Jataka 301

Cullakāliṇga Jātaka

The Weaker Country

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story might also be called, “Whenever you hear a prophecy, make sure you read the fine print.”

“Open the gate.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about the admission of four female recluses to the holy life.

Tradition says that Licchavis of the ruling family to the number of 7,707 had their abode at Vesālī. (The Licchavis were the ruling family of the Indian Republic of Vesāli. Every year these 7,707 “rajas” met together to elect a leader.) And all of them liked to argument and debate.

Now a certain Jain who was skilled in expounding 500 different doctrines arrived at Vesālī and met with a kind reception there. A female Jain who was of a similar character also came to Vesālī. And the Licchavi chiefs initiated a debate between them. And when they proved well matched as disputants, the Licchavis were struck with the notion that such a pair would be sure to have clever children. So they arranged a marriage between them, and as the issue of this union in due course four daughters and a son were born.

The daughters were named Saccā, Lolā, Avavādakā, and Paṭācārā, and the boy was called Saccaka. These five children—when they reached the age of discretion—learned a thousand different doctrines. 500 of these came from the mother and 500 came from the father. And the parents instructed their daughters in this manner: “If any layman refutes your thesis, you are to become his wives, but if a spiritual leader refutes you, you must take orders at his hands.”

After a time their parents died. And when they were dead, the Jain Saccaka lived on in the same place at Vesālī, studying the lore of the Licchavis. But his sisters took in their hands a branch of a rose apple tree, and in the course of their wanderings from city to city for purposes of debate, at last reached Sāvatthi. There they planted the rose apple branch at the city gate and said to some boys who were there, “If any man, be he layman or holy man, is equal to maintaining a thesis against us, let him scatter this heap of dust with his foot and trample this branch under his foot.” And with these words they went into the city to collect alms.

Now the venerable Sāriputta, after sweeping up wherever this was necessary and putting water into the empty pots and tending the sick, went into Sāvatthi for alms later on in the day. And when he had seen and heard about the bough, he ordered the boys to throw it down and trample it. “Let those,” he said, “by whom this bough has been planted, as soon as they have finished their meal, come and see me in the gable chamber over the gate of Jetavana.”

So he went into the city, and when he had ended his meal, he took his place in the chamber over the monastery gate. The female Jains, too, after going on their rounds for alms, returned and found the branch had been trampled on. And when they asked who had done this, the boys told them it was Sāriputta, and if they were anxious for a debate, they were to go to the chamber over the gate of the monastery.

So they returned to the city, and followed by a great crowd went to the gate tower of the monastery. They expounded to the great disciple a thousand different theses. The priest refuted all their doctrines and then asked them if they knew any more.

They replied, “No, my Lord.”

“Then I,” said he, “will ask you something.”

“Ask on, my Lord,” they said, “and if we know it, we will answer you.”

So Sāriputta put just one question to them, and when they could not respond, he told them the answer.

Then said they, “We are beaten, the victory rests with you.”

“What will you do now?” he asked.

“Our parents,” they replied, “instructed us in this way: ‘If you are refuted in debate by a layman, you are to become his wives, but if by a holy man, you are to receive orders at his hands.’” “Therefore,” they they said, “admit us to the Saṇgha.”

Sāriputta readily agreed and ordained them in the house of the nun Uppalavaṇṇā. (Uppalavaṇṇā and Khema were the Buddha’s two chief female disciples.) And all of them shortly became arahants.

Then one day they discussed this in the Dharma Hall, how Sāriputta proved to be a refuge to the four female Jains, and that through him they all became arahants. When the Master came and heard the nature of their discussion, he said, “Not only now, but in former times, too, Sāriputta proved to be a refuge to these women. On this occasion he brought them to the holy life, but formerly he raised them to the status of queen consort.” Then he told them this story from the past.

