Jataka 307

Palāsa Jātaka

The Tree Spirit

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

We have already seen stories which the kindness and dedication of the Buddha’s attendant Ananda. And we have also seen that Ānanda was—during the Buddha’s life—a stream-enterer but not an arahant. Thus Ānanda still suffered from emotions, particularly when someone he loved passed away. In this story Ānanda is mourning the imminent death of the Buddha. Perhaps more importantly he makes the mis-statement that his service to the Buddha was “fruitless.” But the Buddha tells him that his service earned him great merit, and that cannot be taken away from him.

This story seems a little hard to believe given that Ānanda was the Buddha’s attendant for 25 years, and one would think that during all that time Ānanda would know that the merit gained from kindness cannot be taken away. Nonetheless, the lesson is an important one. Our lives should be dedicated to developing good qualities, doing good deeds, and to the attainment of enlightenment.

And one final note… the story of the Buddha’s death is found in the Mahā-parinibbana Sutta, DN 16. It is quite lengthy, and it is one of the few suttas that is almost entirely biographical.

“Why, brahmin, though…” The Master, when he was laying on his death bed, told this story about the Elder Ānanda.

The venerable Ānanda, knowing that the Master would die that evening as day turned into night, said to himself, “I am still under discipline and have duties to perform, and my Master is certainly going to die, and then the service I have rendered to him for 25 years will be fruitless.” And so, being overwhelmed with sorrow, he leaned upon the monkey-head shaped door bolt of the garden storeroom and burst into tears.

And the Master, missing Ānanda, asked the monks where he was. When he heard what was the matter, he sent for him and addressed him as follows: “Ānanda, you have laid up a store of merit. Continue to strive earnestly and you will soon be free from human passion. Do not grieve. How can the service you have given me prove fruitless now, seeing that your past services were not without their reward? Then he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta reigned in Benares, the Bodhisatta was reborn in the form of a Judas-tree (Cercis siliquastrum) sprite. Now at this time all the inhabitants of Benares were devoted to the worship of various deities, and they were constantly engaged in religious offerings and the like.

And a certain poor brahmin thought, “I, too, will watch over some deity.” So he found a big Judas-tree growing on high ground, and by sprinkling gravel and sweeping all around it, he kept its roots smooth and free from grass. Then he presented it with a scented wreath of five scents and—lighting a lamp—he made an offering of flowers and perfume and incense. And after a reverential salutation he said, “Peace be with you,” and then he went on his way.

On the next day he came quite early and asked about its welfare. Now one day it occurred to the tree-sprite, “This brahmin is very attentive to me. I will test him and find out why he pays homage to me, and then I will grant him his desire.”

So when the brahmin came and was sweeping around the root of the tree, the spirit stood near him disguised as an aged brahmin, and he repeated the first stanza:

Why, brahmin, though you are with reason blessed,

Have you this dull unfeeling tree addressed?

Vain is your prayer, your kindly greeting vain,

From this dull wood no answer will you gain.

On hearing this the brahmin replied in a second stanza:

Long on this spot a famous tree has stood,

A dwelling place for spirits of the wood.

With deepest awe such beings I revere,

They guard, I think, some sacred treasure here.

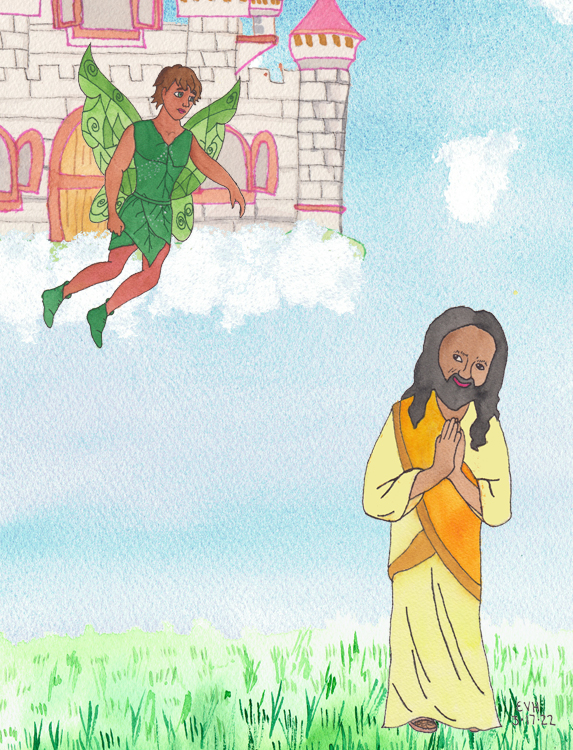

The tree-sprite, on hearing these words, was so pleased with the brahmin that he said, “O brahmin, I was born as the deity of this tree. Fear not. I will grant you this treasure.” And to reassure him, by a great manifestation of divine power, he stood suspended in the air at the entrance of his celestial mansion, while he recited two more stanzas:

O brahmin, I have seen your act of love.

A pious deed can never fruitless prove.

Lo! where that fig-tree casts its ample shade,

Due sacrifice and gifts of old were paid.

Beneath this fig a buried treasure lies,

Unearth the gold, and claim it as your prize.

Figure: It’s good to be good.

The spirit continued, adding these words: “O brahmin, you would become weary if you had to dig up the treasure and carry it away with you. So just go on your way, and I will bring it to your house and deposit it in an appropriate place. Then enjoy it for your whole life, and give alms and keep the Precepts.” And after thus addressing the brahmin, the tree-sprite, by an exercise of divine power, carried the treasure to the brahmin’s house.

The Master here brought his lesson to an end and identified the birth: “At that time Ānanda was the brahmin, and I was the tree-sprite.”