Jataka 391

Dhajaviheṭha Jātaka

For the World’s Good

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story highlights one of the recurring themes in Buddhism, and that is the importance of paying homage to noble people. This requires two qualities. The first is the ability to know who is noble, who is worth venerating. The second quality is humility. This is a particularly difficult ability for people in the West. We tend to have a lot of hubris.

“Noble of face.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about his acting for the whole world’s good. The occasion will appear in the Mahākaṇha Birth (Jātaka 469). Then the Master said, “Brothers, this is not the first time the Tathāgata has acted for the world’s good.” And then he told this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was the King in Benares, the Bodhisatta was Sakka. At that time a wizard, using his magic, came at midnight and molested the chief Queen of Benares. Her handmaids knew about this. She went to the King and said, “Your majesty, some man enters the royal chamber at midnight and molests me. Can you help me to make a mark on him?” “I can.” So he gave her a bowl of real vermilion. The man came that night, and as he was leaving after his enjoyment, she put a mark with her five fingers on his back. In the morning she told the King. The King gave orders to his men to go and look everywhere for a man with a vermilion mark on his back.

Now the wizard—after his misconduct at night—would stand all day in a cemetery on one foot worshipping the sun. The King’s men saw him and surrounded him. But he deduced that his action had become known to them. So he used his magic and flew away in the air. When the men returned, the King asked his men, “Did you see him?” “Yes, we saw him.” “Who is he?” “A monk, your majesty.” For after his misconduct at night, he had disguised himself as a monk.

The King thought, “These men go about by day in ascetic’s robes, but then they misconduct themselves at night.” So being angry with the Saṇgha, he adopted immoral views. He sent around a proclamation by drum that all the monks must leave his kingdom and that his men would punish them wherever they were found. All the ascetics fled from the kingdom of Kāsi to other royal cities. As a result, there was no one—righteous Buddhist or Brahmin—to teach the people of Kāsi.

Without guidance, the men became wild and savage. And being averse to generosity and morality, most of them were reborn in a state of punishment when they died. They were never reborn in heaven.

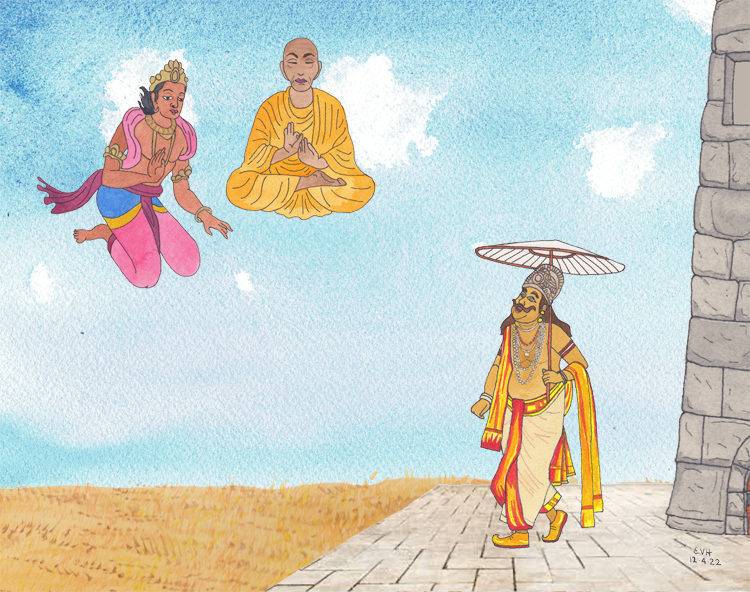

Sakka—on not seeing any new gods—reflected on why that might be. Then he saw that it was because of the expulsion of the Saṇgha by the King of Benares from his anger about the wizard. Then he thought, “Except for me there is no one who can destroy this King’s lack of virtue. I will help the King and his subjects.” So he went to the paccekabuddhas in the Nandamūla cave (where paccekabuddhas lived by tradition) and said, “Sirs, give me an old paccekabuddha. I wish to convert the kingdom of Kāsi.” He got the one who was most senior among them. When he took his bowl and robes, Sakka set him in front of him and followed after, making respectful salutation and venerating the paccekabuddha. Sakka then transformed into a beautiful young monk. The paccekabuddha walked three times around the city from end to end, and then he went to the King’s gate, hovering in the air.

The King’s attendants told him, “Your majesty, there is a beautiful young monk with a priest hovering in the air at the King’s gate.” The King rose from his seat, went to the terrace, and said, “Young monk, why do you, who are beautiful, stand venerating that ugly priest, holding his bowl and robes?” And then he spoke the first stanza:

Noble of face, you make obeisance low,

Behind one mean and poor to sight you go.

Is he your better or your equal, say,

Declare to us your name and his, we pray.

The Sakka answered, “Great King, priests are in the place of teacher, therefore it is not right that I should utter his name. But I will tell you my own name.” (In other words, it is not appropriate to say the name of a teacher). So he spoke the second stanza:

Gods do not tell the lineage and the name

Of saints devout and perfect in the way.

As for myself, my title I proclaim,

Sakka, the lord whom thirty gods obey.

The King—on hearing this—asked in the third stanza what was the benefit of venerating the old man:

He who beholds the saint of perfect merits,

And walks behind him with obeisance low.

I ask, O king of gods, what he inherits,

What blessings will another life bestow?

Sakka replied in the fourth stanza:

He who beholds the saint of perfect merits,

Who walks behind him with obeisance low,

Great praise from men in this world he inherits,

And death to him the path of heaven will show.

The King—hearing Sakka's words—gave up his immoral views, and in delight spoke the fifth stanza:

Oh, fortune’s sun on me today does rise,

Our eyes have seen your majesty divine.

Your saint appears, O Sakka, to our eyes,

And many a virtuous deed will now be mine.

Sakka, hearing him praising his master, spoke the sixth stanza:

Surely ‘tis good to venerate the wise,

To knowledge who their learned thoughts incline,

Now that the saint and I have met your eyes,

O King, let many a virtuous deed be thine.

Hearing this the King spoke the last stanza:

From anger free, with grace in every thought,

I’ll lend an ear whenever strangers sue.

I take thy counsel good, I bring to nought

My pride and serve you, Lord, with homage due.

Having said that, he went down from the terrace, saluted the paccekabuddha, and stood on one side. The paccekabuddha sat cross-legged in the air and said, “Great King, that wizard was no monk. From now on, recognize that the world is not vanity. There are good Buddhists and Brahmins. So give gifts, practice morality, keep the holy days.” Sakka then also used his power to raise up into in the air. He encouraged the townsfolk, “From now on be diligent.” He sent out a proclamation by drum that the Buddhists and Brahmins who had fled should return. Then Sakka and the paccekabuddha went back to their own place. The King stood firm in the admonition and did good deeds.

Figure: Sakka, the paccekabuddha, and the King

After the lesson, the Master taught the Four Noble Truths and identified the birth: “At that time the paccekabuddha attained Nirvāna, the King was Ānanda, and I was Sakka.”