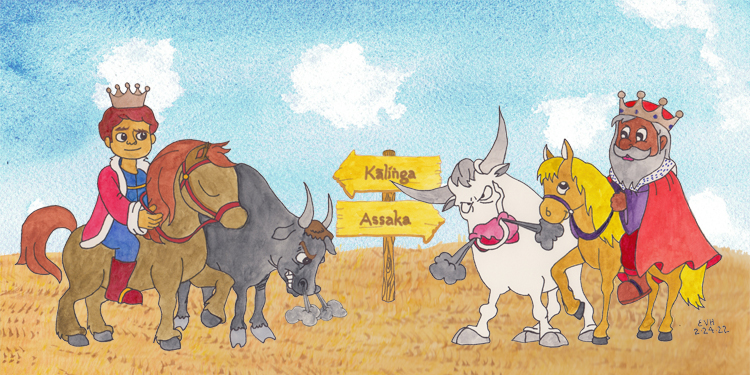

Once upon a time when Kāliṅga was reigning in the city of Dantapura in the Kāliṅga kingdom (on the southeast coast of India), Assaka was the King of Potali in the Assaka country (one of the 16 kingdoms referenced in the Buddhist texts). Now Kāliṅga had a fine army and was himself as strong as an elephant, but he could not find anyone with whom to fight. So being eager for a fray he said to his ministers, “I am longing to fight but can find no one to go to war with me.”

His ministers said, “Sire, there is one way open to you. You have four daughters of unsurpassed beauty. Have them adorn themselves with jewels, and then seat them in a covered carriage. Let them be driven to every village, town, and royal city with an armed escort. And if any king wants to take them into his palace, we will fight with him.”

The King followed their advice. But the kings of the various countries, wherever they came, were afraid to let them enter their cities. Rather they sent them presents and assigned them quarters outside the city walls. And so, in this way, they passed through the length and breadth of India until they reached Potali in the Assaka country. But Assaka, too, closed his gates against them and merely sent them a present.

Now this King had a wise and able minister named Nandisena. He was an expert in forming agreements and resolving disputes. He thought to himself, “These princesses, men say, have travelled the length of India without finding anyone who wants to fight for their possession. If this is the case, India is but an empty name. I myself will do battle with Kāliṅga.”

Then he went and ordered the guards to open the city gate to them, and he spoke the first stanza:

Open the gate to these maidens, through Nandisena’s might,

King Aruna’s sage lion, our city is guarded aright.

(Aruna was the real name of the Assaka King.)

With these words Nandisena threw open the gate and brought the maidens into the presence of King Assaka. He said to him, “Fear not. If there is to be a fight, I will handle it. Make these fair princesses your chief queens.” Then he installed them as queens by sprinkling them with holy water. He dismissed their attendants, telling them to go and tell Kāliṅga that his daughters had been raised to the dignity of queen consorts. So they went and told him, and Kāliṅga said, “I presume he does not know how powerful I am.” He set out at once with a great army. Nandisena heard of his approach and sent a message to this effect: “Let Kāliṅga stay within his own kingdom and not encroach upon ours. The battle will be fought on the frontiers of the two countries.” On receiving this message, Kāliṅga halted within the limits of his own territory, and Assaka also kept to his.

At this time the Bodhisatta was following the holy life and was living in a hermitage on a spot lying between the two kingdoms. Kāliṅga said, “These recluses are wise fellows. Who can tell which of us will gain the victory and which will be defeated? I will ask this recluse.” So he went to the Bodhisatta in disguise, and sitting respectfully on one side, after the usual kindly greetings he said, “Your Reverence, Kāliṅga and Assaka have their armies drawn up each within his own territory, eager for a fight. Which of them will be victorious, and which will be defeated?”

“Your Excellency,” he replied, “one will conquer, the other will be beaten. I can tell you no more. But Sakka, the King of Heaven, is coming here. I will ask him and let you know if you come back again tomorrow.”

So when Sakka came to pay his respects to the Bodhisatta, he put this question to him. Sakka replied, “Reverend Sir, Kāliṅga will conquer, Assaka will be defeated, but certain omens must be seen beforehand.” On the next day Kāliṅga came and repeated his question, and the Bodhisatta gave him Sakka’s answer. And Kāliṅga, without asking what the omens would be, thought to himself, “They tell me that I will conquer,” and he went away quite satisfied.

This report spread abroad. And when Assaka heard it, he summoned Nandisena and said, “Kāliṅga, they say, will be victorious and we will be defeated. What is to be done?”

“Sire,” he replied, “who knows this? Do not trouble yourself as to who will gain the victory and who will suffer defeat.”

