Jataka 412

Koṭisimbali Jātaka

The Cotton Tree

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

One of the themes that permeates the Buddha’s teaching is how important it is to pay attention to even the smallest defilements. In this story, the simile of a seed is used to show how even a tiny seed can grow and kill a large tree. Compare the size of a redwood tree to its seed, and the simile becomes abundantly clear. So the disciple of the Buddha is warned to heed even the smallest indiscretions.

“I bore with me.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about abandoning defilements. The incident leading to the story will appear in the Paññā Birth (Jātaka 149). On this occasion the Master, perceiving that 500 monks were overcome by sensual desire in the House of the Golden Pavement, gathered the assembly. He said to them, “Brothers, it is right to distrust where distrust is proper. Defilements surround a man just as banyans and such plants grow up around a tree. In this way of old a spirit living in the top of a cotton tree saw a bird voiding the banyan seeds it had eaten among the branches of the cotton tree. She became terrified that this would destroy her home.” And then he told this story from the past.

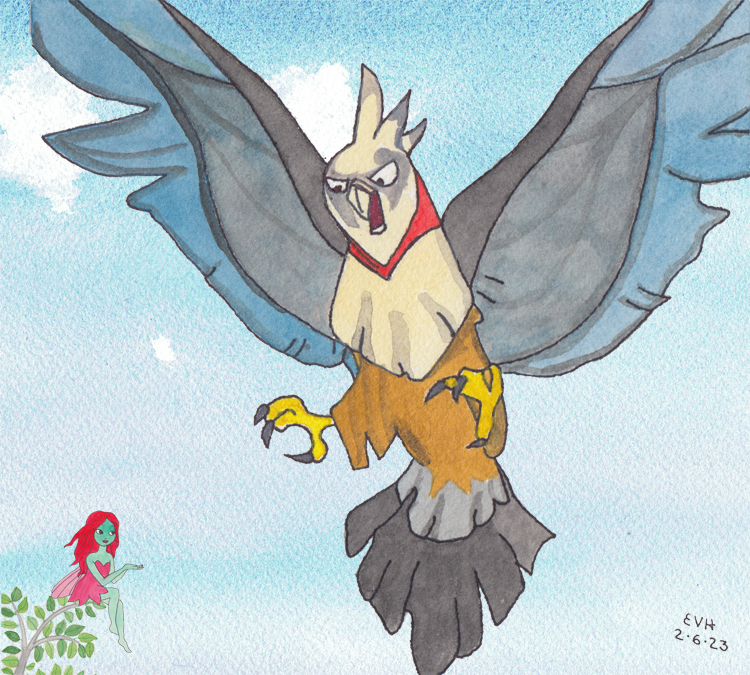

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was a tree spirit who lived in the top of a cotton tree. A king of the rocs (a roc is an enormous mythological bird of prey) assumed a shape 150 leagues long. He divided the water in the great ocean using the blast from his wings. He seized a king of snakes a thousand fathoms long by the tail and made the snake disgorge what he had seized in his mouth. Then he flew away along the tree tops towards the cotton tree. The snake king thought, “I will make him drop me and let me go.” So he stuck his hood into a banyan tree and wound himself firmly around it. Because of the roc king’s strength and the great size of the snake king, the banyan tree was uprooted. Nonetheless, the snake king would not let go of the banyan. The roc king took the snake king—banyan tree and all—to the cotton tree. He laid him on the trunk, opened his belly, and ate the fat. Then he threw the rest of the carcass into the sea.

Now in that banyan tree there was a certain bird who flew off when the banyan was thrown away. He perched in one of the boughs high up in the cotton tree. The tree spirit saw the bird shake and tremble with fear, thinking, “This bird will let its droppings fall on my trunk. A growth of banyan or fig will sprout and spread all over my tree, and my home will be destroyed.” The tree shook to the roots with the trembling of the spirit. The roc king—perceived the trembling—then spoke two stanzas asking why this was happening:

I bore with me the thousand fathoms length of that king snake,

His size and my huge bulk you bore and yet you did not quake.

But now this tiny bird you bear, so small compared to me,

You shake with fear and tremble. But why so, cotton tree?

Figure: “You shake with fear and tremble. But why so, cotton tree?”

Then the spirit spoke four stanzas explaining the reason:

Flesh is your food, O king, the bird’s is fruit.

Seeds of the banyan and the fig he'll shoot,

Bodhi tree too, and all my trunk pollute.

They will grow trees in shelter of my stem,

And I shall be no tree, thus hid by them.

Other trees, once strong of root and rich in branches, plainly show

How the seeds that birds do carry in destruction lay them low.

Parasitic growths will bury e’en the mighty forest tree.

This is why, O king, I quiver when the fear to come I see.

Hearing the tree spirit’s words, the roc king spoke the final stanza:

Fear is right if things are fearful, ‘gainst the coming danger guard,

Wise men look on both worlds calmly if their present fears discard.

So speaking, the roc king by his power drove the bird away from that tree.

After the lesson, the Master taught the Four Noble Truths, beginning with the words, “It is right to distrust where distrust is proper.” After the teaching, the 500 monks became arahants. Then he identified the Birth: “At that time Sāriputta was the roc king, and I was the tree spirit.”