Jataka 321

Kuṭidūsaka Jātaka

The Hut Defiler

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story has a couple of interesting points.

The first is when the Buddha notes that you are better off being alone—living in solitude—than being with fools. There is this famous passage from the Dhammapadda:

If, in your course, you don’t meet

your equal, your better,

then continue your course,

firmly,

alone.

There’s no fellowship with fools. — [Dhp 61]

And I can tell you from hard experience, finding true companions in the Dharma can be extremely difficult.

The second point is an oldie but a goodie, and that is the condemnation of anger. In the Buddha’s teachings, nothing good ever comes from anger. It is a defilement, and something to overcome. We should only act from good qualities: kindness, virtue, love, compassion, wisdom, generosity, gratitude, patience, equanimity, and honesty. This does not mean suppressing our emotions, but learning to make them workable. Overcoming any defilement takes time. It is a skill. And like any skill, it takes time and effort to develop.

The final point I will make is that the ability to accept criticism is important in a disciple of the Buddha. This is how one progresses in the training, in the same way that a skilled craftsperson improves by a teacher’s skilled comments:

“Friends, though a bhikkhu does not ask thus: ‘Let the venerable ones admonish me; I need to be admonished by the venerable ones,’ yet if he is easy to admonish and possesses qualities that make him easy to admonish, if he is patient and takes instruction rightly, then his companions in the holy life think that he should be admonished and instructed, and they think of him as a person to be trusted.” — [MN 15.4]

“Monkey, in feet.” This story was told by the Master while he was living at Jetavana. It is about a young disciple who burned down the hut of leaves of the elder Mahākassapa (one of the principal disciples of the Buddha and the leader of the First Buddhist Council after the Buddha’s death). The incident that led to the story originated in Rājagaha. At that time, they say, the elder was living in a cell in the forest near Rājagaha. Two young novices attended to his needs. One of them was of great service to the elder, but the other one was ill-behaved. Whatever was done by his comrade, he made it look as if he had done it himself. For instance, when the other lad had gotten water to rinse the mouth, he would go to the elder, salute him, and say, “Sir, the water is ready. Please rinse your mouth.” And when his companion had swept out the elder’s cell, as soon as the elder appeared, he acted as if the whole cell had been swept out by himself.

The dutiful disciple thought, “This ill-behaved fellow claims whatever I do just as if he had done it himself. I will expose his cunning behavior.” So when the young rogue had returned from the village and was sleeping after his meal, he heated water for the bath. But he hid it in a back room, and then put merely a small quantity of water in the boiler. The other lad on waking went and saw the steam rising up and thought, “No doubt our friend has heated the water and put it in the bathroom.” So he went to the elder he said, “Sir, the water is in the bathroom. Please, take your bath.” The elder went with him to take a bath. Finding no water in the bathroom, he asked where the water was. The lad went hastily to the heating chamber and put a ladle into the empty boiler. The ladle struck against the bottom of the empty vessel and gave forth a rattling sound. Thereafter the boy was known by the name of "Rattle-Ladle."

At this moment the other lad fetched the water from the back room. He said, “Sir, please take your bath.” The elder had his bath, and now that he was aware of Rattle-Ladle’s misconduct, when the boy came in the evening to wait upon him, he reproached him and said, "When one who is under sacred vows has done a thing himself, then only he has the right to say, “I did that.” Otherwise it is a deliberate lie. From now on do not guilty of conduct like this.”

The boy was angry with the elder, and on the next day he refused to go into the town with him to beg for alms. But the other youth accompanied the elder. And Rattle-Ladle went to see a family of the elder’s benefactors. When they asked where the elder was, he answered that he remained at home ill. They asked what he ought to have. He said, “Give me this and that.” He took it and went to a place that he liked, ate it, and then returned to the hermitage.

On the next day the elder visited that family and sat down with them. The people said, “You are not well, are you? Yesterday, they say, you stayed at home in your cell. We sent you some food by the hand of a lad. Did your reverence enjoy it?” The elder held his peace, and when he had finished his meal, returned to the monastery.

In the evening when the boy came to wait upon him, the elder addressed him in this way: “You went begging, sir, in such and such a family, and in such and such a village. And you begged, saying, ‘The elder must have this to eat.’ And then, they say, you ate it yourself. Such begging is highly improper. See that you are not guilty of such misconduct again.”

