Jataka 421

Gaṇgamāla Jātaka

The Barber Gaṇgamāla

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a story about the great merit that comes from even small acts of virtue. It also brings to mind the importance of rebirth in the Buddha’s Dharma.

It is extremely unfortunate that so many Westerners reject the notion of rebirth. For one thing, there is a great deal of scientific evidence that rebirth is true. And further, imagine this. You are a good person. You take the Buddha’s teachings to heart. You act from kindness. You abandon unwholesome qualities like anger. And as a result, instead of having your next life be 80 or so years in the human realm, you spend thousands and perhaps millions of years in a heavenly, deva realm. Your choice.

“The earth is like coals.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about observing the weekly holy days. One day the Master was addressing the lay followers who were observing the holy days, and he said, “Lay followers, your conduct is good. When people observe the holy days, they should give alms, keep the moral precepts, never show anger, feel kindness, and do the duties of the day. Wise people of old gained great glory from even a casual observation of the holy days.” And at their request, he told this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, there was a rich merchant in that city named Suciparivāra. His wealth reached eighty crores (800 million rupees), and he took delight in charity and other good works. His wife and children and his entire household and servants down to the calf herders kept six holy days every month.

(Traditionally in Buddhism followers observe “Uposatha” holy days which fall on the phases of the moon: new, full, and quarter. This family apparently added in a couple more for good measure.)

At that time the Bodhisatta was born into a certain poor family. He lived a hard life on a workman’s wages. Hoping to find work, he went to Suciparivāra’s house. Saluting him and sitting on one side, he was asked his purpose. He said, “It is to find work for wages in your house.” When other workmen came to him, the merchant would say to them, “In this house the workmen keep the moral precepts. If you can keep them, you may work for me.” But to the Bodhisatta he made no mention of the moral precepts. Instead he said, “Very well, my good man. You can work for me and arrange for your wages.”

From then on the Bodhisatta did all the merchant’s work. He did so with humility and enthusiasm, without so much as a thought for his own weariness. He went to work early, and he came back in the evening.

One day they proclaimed a festival in the city. The merchant said to a female servant, “This is a holy day. You must cook some rice for the working people in the morning. They will eat it early and fast the rest of the day.” The Bodhisatta rose early and went about his work. No one told him to fast that day. The other working people ate in the morning and then fasted. The merchant—along with his wife, children and attendants—all fasted. All of them went—each to his own home—and sat there meditating on the moral precepts.

The Bodhisatta worked all day and then went home at sunset. The cook maid gave him water for his hands and offered him a dish of rice taken from the boiler. The Bodhisatta said, “At this hour there is usually a lot of activity on ordinary days. Where has everyone gone today?” “They are all fasting, each in his own home.” He thought, “I will not be the only person misconducting himself among so many people of moral behavior.” So he went and asked the merchant if the fast could be kept by undertaking the duties of the day at that hour. He told him that the whole duty could not be done because it had not been undertaken in the morning, but that half the duty could be done. “So be it,” he answered. And undertaking the duty in his master’s presence, he began to keep the fast. He went to his own home, and there he lay meditating on the precepts.

He had taken no food all day, and in the last watch of the night he felt sharp pains like a spear wound. The merchant brought him various remedies and told him to eat them. But he said, “I will not break my fast. I have undertaken it even if it costs me my life.” The pain became intense and at sunrise he was losing consciousness. They told him he was dying. And taking him outside, they placed him in a quiet place.

At this moment the King of Benares reached that spot in a trip around the city. He was in a noble chariot with a great retinue. The Bodhisatta, seeing the royal splendor, felt a desire for royalty. He prayed for this. As he died, he was conceived again. Because he had kept half the fast day, he was reborn in the womb of the chief Queen. She went through pregnancy, and after ten months, she bore a son.

He was named Prince Udaya. When he grew up, he became proficient in all the sciences. Because of his memory of previous births, he knew about his former action of merit. And thinking it was a great reward for a small action, he sang a song of ecstasy again and again. At his father’s death he took reign over the kingdom. And observing his own great glory, he sang the same song of ecstasy.

One day they prepared for a festival in the city. A great multitude was intent on celebration. A certain water carrier who lived by the north gate of Benares had hidden a half penny in a brick in a boundary wall. He lived with a poor woman who also made her living by carrying water. She said to him, “My lord, there is a festival in the town. If you have any money, let us enjoy ourselves.” “I have, dear.” “How much?” “A half penny.” “Where is it?” “I left my treasure in a brick by the north gate, twelve leagues from here. But have you got anything on hand?” “I have.” “How much?” “A half penny.” “So yours and mine together make a whole penny. We’ll buy a garland with one part of it, perfume with another, and strong drink with a third. Go and get your half penny from where you put it.” He was delighted by his wife’s suggestion, and saying, “Don’t trouble, dear, I will fetch it,” he set out.

The man was as strong as an elephant. He traveled more than six leagues, and even though it was mid-day and he was walking on sand as hot as if it were strewn with coals just off the flame, he was delighted with the thought of pleasure. So in old yellow clothes and with a palm leaf fastened in his ear (the palm leaf is used as an ear ornament), he went by the palace court in pursuit of his purpose, singing a song.