With these words he comforted the King. Then he went and saluted the Bodhisatta, and sitting respectfully on one side he asked, “Who, Reverend Sir, will conquer, and who will be defeated?”

“Kāliṅga,” he replied, “will win the day and Assaka will be beaten.” “And what, Reverend Sir,” he asked, “will be the omen for the one that conquers, and what for the one who is defeated.”

“Your Excellency,” he answered, “the tutelary deity of the conqueror will be a spotless white bull, and that of the other king a perfectly black bull. The tutelary gods of the two kings will fight each other and be victorious or defeated.”

(A “tutelary deity” is like a patron saint.)

On hearing this Nandisena rose up and went and took the King’s allies—they were about 1,000 in number and all of them great warriors—and led them up a mountain close at hand. He asked them, “Would you sacrifice your lives for our King?”

“Yes, sir, we would,” they answered.

“Then throw yourselves from this precipice,” he said.

They started to do so, but he stopped them, saying, “No more of this. Show yourselves to be staunch friends of our King and make a gallant fight for him.”

They all vowed to do so. And when the battle was imminent, Kāliṅga came to the conclusion in his own mind that he would be victorious. His army thought so, too, saying, “The victory will be ours.” And so they put on their armor, formed themselves into separate detachments, and advanced just as they thought proper. But when the moment came for the attack, they failed to do so.

But both the Kings, mounted on horseback, drew near to one another with the intention of fighting. And their two tutelary gods moved before them. That of Kāliṅga was in the shape of a white bull, and that of the other King as a black bull. And as they drew near to one another, they made every demonstration of fighting. But these two bulls were visible to the two Kings only and to no one else. And Nandisena asked Assaka, saying, “Your Highness, are the tutelary gods visible to you?”

“Yes,” he answered, “they are.”

“What is their appearance?” he asked.

“The guardian god of Kāliṅga appears in the shape of a white bull, while ours is in the form of a black bull, and he looks distressed.”

“Fear not, Sire. We will conquer and Kāliṅga will be defeated. Dismount from your well-trained Sindh horse, grasp this spear, and with your left hand give him a blow on the flank. Then with this army of a thousand men advance quickly and with a stroke of your weapon strike to the ground this god of Kāliṅga. With a thousand spears we will kill him. Kāliṅga’s tutelary deity will die, and then Kāliṅga will be defeated and we will be victorious.”

“Good,” said the King.

But at a given signal, Nandisena struck with his spear and his courtiers, too, attacked with their thousand spears, and the tutelary god of Kāliṅga died then and there.

Figure: Read the prophesy fine print

So King Kāliṅga was defeated and fled. And at this sight all his thousand soldiers raised a loud cry, saying, “Kāliṅga has fled.” Then Kāliṅga, with the fear of death upon him, as he fled, reproached that recluse and uttered the second stanza:

“Kāliṅgas bold shall victory claim,

Defeat crowns Assakas with shame.

Thus did your reverence prophesy,

And honest folk should never lie.”

Thus did Kāliṅga, as he fled, revile that recluse. And in his flight to his own city he dared not so much as once look back.

A few days later Sakka came to visit the recluse. And the recluse conversed with him uttering the third stanza:

The gods from lying words are free,

Truth should their chiefest treasure be.

In this, great Sakka,you did lie,

Tell me, I pray, the reason why.

On hearing this, Sakka spoke the fourth stanza:

Have you, O brahmin, never been told

Gods envy not the hero bold?

The fixed resolve that may not yield,

Intrepid prowess in the field,

High courage and adventurous might

For Assaka did win the fight.

And on the flight of Kāliṅga, King Assaka returned with his spoils to his own city. And Nandisena sent a message to Kāliṅga that he was to send a dowry for these four royal maidens. “Otherwise,” he added, “I will know how to deal with you.” And Kāliṅga, on hearing this message, was so alarmed that he sent a fitting dowry for them. And from that day forward the two Kings lived amicably together.

When the Master ended this discourse, which he began for the purpose of giving a lesson to the King of Kosala, he identified the birth: “Moggallāna was the driver of King Mallika. Ānanda was the King. Sāriputta was the driver of the King of Benares, and I was the King.”