Jataka 428

Kosambī Jātaka

The Story of Kosambī

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is one of the most famous stories in the whole of the Pāli Canon. It is about the monks at the monastery at Kosambī. They split into two factions over a minor violation of the Vinaya, the monastic code.

Notice how even the Buddha’s own monks will not listen to him. They basically blow him off, which looking back on an event that took place so long ago, seems almost impossible to comprehend. But it shows how powerful foolishness can be when even the Buddha’s own monks will not listen to him. It is a powerful lesson.

Another of the Buddha’s teachings that is emphasized here is that living in solitude is preferable to living among fools. The Jātaka literature is full of stories about paccekabuddhas, non-teaching Buddhas. The Buddha himself thought about whether to teach the Dharma after his awakening. And I can tell you from long experience, that being poorly treated by those who live in ignorance is—as the Buddha characterized it—“wearisome.”

Finally, it is worth noting that in the end, it was the lay people who forced to monks to mend their ways. This is an important theme in Buddhism. If monks or nuns misbehave, it is the role of the lay people to hold them accountable. This is one reason that monks are forced to collect their food every day. It is a system of checks and balances.

“Whene’er the Saṇgha.” The Master told this story while he was at the Ghosita park near Kosambī. It is about certain quarrelsome people at Kosambī. The incident that led to the story is to be found in the section of the Vinaya relating to Kosambī (Mahāvagga 1.10). Here is a short summary of it.

At that time, it is said, two monks lived in the same house. One of them was well-versed in the Vinaya, the other one was well-versed in the sūtras. One day the latter of these monks went to the lavatory. When he left, he left behind some surplus water for rinsing the mouth. Afterwards the monk versed in the Vinaya went in, and seeing the water, he came out and asked his companion if the water had been left there by him. He answered, “Yes, sir.” “What! Do you not know that this is an offense?” “No, I was not aware of it.” “Well, brother, it is.” “Then I will atone for it.” “But if you did it inadvertently and heedlessly, it is not an offense.” So the monk saw no violation in what he had done.

However, the Vinaya scholar said to his pupils, “This sutra scholar, despite committing a violation, is not aware of his offense.” The pupils, when they saw the other monk’s pupils, said, “Even though your master committed an offense, he does not recognize his misdeed.” They went and told their master. He said, “This Vinaya scholar previously stated that it was no offense, and now he says it is. He is a liar.” They went and told the others, “Your master is a liar.” In this way they stirred up a quarrel, one with another. Then the Vinaya scholar, finding an opportunity, initiated the process of excommunication for the brother for refusing to see his offense.

After that, even the lay people who provided requisites for the monks were divided into two factions. The nuns, too, who accept their admonitions, and the tutelary gods, with their friends and intimates and deities from those that rest in space (These include all gods except those in the four highest heavens) to those of the Brahma World, even all those who were unconverted, formed two parties, and the uproar reached to the realm of the Sublime gods.

Then a certain monk went to the Tathāgata. He reported the view of the excommunicating party who said, “The man is excommunicated,” and the view of the followers of the excommunicated one, who said, “He has been illegally excommunicated.” The practice of those who had been forbidden by the excommunicating party, still gathered round in support of him. The Blessed One said, “There is a schism, yea, a schism in the Saṇgha.” He went to them and pointed out the misery involved in excommunication to those that excommunicated, and the misery following upon the denial of the offense to the opposite party. Then he departed.

So when they were holding the Uposatha and similar services in the same place, within the boundary of the monastery, and were quarrelling in the refectory and elsewhere, he laid down the rule that they were to sit down together, one by one from each side alternately. And hearing that they were still quarrelling in the monastery he went there and said, “Enough, brothers. Let us have no quarrelling.”

And one of the excommunicated side, not wishing to annoy the Blessed One, said, “Let the Blessed Lord of the Dharma stay at home. Let the Blessed One live quietly at ease, enjoying the bliss he has already obtained in this life. We shall make ourselves known by this quarrelling, altercation, disputing and contention.”

But the Master said to them, “Once upon a time, brothers, Brahmadatta reigned as the King of Kāsi in Benares. He robbed Dīghati, who was the King of Kosala, of his kingdom. He ordered him put to death. But he lived in disguise, and eventually Prince Dīghāvu spared the life of Brahmadatta. Thereafter they became close friends. And since such must have been the long-suffering and tenderness of these sceptered and sword-bearing kings.”

