Jataka 415

Kumāsapinda Jātaka

The Righteous Queen

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This Jātaka tells one of the most famous and endearing stories in the Pāli Canon. It is about how the flower girl Mallikā became the chief Queen of the kingdom of Kosala. She is one of the sweetest and kindest people from the Buddha’s time, and as the story tells us, she was a favorite of his.

There is one historical note. The story-in-the-present says that King Pasenadi fought and lost the battle to Ajātasattu. However, Ajātasattu did not become the Kind of Magadha until much later, so it must have been a battle against someone else.

“Service done.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about Queen Mallikā. She was the daughter of the chief of the garland makers of Sāvatthi. She was extremely beautiful and very good. When she was 16 years of age, as she was going to a flower garden with some other girls, she had with her three portions of sour gruel in a flower basket. As she was leaving the town, she saw the Blessed One entering it. He was diffused with radiance and surrounded by the members of the Saṇgha. She gave him the three portions of gruel.

The Master accepted her offering, holding out his royal bowl. She saluted the Tathāgata’s feet with her head, and taking joy as her subject of meditation, she stood on one side. Observing her, the Master smiled. The Venerable Ānanda wondered why the Tathāgata smiled and asked him about this. The Master told him the reason: “Ānanda, this girl will today become the chief Queen of the Kosala King (King Pasenadi) through the fruit of these portions of gruel.”

The girl went on to the flower garden. And on that very day, the Kosala King fought a battle with Ajātasattu and fled away in defeat. As he came by on his horse, he heard the sound of her singing. And being attracted by it, he rode towards the garden. The girl’s merit was ripe, so when she saw the King, she went up to him without running away. She seized the bridle by the horse’s nose. From horseback, the King asked if she was married or not. Hearing that she was not, he dismounted, and being weary from the wind and sun, he rested for a little time in her lap. Then he had her mount, and with his great army he entered the town and brought her to her house.

In the evening he sent a chariot for her, and with great honor and pomp brought her from her house. He gave a heap of jewels to her, anointed her, and made her chief Queen. From that time on she was the dear, beloved, and devoted wife of the King. She had faithful servants and the five feminine charms, and she was a favorite of the Buddhas. It became known abroad and through the whole city that she had attained such prosperity because she had given the three portions of gruel to the Master.

One day they began a discussion in the Dharma Hall. “Sirs, Queen Mallikā gave three portions of gruel to the Buddhas, and as the fruit of that, on the very same day she was anointed Queen. Great indeed is the virtue of Buddhas.” The Master entered the hall. He asked and was told the subject of the brother’s talk. He said, “It is not strange, brothers, that Mallikā has become chief Queen of the Kosala King by giving three portions of gruel to the wise Buddha alone. Why? It is because of the great virtue of Buddhas. Wise men of old gave gruel without salt or oil to paccekabuddhas, and because of that, in their next births they became kings in Kāsi, a region 300 leagues in extent.” And so he told this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born into a poor family. When he grew up, he made a living by working for wages for a certain rich man. One day he got four portions of sour gruel from a shop, thinking, “This will do for my breakfast.” And then he went back to his farm work. Seeing four paccekabuddhas coming towards Benares to collect alms, he thought, “I have these four portions of gruel. What if I were to give them to these men who are coming to Benares for alms?” So he went up to them, and saluting them, he said, “Sirs, I have these four portions of gruel in hand. I offer them to you. Please accept them, good sirs, and then I will gain merit for my lasting good and welfare.” They accepted.

He spread sand and arranged four seats and placed broken branches on them. Then he set the paccekabuddhas in order. He brought water in a leaf basket. He poured water in donation, and then he set the four portions of gruel in four bowls with the salutation and words, “Sirs, in consequence of these may I not be reborn into a poor family. May this be the cause of my attaining wisdom.” The paccekabuddhas ate and then gave thanks, and then they departed to the Nandamūla cave.

The Bodhisatta, as he saluted, felt the joy of associating with paccekabuddhas, and after they left and he had gone back to his work, he remembered them always until his death. As the fruit of his generosity, he was reborn in the womb of the chief Queen of Benares. He was named “Prince Brahmadatta.” From the time of his being able to walk, he saw clearly by the power of recollection all that he had done in former births. It was like the reflection of his face in a clear mirror that he was now born in that state because he had given four portions of gruel to the paccekabuddhas when he was a servant and gone to work in that same city.

When he grew up, he learned all the arts at Takkasilā University. On his return, his father was pleased with the accomplishments he displayed and had him appointed as viceroy. Afterwards, upon the death of his father, he was established in the kingdom. Then he married the exceedingly beautiful daughter of the Kosala King, and he made her his chief Queen. On the day of his parasol festival, they decorated the whole city as if it were a city of the gods. He went around the city in procession. Then he ascended to the palace, which was decorated, and on the dais mounted a throne with the white parasol erected on it. He sat there looking down on all those who stood in attendance. On one side were the ministers, on another were the brahmins and householders, resplendent in the beauty of varied apparel. On another were the townspeople with various gifts in their hands. On another there were troops of dancing girls to the number of 16,000 like a gathering of the nymphs of heaven in full apparel. Looking on all this entrancing splendor, he remembered his former state and thought, “This white parasol with golden garland and base of massive gold, these many thousands of elephants and chariots, my great territory full of jewels and pearls, teeming with wealth and grain of all kinds, these women like the nymphs of heaven, and all this splendor which is mine alone, all this is due solely to an alms gift of four portions of gruel given to four paccekabuddhas. I have gained all this through them.” And so, remembering the excellence of the paccekabuddhas, he plainly declared his own former act of merit. As he thought of it his whole body was filled with delight. Delight melted his heart, and amid the multitude he uttered two stanzas of joyous song:

Service done to Buddhas high

Ne’er, they say, is reckoned cheap.

