Jataka 425

Aṭṭhāna Jātaka

The Impossible Conditions

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

The original version of this story and is quite misogynistic. I have changed it to reflect the Buddha’s teaching and his values more closely. It is not—as the original story says—that women are the problem. It is sensual and—in this case—sexual desire. Along with the problem of sense desire is the foolishness of anyone who acts from sensual desire. I think most of us have been there.

But the—perhaps—heroic act in the story is when the merchant’s son renounces worldly life and sensual pleasures to become a recluse. And when the courtesan asks for his forgiveness, he readily grants it. But when she begs him to return to the city, having now realized the fruits of the holy life, he rather poetically gives her impossible conditions upon which he will return. But all’s well that ends well, as the King, too, grants her forgiveness.

“Make the Ganges calm.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about a backsliding monk. The Master asked him, “Is the story true, brother, that you are backsliding?” “Yes, lord.” “What is the cause?” “The power of desire.” “Brother, sensual desire makes you ungrateful, treacherous, and untrustworthy. In the past old wise men could not satisfy a woman, even by giving her a thousand pieces of gold a day. One day, when she did not get the thousand pieces of gold, she had them taken by the neck and cast out. So their sense desire made them foolish. Do not fall into the power of sense desire for such a cause.” And so he told this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, his son, young Brahmadatta, and young Mahādhana, who was the son of a rich merchant of Benares, were comrades and playfellows. They were educated in the same teacher’s house. The Prince became King at his father’s death, and the merchant’s son lived near him.

In Benares there was a certain courtesan. She was beautiful and prosperous. The merchant’s son gave her a thousand pieces of gold every day, and he took pleasure with her constantly. When his father died, he succeeded to the rich merchant’s position. He did not abandon her, still giving her a thousand pieces of gold every day.

He used to visit the King three times a day. One day he went to wait on him in the evening. As he was talking with the King, the sun set, and it became dark. As he left the palace, he thought, “There is no time to go home and then return. I will go straight to the courtesan’s house.” So he dismissed his attendants and entered her house alone.

When she saw him, she asked if he had brought the thousand pieces of gold. “Dear, I was very late today. So I sent my attendants away without going home, and I have come alone. But tomorrow I will give you two thousand pieces of gold.” She thought, “If I service him today, he will come empty-handed on other days, and so my wealth will be lost. I won’t serve him this time.”

So she said, “Sir, I am but a courtesan. I do not give my favors without being paid. You must bring the money.” “Dear, I will bring twice the sum tomorrow.” And so he begged her again and again. But the courtesan gave orders to her maids: “Don't let that man stand there and look at me. Take him by the neck, throw him out, and then shut the door.” They did so.

He thought, “I have spent eighty crores of money on her. Yet on the one day when I come empty-handed, she has me seized by the neck and thrown out. This is wicked, shameless, ungrateful, and treacherous.” And so he reflected on his foolishness until he felt dislike, disgust, and discontentment with a layman’s life. “Why should I lead a layman’s life? I will go this day and become a recluse,” he thought. And so, without even going back to his house or seeing the King again, he left the city and entered the forest. He built a hermitage on the Ganges bank, and there he made his home as a recluse.” He was able to attain the Perfection of Meditation, and there he subsisted on wild roots and fruits.

The King missed his friend and asked about him. The courtesan’s conduct had become known throughout the city. So they told the King of the matter, adding, “O King, they say that your friend did not go home through shame, and he has become a recluse in the forest.” The King summoned the courtesan, and he asked her if the story were true about her treatment of his friend. She confessed. “Wicked, vile woman, go quickly to where my friend is and fetch him. If you fail, you will forfeit your life.”