King Udaya was standing at an open window. And seeing him coming, he wondered who it was. The man was disregarding the wind and heat and was singing for joy. So the King sent a servant to call him up. “The King calls for you,” he was told. But he said, “What is the King to me? I don’t know the King.” But he was taken by force and stood on one side of the King. Then the King spoke two stanzas:

The earth’s like coals, the ground like embers hot,

You sing your song, the great heat burns you not.

The sun on high, the sand below are hot,

You sing your song, the great heat burns you not.

Hearing the King’s words, he spoke the third stanza:

‘Tis these desires that burn, and not the sun,

‘Tis all these pressing tasks that must be done.

The King asked what his business was. He answered, “O King, I was living by the south gate with a poor woman. She proposed that she and I should amuse ourselves at the festival and asked if I had any money on hand. I told her I had a treasure stored inside a wall by the north gate. She sent me for it to help us to amuse ourselves. Those words of hers never leave my heart, and as I think of them, great excitement burns in me. That is my business.” “Then what delights you so much that you disregard wind and sun, and you sing as you go?” “O King, I sing to think that when I fetch my treasure I will amuse myself along with her.” “Then, my good man, is your treasure—hidden by the north gate—100,000 gold pieces?” “Oh no.” Then the King asked in succession if it were 50,000, 40, 30, 20, 10, 5, 4, 3, 2 gold pieces, one piece, half a piece, a quarter piece, four pence, three, two, one penny. The man said “No” to all these questions. And then, “It is a half penny. Indeed, O King, that is all my treasure. But I am going in hopes of fetching it and then amusing myself with her. And in that desire and delight the wind and sun do not bother me.”

The King said, “My good man, don’t go there in such heat. I will give you a half penny.” “O King, I will take you at your word and accept it, but I won’t lose the other. I won't give up going there and fetching it, too.” “My good man, stay here. I’ll give you a penny, two pennies.” Then offering more and more he went on to a crore, a hundred crores, then boundless wealth if the man would stay. But he always answered, “O King, I’ll take it, but I’ll fetch the other, too.” Then he was tempted with offers of posts as treasurer and posts of various kinds and the position of viceroy. At last he was offered half the kingdom if he would stay. Finally the man consented. The King said to his ministers, “Go. Have my friend shaved and bathed and adorned. Then bring him back.” They did so. The King divided his kingdom in two and gave him half.

They say that the man obtained the northern half of the kingdom from his love of a half penny, so he was called King Half-penny. The two Kings ruled the kingdom in friendship and harmony. One day they went to the park together. After amusing themselves, King Udaya lay down with his head in King Half-penny’s lap. He fell asleep, and the attendants left to enjoy some amusements. King Half-penny thought, “Why should I only have half the kingdom? I will kill him and be the only king.” So he drew his sword, and as he prepared to strike him, he remembered that the King had made him—when he was poor and mean—his partner. He had given him great power, and the thought that had risen in his mind to kill such a benefactor was a wicked one. So he sheathed the sword.

A second and a third time the same thought rose. Feeling that this thought, rising again and again, would lead him on to the evil deed, he threw the sword on the ground and woke the King. “Pardon me, O King,” he said, and he fell at his feet. “Friend, you have done me no wrong.” “I have, O great King. I had this evil thought.” “Then, friend, I pardon you. If you want it, be the sole King, and I will serve under you as viceroy.” He answered, “O King, I have no need of the kingdom. Such desire will cause me to be reborn in an evil state. The kingdom is yours. Take it. I will become a recluse. I have seen the root of desire. It grows from a man’s craving. From now on I will have no such wishes.” And so in ecstasy he spoke the fourth stanza:

I have seen your roots, Desire. In a man’s mind will they lie.

I will no more wish for you, and you, Desire, will die.

So saying, he spoke the fifth stanza, declaring the Dharma to a great multitude who were devoted to their desires:

Little desire is not enough, and much just brings us pain.

Ah! Foolish men, be sober, friends, if you would wisdom gain.

So declaring the Dharma to the multitude, he entrusted the kingdom to King Udaya. Leaving the weeping multitude with tears on their faces, he went to the Himālaya Mountains. There he became a recluse and attained perfect insight.

When he became a recluse, King Udaya spoke the sixth stanza in complete expression of ecstasy:

Little desire has brought me all the fruit,

Great is the glory Udaya acquires.

Mighty the gain if one is resolute

To be a recluse and forsake desires.

But no one understood the meaning of this stanza. One day the chief Queen asked him the meaning of it, but the King would not explain.

There was a certain court barber. (In those days a barber was one of the lowest people on the social scale.) His name was Gangamāla. When he attended to the King, he would use the razor first, and then he would grasp the hairs with his tweezers. The King liked the first operation, but the second one gave him pain. At the first act he would have given the barber a boon. At the second one he would have cut his head off. One day he told the Queen about it, saying that their court barber was a fool. When she asked what the barber should do, he answered, “Use the tweezers first and the razor afterwards.” She sent for the barber and said, “My good man, when you are trimming the King’s beard, you should take his hairs with your tweezers first and then use the razor afterwards. Then if the King offers you a boon, you must say that you don’t want anything else, but you want to know the meaning of his song. If you do this, I will give you a great deal of money.” He agreed.

