Jataka 469

Mahā Kaṇha Jātaka

Big Blackie

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

According to the Buddhist tradition, at some rare and precious moment in history, a Buddha arises. The Buddha will teach the Dharma, thus “setting in motion the Wheel of the Dharma.” This begins a “Sasana,” a time when the Dharma is known. But eventually practicing the Dharma will become corrupt. It will die out, and knowledge of the Dharma will be lost. This story describes just such an occasion.

“A black, black hound.” The Master told this story when he was staying at Jetavana. It is about living for the benefit of the world.

One day, they say, the monks sat in the Dharma Hall talking together. “Sirs,” one would say, “the Master ever practices friendship towards the multitudes of the people. He has forsaken a comfortable life. He lives just for the good of the world. He has attained supreme wisdom, yet of his own accord he takes bowl and robe and goes on a journey of 18 leagues (about 100 kilometers or 62 miles) or more. For the Five Elders (the five renunciates who accompanied the Buddha when he began his life as an ascetic: Aññakoṇḍañña, Bhaddiya, Vappa, Assaji, Mahānāma), he set the Wheel of the Dharma in motion. On the fifth day of the half-month he recited the Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta (SN 22.59, the second discourse taught by the Buddha. The title means "Not-Self Characteristic Discourse", but is also known as the Pañcavaggiya Sutta, which means the "Group of Five" Discourse) and they all attained liberation. He went to Uruveḷa (a village on the banks of the Nairañjanā River near Bodhgayā. The Buddha spent six years practicing austerities there.), and to the ascetics with matted hair (fire worshippers) he showed miracles and persuaded them to join the Saṇgha. At Gayāsīsa he recited the Discourse on Fire (SN 35.28, the Fire Sermon, which was his third discourse), and a thousand of these ascetics attained liberation. He traveled three miles to meet Mahākassapa. After three discourses he gave him the higher ordination (upasampada). All alone, after the noon-day meal, he traveled 45 leagues (about 250 kilometers or 155 miles), and then established Pukkusa (a youth of very good birth) in the Fruit of the Third Path (non-returner). He traveled 2,ooo leagues (about 11,000 kilometers or 6900 miles) to meet Mahākappina and led him to liberation. Alone, in the afternoon he went on a journey of 30 leagues (about 166 kilometers or 103 miles) where he established that cruel and harsh man Aṅgulimāla in awakening. He also traveled 30 leagues and established Ālavaka in the Fruit of the First Path (stream-entry) and saved the prince. He lived in the Heaven of the Thirty-Three (the Tāvatiṃsa heaven) for three months where he taught full comprehension of the Dharma to 800,000,000 deities. Then he went to Brahma’s world where he destroyed the false doctrine of Baka Brahma and led 10,000 Brahmas to awakening. Every year he goes on pilgrimage in three districts, and to such men as are capable of receiving, he gives the Refuges, the Virtues (Precepts) and the fruits of the different stages (of awakening). He even acts for the good of snakes and garuḷa birds (a mythical (?) type of giant bird) and the like in many ways.” In such words they praised the goodness and worth of the Dasabala’s (Buddha) life for the good of the world. The Master came in and asked what they were discussing as they sat there. They told him. “And no wonder, monks,” he said. “Now I live in perfect wisdom for the world’s good. Even in the past, in the days of passion, I lived for the good of the world.” So saying, he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time, in the days of the Supreme Buddha Kassapa, there reigned a King named Usīnara. It was a long time after the Supreme Buddha Kassapa had declared the Four Noble Truths and liberated multitudes of people from bondage and gone to swell the number of those who dwell in Nirvana. The Sasana (Buddha’s dispensation) had fallen into decay. (Buddhism had disappeared and was no longer practiced) The monastics gained their livelihood in the 21 unlawful ways (practices forbidden to monastics). They associated with the nuns, and sons and daughters were born to them. Monks abandoned the duties of the Saṇgha, and nuns abandoned the duties of sisters, laymen and lay-women abandoned their duties. Brahmins no longer honored the duties of a brahmin. Men for the most part followed the ten paths of evil-doing (killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, slander, harsh speech, gossip, greed, ill-will, and wrong view), and as they died they filled the hosts of all states of suffering.

Then Sakka, observing that no new deities came into being, looked abroad upon the world. He saw how men were born into states of suffering and that the practice of the Buddha had decayed. “What shall I do, now?” he wondered. “Ah, I have it!” he thought. “I will scare and terrify mankind. And when I see they are terrified, I will comfort them. I will declare the Dharma. I will restore the path that has decayed. I will make it last for another thousand years!” With this resolve, he made the god Mātali (his charioteer) into the shape of a huge, pure-bred black hound. He had four tusks as big as a plantain.

