Jataka 407

Mahākapi Jātaka

The Great Monkey

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is another story about a self-sacrificing monkey king. I find this to be a particularly beautiful telling with that theme.

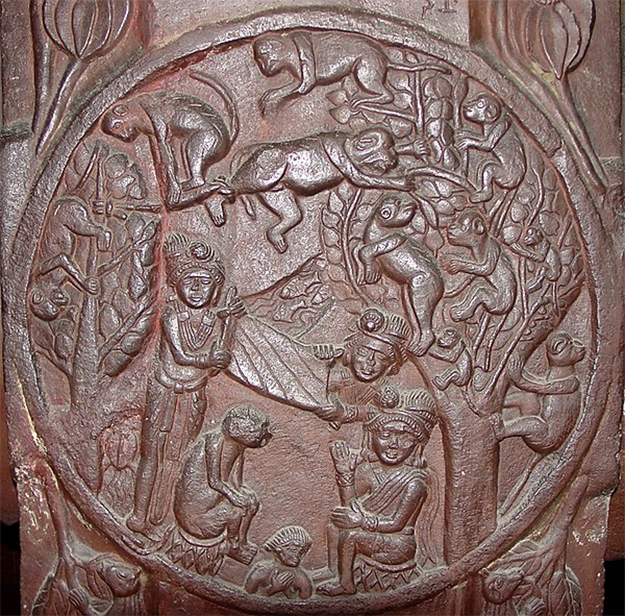

This is one of the Jātaka Tales that is represented on the Bharhut Stūpa in central India.

“You made yourself.” The Master told this story when he was living at Jetavana. It is about good works for one’s relatives. The occasion will appear in the Bhaddasāla Birth (Jātaka 465). They began talking in the Dharma Hall, saying, “The supreme Buddha does good works towards his relatives.” When the Master asked what they were discussing, he said, “Brothers, this is not the first time a Tathāgata has done good works for his relatives.” (“Thatāgatha” is another name for a Buddha.) And then he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born of a monkey’s womb. When he grew up and attained stature and stoutness, he was strong and vigorous. He lived in the Himālaya with a retinue of 80,000 monkeys.

Near the banks of the Ganges there was a mango tree with branches and forks. It provided deep shade and thick leaves like a mountaintop. Its sweet fruits had a divine fragrance and flavor. They were as large as waterpots. From one branch the fruits fell to the ground. From another they fell into the waters of the Ganges. And from two branches the fruits fell into the main trunk of the tree.

One day the Bodhisatta was eating the fruit with a group of monkeys. He thought, “Someday danger will come to us because of the fruit hat falls into the water.” And so, to prevent fruit on the branch that grew over the water from growing, he had them eat or throw down the blossoms from the time they were the size of a chickpea.

But nonetheless, one ripe fruit was unseen by the 80,000 monkeys because it was hidden by an ant’s nest. It fell into the river and stuck in the net that was hanging above the King of Benares. The King was bathing for amusement with a net above him and another below. When the King had enjyed himself all day and was leaving in the evening, the fishermen, who were drawing the net, saw the fruit. Not knowing what it was, they showed it to the King. The King asked, “What is this fruit?” “We do not know, sire.” “Who will know?” “The foresters, sire.”

He had the foresters called, and learning from them that it was a mango, he cut it with a knife. First he had the foresters eat from it. Then he ate some of it himself. Then he had some of it given to his harem and his ministers. The flavor of the ripe mango remained pervading the King’s whole body.

Possessed by his desire of the flavor, he asked the foresters where that tree stood. Hearing that it was on a river bank in the Himālaya, he had many rafts joined together and sailed upstream by the route shown by the foresters. The exact account of days is not given. In due course they came to the place, and the foresters said to the King, “Sire, there is the tree.” The King stopped the rafts and went on foot with a great retinue. He had a bed prepared for him at the foot of the tree. There he lay down after eating the mango fruit and enjoying the various excellent flavors. On each side of him they placed a guard, and then they made a fire.

When the men had fallen asleep, the Bodhisatta arrived at midnight with his retinue. 80,000 monkeys moved from branch to branch eating the mangoes. The King woke up and—seeing the herd of monkeys—roused his men. Calling to his archers, he said, “Surround these monkeys that eat the mangoes so that they may not escape and shoot them. Tomorrow we will eat mangoes with monkey’s flesh!”