Alms of gruel, saltless, dry,

Bring me this reward to reap.

Elephant and horse in line,

Gold and corn and all the land,

Troops of girls with form divine,

Alms have brought them to my hand.

So the Bodhisatta in his joy and delight on the day of his parasol ceremony sang the song of joy in two stanzas. From that time onward they were called the King’s favorite song, and everyone sang them—the Bodhisatta’s dancing girls, his other dancers and musicians, his people in the palace, the townsfolk and those in ministerial circles.

After a long time had passed, the chief Queen became anxious to know the meaning of the song, but she was afraid to ask the Great Being. One day the King was pleased with some quality of hers and said, “Lady, I will give you a boon. Accept a boon.” “It is well, O King. I accept.” “What shall I give you, elephants, horses, or the like?” “O King, through your grace I lack nothing. I have no need of such things. But if you wish to give me a boon, tell me the meaning of your song.” “Lady, what need do you have of that boon? Accept something else.” “O King, I have no need of anything else. It is that I will accept.”

"Well, lady, I will tell you, but not as a secret to you alone. I will send a drum around the whole 12 leagues of Benares. I will make a jeweled pavilion at my palace door and arrange a jeweled throne there. On it I will sit amidst the ministers, brahmins, and other people of the city, and the 16,000 women, and there I will tell the tale.” She agreed.

The King arranged everything as he said. Then he sat on the throne amidst the great multitude like Sakka amidst the company of the gods. The Queen, too, with all her ornaments set a golden chair of ceremony and sat in an appropriate place on one side. And looking with a side glance she said, “O King, tell the story and explain to me, as if causing the moon to arise in the sky, the meaning of the song of joy you sing in your delight.” And so she spoke the third stanza:

Glorious and righteous King,

Many a time the song you sing,

In exceeding joy of heart,

Pray to me the cause impart.

The Great Being—declaring the meaning of the song—spoke four stanzas:

This the city, but the station different, in my previous birth,

Servant was I to another, hireling, but of honest worth.

Going from the town to labor four recluses once I saw,

Passionless and calm in bearing, perfect in the moral law.

All my thoughts went to those Buddhas as they sat beneath the tree,

With my hands I brought them gruel, offering of piety.

Such the virtuous deed of merit. Lo! The fruit I reap today.

All the kingly state and riches, all the land beneath my sway.

When she heard the Great Being fully explain the fruit of his action, the Queen said joyfully, “Great King, if you see so visibly the fruits of charitable giving, from this day forward, take a portion of rice and do not eat yourself until you have given it to righteous priests and brahmins.” And then she spoke a stanza in praise of the Bodhisatta:

Eat, due alms remembering,

Set the wheel of right to roll,

Flee injustice, mighty King,

Righteously your realm control.

The Great Being, accepting what she said, spoke a stanza:

Still I make that road my own

Walking in the path of right,

Where the good, fair Queen, have gone,

Saints are pleasant to my sight.

After saying this, he looked at the Queen’s beauty and said, “Fair lady, I have told fully my good deeds done in a former time. But amongst all these ladies there is none like you in beauty or charming grace. By what deed did you attain this beauty?” And he spoke a stanza:

Lady, like a nymph of heaven,

You the crowd of maids outshine,

For what gracious deed was given

Deserved beauty so divine?

Then she told the virtuous deed done in her former birth, and spoke the last two stanzas:

I was once a handmaid’s slave

At Ambaṭṭha’s royal court,

To modesty my heart I gave,

To virtue and to good report.

In a begging brother’s bowl

Once an alms of rice I put.

Charity had filled my soul,

Such the deed, and lo! the fruit.

She, too, it is said, spoke with accurate knowledge and memory of past births.

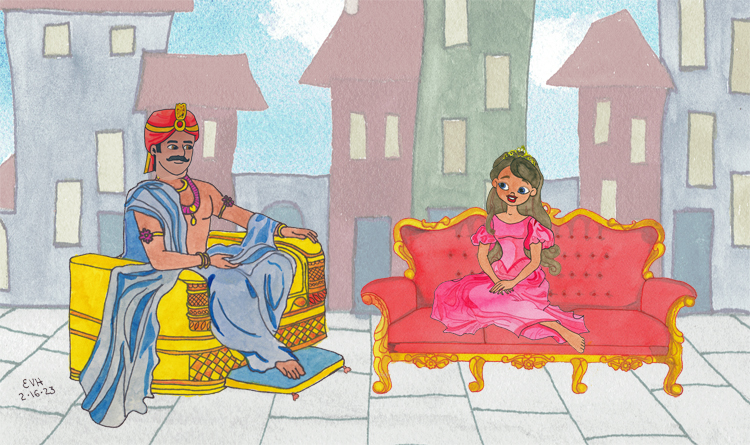

Figure: The Queen explains her act of generosity

So both fully declared their past deeds. And from that day on they had six halls of charity built at the four gates, in the center of the city, and at the palace door. They inspired all India in how they gave great gifts. They kept the moral duties (the Five Precepts) and the holy days, and at the end of their lives, they became destined for heaven.

At the end of the lesson, the Master identified the birth: “At that time the Queen was the mother of Rāhula, and I was the King.”

(The “mother of Rāhula” was Yasodharā, the Buddha’s wife before he became the Buddha.)