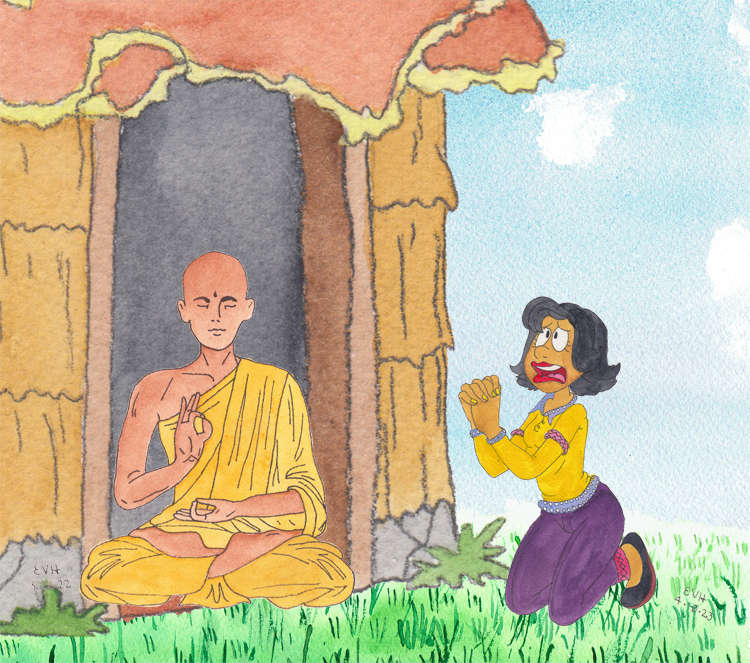

She was afraid at the King’s words. She mounted a chariot and drove out of the city with a great following. She sought for his hut, and—hearing of it by report—she went there. She saluted him and prayed, “Sir, please forgive the evil I did in my blindness and folly. I will never do such a thing again.” “Very well, I forgive you,” he said. “I am not angry with you.” “If you forgive me, please mount the chariot with me. We will drive to the city, and as soon as we enter it, I will give you all the money in my house.”

Figure: “Please forgive the evil I did…”

He replied, “Lady, I cannot go with you now. But when something that cannot happen in this world does happen, then perhaps I will go.” And so he spoke the first stanza:

Make Ganges calm like lotus-tank, cuckoos pearl-white to see,

Make apples bear the palm-trees’ fruit, perchance it then might be.

But she said again, “Please come. I am leaving.” He answered, “I will return.” “When?” “At the appropriate time,” he said, and he spoke the remaining stanzas:

When woven out of tortoise-hair a triple cloth you see,

For winter wear against the cold, perchance it then may be.

When of mosquito’s teeth you build a tower so skillfully,

That will not shake or totter soon, perchance it then may be.

When out of horns of hare you make a ladder skillfully,

Stairs that will climb the height of heaven, perchance it then may be.

When mice to mount those ladder-stairs and eat the moon agree,

And bring down Rāhu from the sky, the thing perchance may be.

When swarms of flies devour strong drink in pitchers full and free,

And house themselves in burning coals, the thing perchance may be.

When asses get them ripe red lips and faces fair to see,

And show their skill in song and dance, the thing perchance may be.

When crows and owls shall meet to talk in converse privily,

And woo each other, lover-like, the thing perchance may be.

When sun-shades, made of tender leaves from off the forest tree,

Are strong against the rushing rain, the thing perchance may be.

When sparrows take Himālaya in all its majesty,

And bear it in their little beaks, the thing perchance may be.

And when a boy can carry light, with all its bravery,

A ship full-rigged for distant seas, the thing perchance may be.

(In Indian mythology, Rāhu is the god that causes eclipses by swallowing the moon or the sun. And, in case the recluse’s meaning is not clear, he is basically saying that he will return when pigs fly, or perhaps when hell freezes over!)

So the Great Being spoke these eleven stanzas to fix impossible (aṭṭhāna) conditions. The courtesan, having truly heard him, won his forgiveness, and she went back to Benares. She told the King what had happened. She begged for her life, and this was granted.

After the lesson, the Master said, “So, monks, sense desire causes ingratitude and treacherous behavior.” Then he taught the Four Noble Truths, after which the backsliding brother was established in the fruition of the First Path (stream-entry). Then the Master identified the birth: “At that time Ānanda was the King, and I was that recluse.”