The archers obeyed, saying, “Very well.” They surrounded the tree and stood with arrows ready. The monkeys saw them, and fearing death—as they could not escape—went to the Bodhisatta and said, “Sire, the archers stand around the tree, saying, ‘We will shoot those vagrant monkeys.’ What are we to do?” And so the monkeys stood there, shaking with fright.

The Bodhisatta said, “Do not fear. I will save your lives.” And so—comforting the herd of monkeys—he ascended a branch that rose up straight. He moved along another branch that stretched towards the Ganges, and springing from the end of it, he passed a hundred bow lengths. He landed on a bush on the bank (on the far bank). As he descended, he noted the distance, saying, “That will be the distance I have come.” And cutting a bamboo shoot at the root and stripping it, he said, “So much will be fastened to the tree, and so much will stay in the air.” And so he determined the two lengths, forgetting the part that was required to fasten it on his own waist.

Taking the shoot, he fastened one end of it to the tree on the Ganges bank and the other to his own waist. Then he cleared the space of a hundred bow-lengths with the speed of a cloud torn by the wind. But because he had not taken into account the part fastened to his waist, he failed to reach the tree. So he seized a branch firmly with both hands and signaled to the troop of monkeys. “Go quickly with good luck, walking on my back along the bamboo shoot.” And the 80,000 monkeys escaped in this way after saluting the Bodhisatta and getting his leave.

Figure: The monkey king saves his herd.

At that time, Devadatta was a monkey and among that herd. He said, “This is a chance for me to see the last of my enemy.” So he climbed up a branch from which he sprang down and fell on the Bodhisatta’s back. The Bodhisatta’s heart broke and he was in great pain. Devadatta—having caused that maddening pain—then went away, leaving the Bodhisatta alone.

When the King woke up, he saw all that had been done by the monkeys and the Bodhisatta. He lay down, thinking, “This animal, disregarding his own life, has provided for the safety of his troop.” Being pleased with the Bodhisatta, when the day broke, he thought, “It is not right to destroy this king of the monkeys. I will rescue him and take care of him.” So he brought the raft down the Ganges and—building a platform there—he had the Bodhisatta lowered down gently. The King had him clothed with a yellow robe on his back and washed in Ganges water. He gave him sugared water and had his body cleansed and anointed with oil refined a thousand times. Then he put an oiled skin on a bed and had him lie down there. Then he sat down on a low seat (as a sign of respect), and spoke the first stanza:

You made yourself a bridge for them to pass in safety through.

What are you then to them, monkey, and what are they to you?

Hearing him, the Bodhisatta instructing the king spoke the other stanzas:

Victorious King, I guard the herd, I am their lord and chief,

When they were filled with fear of you and stricken sore with grief.

I leapt a hundred times the length of bow outstretched that lies,

When I had bound a bamboo shoot firmly around my thighs.

I reached the tree like thunder-cloud sped by the tempest’s blast.

I lost my strength, but reached a bough. With hands I held it fast.

And as I hung extended there, held fast by shoot and bough,

My monkeys passed across my back and are in safety now.

Therefore I fear no pain of death, bonds do not give me pain.

The happiness of those was won o’er whom I used to reign.

A parable for you, O King, if you the truth would read:

The happiness of kingdom and of army and of steed

And city must be dear to you, if you would rule, indeed.

The Bodhisatta, thus instructing and teaching the King, died.

The King called out to his ministers. He ordered that the monkey king should have funeral rites like a human King. He sent word to the royal harem, saying, “Come to the cemetery as a retinue for the monkey king. Wear red garments, and well-groomed hair, and bring torches in your hands.”

The ministers made a funeral pile with a hundred wagon loads of timber. Having prepared the Bodhisatta’s funeral rites in a royal manner, they took his skull and went to the King. The king had a shrine built at the Bodhisatta's place of birth. Torches were burned there and there were offerings of incense and flowers. He had the skull inlaid with gold and put in front raised on a spear point. Honoring it with incense and flowers, he put it at the King’s gate when he returned to Benares. And having the whole city decked out, he paid honor to it for seven days. Then taking it as a relic and building a shrine, he honored it with incense and garlands all his life. And established in the Bodhisatta’s teaching, he gave alms and did other good deeds. And ruling his kingdom righteously, he became destined for heaven.

After the lesson, the Master taught the Four Noble Truths. Then he identified the birth: “At that time Ānanda was the King, the Saṇgha was monkey’s retinue, and I was the monkey king myself.”

Figure: The The Monkey King relief from the Bharhut Stupa