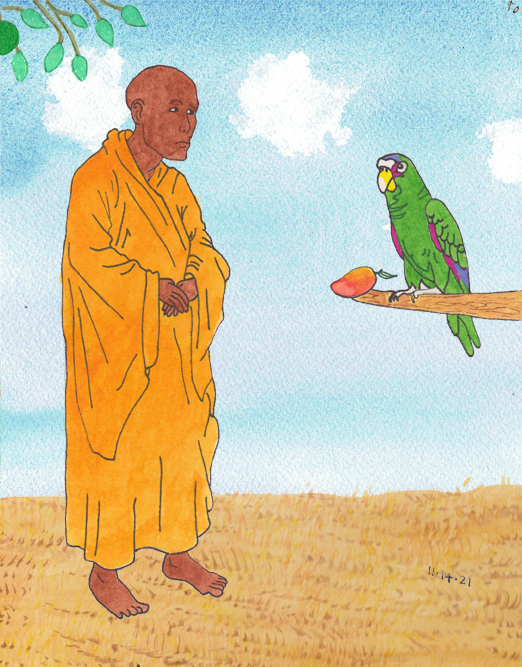

Figure: The generous recluse and the noble parrot

When the Master had ended this discourse, he identified the birth in these words: “At that time Rāhula’s mother was the Queen, Ānanda was the parrot, Sāriputta was the recluse who gave the mango fruit, and I was the recluse who lived in the park.”