“In this way, brothers, you ought to make it clear that you, too, having embraced the holy life according to so well-taught a doctrine and discipline, can be forgiving and tender-hearted.” And admonishing them for a third time he said, “Enough, brothers, let there be no quarrelling.” And when he saw that they did not cease at his bidding, he went away, saying, “Verily, these foolish people are like men possessed. They are not easy to persuade.”

On the next day he returned from his alms round. He rested a while in his perfumed chamber. Then he put his room in order, and then taking his bowl and robe he stood poised in the air and delivered these verses in the midst of the assembly:

Whenever the Saṇgha in two is rent,

The common folk to loud-mouthed cries give vent.

Each one believes that he himself is wise,

And views his neighbor with disdainful eyes.

Bewildered souls, puffed up with self-esteem,

With open mouth they foolishly blaspheme.

And as through all the range of speech they stray,

They know not whom as leader to obey.

“This man abused me, that struck me a blow,

A third o’ercame and robbed me long ago.”

All such as harbor feelings of this kind,

To mitigate their wrath are ne’er inclined.

“He did abuse and buffet me of yore

He overcame me and oppressed me sore.”

They who such thoughts refuse to entertain,

Appease their wrath and live at one again.

Not hate, but love alone makes hate to cease.

This is the everlasting law of peace.

Some men the law of self-restraint despise,

But who make up their quarrels, they are wise.

If men all scarred with wounds in deadly strife,

Plunderers and robbers, taking human life,

All those that plunder a whole realm, may be

Friends with their foes, should brothers not agree?

Should you a wise and honest comrade find,

A kindred soul, to dwell with you inclined,

All dangers past, with him you still would stray,

In happy contemplation all the day.

But should you fail to meet with such a friend,

Your life ’twere best in solitude to spend,

Like to some prince that abdicates a throne,

Or elephant that ranges all alone.

For choice adopt the solitary life,

Companionship with fools but leads to strife,

In careless innocence pursue thy way,

Like elephant in forest wild astray.

When the Master had thus spoken, as he failed to reconcile these quarrelsome monks, he went to Bālakaloṇakāragāma (the village of Bālaka, the salt-maker). There he gave a discourse to the venerable Bhagu on the blessings of solitude. Then he repaired to the home of three young men of gentle birth. He spoke to them about the bliss to be found in the sweets of concord. Then he went to the Pārileyyaka forest. After living there for three months, without returning to Kosambī, he went straight to Sāvatthi.

Meanwhile the lay people of Kosambī consulted together and said, “Surely these monks of Kosambī have done us great harm. Worried by them the Blessed One has gone away. We will neither offer salutation nor other marks of respect to them. We will not give alms to them when they visit us. So then they will leave, or they will return to the world, or they will beg forgiveness from the Blessed One.” And they did this. The monks were overwhelmed by this form of punishment. They went to Sāvatthi and begged forgiveness of the Blessed One.

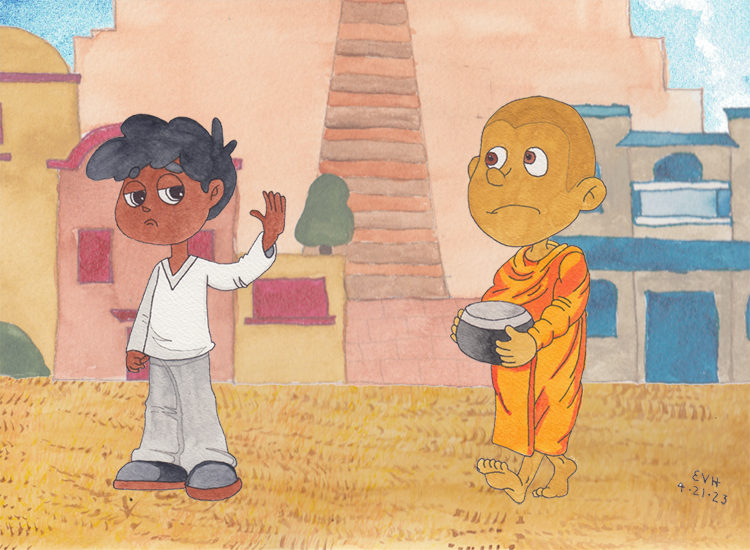

Figure: “Talk to the hand. The alms-giver doesn’t want to listen.”

The Master then identified the birth: “The father was the great King Suddhodana, the mother was Mahāmāyā, and I was Prince Dīghāvu.”

(Suddhodana was the Buddha’s biological father, and Mahāmaya was the Buddha’s biological mother.)