Jataka 353

Dhonasākha Jātaka

The Wise Friend

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story is nominally about karma. Bad deeds bring bad results. But there is also a subtler message here. People wo have certain temperaments—in this case a vile, evil one—will carry those traits from one lifetime into the next. In fact, this is true for all people and all temperaments. The only cure to the endless wandering through saṃsara is to undertake the Buddha’s path of training.

“Though you are now.” The Master told this story while living in the Bhesakalā grove near Suṁsumāragiri (Mount Crocodile) in the country of the Bhaggas. (The Bhagga country lay between Vesāli and Sāvatthī. It was a tribal community.) It is about a young prince Bodhi. This prince was the son of Udena, and he was living in Suṁsumāragiri. Now he summoned a very skillful artisan and got him to build him a palace called “Kokanada.” He had him build it unlike that of any other king. And afterwards he thought, “This artisan may build a similar palace for some other king.” And from envy and jealousy he plucked out his eyes.

This circumstance became known in the assembly of the Saṇgha. They started a discussion in the Dharma Hall, saying, “Sirs, young prince Bodhi had the eyes of an artisan put out. Surely he is a harsh, cruel, and violent man.” The Master came in and asked what they were discussing. When he heard what it was he said, “Not now only, but in the past, too, this was his nature. In the past he put out the eyes of a thousand warriors and, after killing them, he offered up their flesh as a religious sacrifice.” And so saying he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta became a world-renowned teacher at Takkasilā University. The youths of the warrior and brahmin castes came from all over India to be taught the arts by him. The son of the King of Benares did so, too. His son, Prince Brahmadatta, was taught the three Vedas by the Bodhisatta.

Now the Prince was by nature harsh, cruel, and violent. The Bodhisatta, by his supernatural powers, knew his character. He said, “My friend, you are harsh, cruel, and violent, and power that is attained by a man of violence is short-lived. When his power is gone from him, he is like a ship that is wrecked at sea. He reaches no safe haven. Therefore, do not be of such a character.” And by way of admonition he repeated two stanzas:

Though you are now with peace and plenty blessed,

Such happy fate may short-lived prove to be.

Should riches perish, be not so distressed,

Like storm-tossed sailor wrecked far out at sea.

Each one shall fare according to his deed,

And reap the harvest as he sows the seed,

Whether of goodly herb, or some noxious weed.

Then the Prince bade his teacher farewell and returned to Benares. And after exhibiting his proficiency in the arts to his father, he was established as a viceroy. And on his father’s death, he ascended to the throne.

His family priest, Piṅgiya by name, was a harsh and cruel man. Being greedy for fame, he thought, “What if I were to cause all the rulers of India to be seized by this King. Then he would become the sole monarch, and I would be the sole priest?” And he got the King to listen to his words.

So the King marched forth with a great army. He attacked the city of a certain king and took him prisoner. And by attacking each kingdom in turn, he eventually gained sovereignty over all of India. And with a thousand kings in his company, he went to seize upon the kingdom of Takkasilā.

The Bodhisatta fortified the walls of the city and made it impregnable to its enemies. Meanwhile the King of Benares had a canopy set up over him and a curtain thrown round about him at the foot of a big banyan tree on the banks of the Ganges. He had a couch spread out for him and took up his quarters there.

Fighting in the plains of India he had captured a thousand kings, but he failed in his attack on Takkasilā. He asked his priest, “Master, though we have come here with a host of captive kings, we cannot take Takkasilā. What are we to do?”

“Great King,” he answered, “Put out the eyes of the thousand kings. Rip open their bellies, and let us take their flesh and the five sweet substances and make an offering to the guardian deity of this banyan tree. Surround the tree with a ring of blood five inches deep. And then the victory soon will be ours.”

The King readily assented. He concealed mighty wrestlers behind the curtain. One by one he summoned each king, and when the wrestlers had squeezed them in their arms until they had rendered them unconscious, he had their eyes put out. After they were dead, he took the flesh and had their carcasses carried away by the Ganges. Then he made the offering, as described above, and had the drum beaten and went forth to battle.

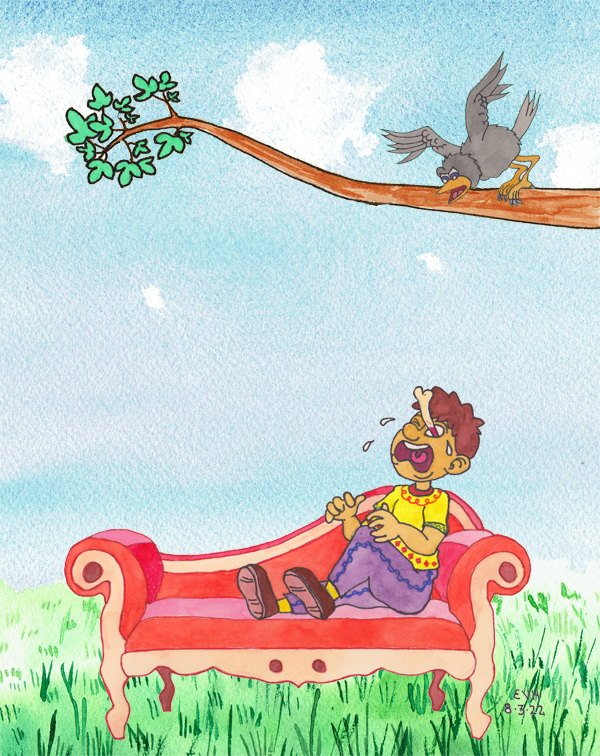

Then a certain Yakkha came from his watch-tower and tore out the right eye of the King. Severe pain set in, and maddened by the agony he suffered, he went and lay down on the couch at the foot of the banyan tree. At this moment a vulture took a sharp-pointed bone, and perched on the top of the tree, it let the bone drop. The sharp point fell like an iron spike on the King’s left eye, destroying that eye, too. At that moment he recalled the words of the Bodhisatta and said, “My teacher, when he said ‘These mortals experience results corresponding to their deeds, even as fruit corresponds with the seed,’ spoke, I suppose, with all this before his mind’s eye.” And in his lamentation he addressed Piṅgiya in two stanzas:

Ah! now at last I recognize the truth

The Master taught me in my heedless youth,

“Sin not,” he cried, “or else the evil deed

To your own punishment may one day lead.”

Beneath this tree’s trim boughs and quivering shade

Offering due of sandal oil was made.

‘Twas here I slew a thousand kings, and lo!

The pangs they suffered then, I now must undergo.

Thus lamenting, he called to mind his Queen-consort, and repeated this stanza:

O Ubbarī, my Queen of swarthy hue,

Lithe as a shoot of fair moringa tree,

That does your limbs with sandal oil bedew,

How should I live, bereft of sight of you?

Death itself would be less grievous than this for me!

(Moringa trees are native to India.)

Figure: Results corresponding to deeds

While he was still murmuring these words, he died and was reborn in hell. The priest who was so ambitious for power could not save him, nor could he save himself by his own power. And as soon as he died, his army broke up and fled.

The Master, having ended his lesson, thus identified the birth: “At that time the young Prince Bodhi was the marauding King. Devadatta was Piṅgiya, and I was the world-renowned teacher.”