On the next day when he was trimming the King’s beard, he used the tweezers first. The King said, “Gangamāla, is this a new method of yours?” “O King,” he answered, “Barbers have got a new way of working.” And he grasped the King’s hair with the tweezer first and used the razor next. The King offered him a boon. “O King, I do not want anything else, but tell me the meaning of your song.”

The King was ashamed to say what his occupation had been in his days of poverty, and he said, “My good man, what is the use of such a boon to you? Choose something else.” But the barber begged for it. The King was afraid to break his word, and so he agreed. As described in the Kummāsapiṇḍa Birth (Jātaka 415), he made proper arrangements. And seated on a jeweled throne, told the whole story of his former act of merit in his last existence in that city. “That explains,” he said, “half the stanza. As for the rest, my comrade became a recluse. From my pride, I am the sole King now, and that explains the second half of my song of ecstasy.”

Hearing him the barber thought, “So the King got this glory for keeping half a fast day. Virtue is the right course. What if I were to become a recluse and work attain my own enlightenment?” He left all of his relatives and worldly goods and obtained the King’s permission to follow the holy life. And going to the Himālaya Mountains, he became a recluse. He realized the three qualities of mundane things (impermanence, suffering, and non-self), gained perfect insight, and became a paccekabuddha. He had a bowl and robes made by supernatural power.

After spending five or six years on the mountain Gangamāla, he wished to see the King of Benares. He passed through the air to the royal park there and sat on the royal stone seat. The park keeper told the King that Gangamāla, now a paccekabuddha, had come through the air and was sitting in the park. The King went at once to salute the paccekabuddha. The Queen Mother also went there with her son. The King entered the park, saluted him, and sat on one side with his retinue. The paccekabuddha spoke to him in a friendly manner, “Brahmadatta” (calling him by the name of the family), “are you diligent, ruling the kingdom righteously, doing charitable and other good works?” The Queen Mother was angry. “This low-caste shampooing son of a barber does not know his place. He calls my kingly high-descended son ‘Brahmadatta’.” And she spoke the seventh stanza:

Penance, indeed, makes men forsake their place,

Their barber’s, potter’s, stations every one.

Through penance Gangamāla gains his praise,

And “Brahmadatta” now he calls my son.

The King admonished his mother, and declaring the qualities of the paccekabuddha, he spoke the eighth stanza:

Lo! How, when his death befall,

Meekness brings a man its fruit!

One who bowed before us all,

Kings and lords must now salute.

And even though the King admonished his mother, the rest of the multitude rose up and said, “It is not proper that such a low-caste person should speak to you by name in that way.” But the King rebuked the multitude, and spoke the last stanza to declare the virtues of the paccekabuddha:

Scorn not Gangamāla so,

Perfect in the Dharma’s ways.

He has crossed the waves of woe,

Free from sorrow now he strays.

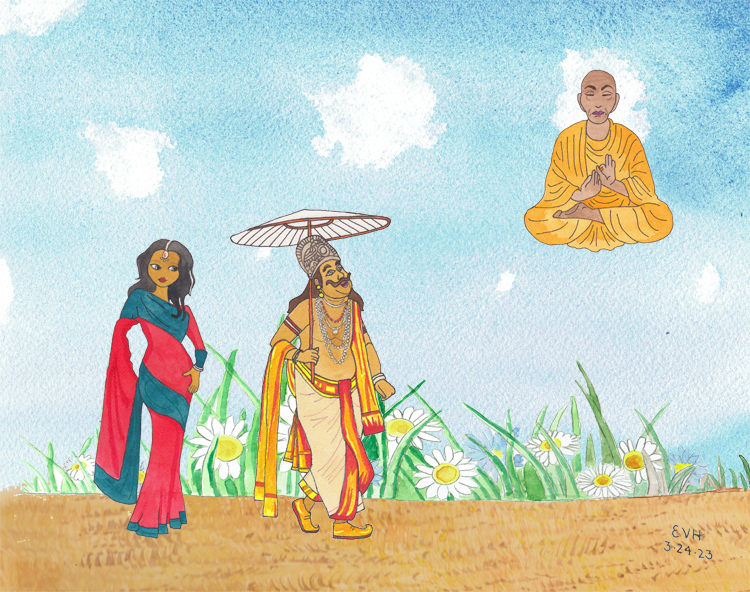

Figure: The King asks for foregiveness

So saying, the King saluted the paccekabuddha and asked him to forgive the Queen Mother. The paccekabuddha did so, and the King’s retinue also gained his forgiveness. The King asked him to promise that he would stay in the neighborhood. But he refused, and standing in the air before the eyes of the whole court, he admonished the King and went away to Gandhamādana.

After the lesson the Master said, “Lay followers, you see how virtue is the proper course.” Then he identified the birth: “At that time the paccekabuddha entered into nirvāna, King Half-penny was Ānanda, the chief Queen was the mother of Rāhula (Yasodhara), and I was King Udaya.”