So the boy for ever so long nursed a grudge against the elder, thinking, “Yesterday, merely because of a little water, he quarreled with me. And now he is indignant because of my having eaten a handful of rice in the house of his retainers, and he quarrels with me again. I will find out a way to deal with him.”

On the next day, when the elder had gone into the city for alms, he took a hammer and broke all the vessels used for food. He set fire to the hut of leaves and took to his heels. While he was still alive he became a preta (hungry ghost, someone who is never satisfied) in the world of men. He withered away until he died and was born again in the Great Hell of Avīci (the lowest level of the hell realm). And the disgrace of his evil deed spread abroad among the people.

So one day some monks went to Sāvatthi from Rājagaha. And after putting away their bowls and robes in the Common Room, they went to see the Master. After saluting him they sat down. The Master talked pleasantly with them and asked from where they had come. “From Rājagaha, Sir.”

“Who is the teacher there?” he said.

“The Great Kassapa, Sir.”

“Is Kassapa quite well, brothers?” he asked.

“Yes, Reverend Sir, the elder is well. But a young member of the Saṇgha was so angry because of a reproof he gave him that he set fire to the elder’s hut of leaves and made off.”

The Master, on hearing this, said, “Brothers, solitude is better for Kassapa than keeping company with a fool like this.” And so saying he repeated a stanza in the Dhammapada:

To travel with the vulgar herd refuse,

And fellowship with foolish folk eschew,

Your peer or better for a comrade choose

Or else in solitude your way pursue.

Moreover he again addressed the monks and said, “Not only now, brothers, did this youth destroy the hut and feel angry with one that reproved him. In former times too he was angry.” And then he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta reigned in Benares, the Bodhisatta was reborn as a young siṅgila bird (a kind of horned bird). And when he grew to be a big bird, he settled in the Himālaya country. He built a nest to his satisfaction. It offered him protection against the rain.

Then during the rainy season, when the rain fell unceasingly, a certain monkey came up to the Bodhisatta. His teeth chattered because of the severe cold. The Bodhisatta, seeing him distressed, started talking with him. And he uttered the first stanza:

Monkey, with feet and hands and face

So like the human form,

Why not construct a dwelling-place,

To hide you from the storm?

The monkey, on hearing this, replied with a second stanza:

In feet and hands and face, O bird,

Though close to man allied,

Wisdom—chief boon on him conferred,

To me has been denied.

The Bodhisatta, on hearing this, repeated yet two more couplets:

He that inconstancy betrays, a light and fickle mind,

Unstable proved in all his ways, no happiness may find.

Monkey, in virtue to excel, do you your utmost strive,

And safe from wintry blast to dwell, go, hut of leaves contrive.

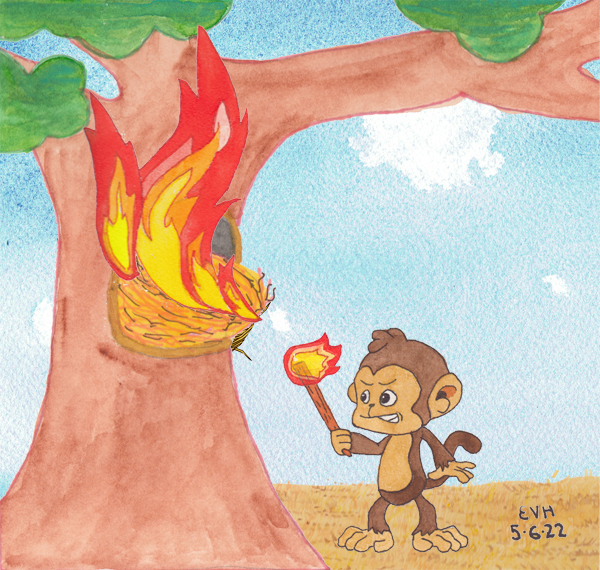

The monkey thought, “This creature, through living in a place that is sheltered from the rain, despises me. I will not let him rest quietly in this nest.” Accordingly, he attacked him. But the Bodhisatta flew up into the air and flew off. And the monkey, after smashing and destroying the nest, took off.

Figure: The mean monkey

The Master, having ended his lesson, identified the birth: “At that time the youth that burned down the hut was the monkey, and I was the siṅgila bird.”