He was horrible, with a hideous shape and a fat belly, like a woman ready to give birth to a child. He fastened him to a five-fold chain, and putting a red wreath on him, he led him by a cord. He put on a pair of yellow garments and bound his hair behind his head. He also donned a red wreath. And taking a huge bow fitted with a bowstring the color of coral, he twirled in his fingers a spear tipped with a diamond blade. He assumed the aspect of a forester and descended at a spot one league from the city. “The world is doomed to destruction, is doomed to destruction!” he called out three times with a loud sound. He terrified the people. And when he entered the city, he repeated the cry.

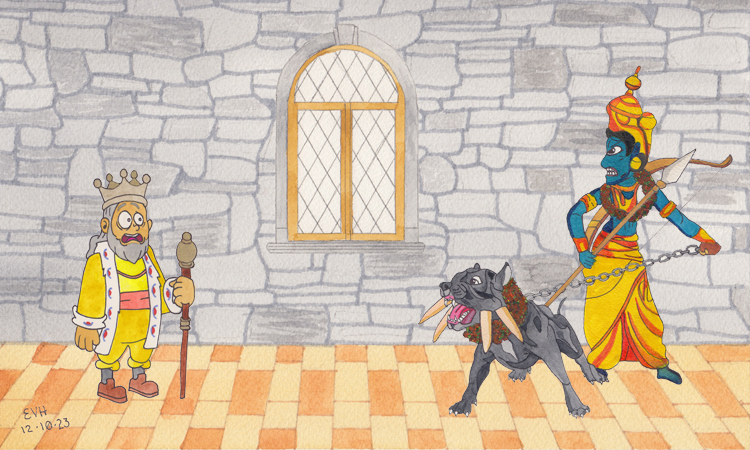

On seeing the hound, the people were frightened and ran into the city. They told the King what had happened. The King speedily caused the city gates to be closed. But Sakka leapt over the wall eighteen cubits (27 feet or 8.23 meters) in height, and with his hound he stood within the city. The people ran away in terror to their houses and locked the doors. Big Blackie gave chase to every man he saw. He scared them, and finally entered into the King’s palace. The people who in fear had taken refuge in the courtyard ran into the palace and shut to the door.

And as for the King, he and the ladies of his household went up on the terrace. Big Blackie raised his forefeet, and putting them in the window, he roared a great roar The sound of his roaring reached from hell to the highest heaven. The whole universe was one great roar. The three great roars that were the loudest ever heard in India are these: the cry of King Puṇṇaka in the Puṇṇaka Birth (Jātaka 545), the cry of the snake-king Sudassana in the Bhūridatta Birth (Jātaka 543), and this roar in the Mahā-Kaṇha Birth, the story of Big Blackie. The people were terrified and horrified, and not one of them could say a word to Sakka.

The King gathered up his courage, and approaching the window, he cried out to Sakka, “Ho, huntsman! Why did your hound roar?” He replied, “The hound is hungry.” “Well,” said the King, “I will order some food to be given him.” So he told them to give him his own food and all the food in his household. The hound ate all of the food with just one gulp, and then he roared again. Again the King put his question. “My hound is still hungry,” was the reply. Then he had all the food of his elephants and horses and so forth brought and given to him. This he also finished off at once. Then the King had all the food in the city given to him. He swallowed this in a similar manner, and then he roared again. The King said, "This is no hound. He is beyond all doubt a goblin. I will ask him from where he has come.” And so, terrified with fear, he asked his question by repeating the first stanza:

“A black, black hound, with five cords bound, with fangs all white of hue,

Majestic, awful—mighty one! what makes he here with you?”

On hearing this, Sakka repeated the second stanza:

“Not to hunt game the Black Hound came, but he shall be of use

To punish men, Usīnara, when I shall let him loose.”

Figure: The The hound terrifies the King.

Then said the King, “What, huntsman! Will the hound devour the flesh of all men or only of your enemies?” “Only my enemies, great King.” “And who are your enemies?” “Those, oh king, who love unrighteousness and walk wickedly.” “Describe them to us,” he said. And the king of the gods described them in the stanzas:

“When the false brothers, bowl in hand, in one robe clad, shall choose

Shaven headed, pursue for wealth, then the Black Hound I will loose.

“When Sisters of the Order shall in single robe be found,

Shaven headed, yet walking in the world, I will let loose the Hound.

“What time ascetics, usurers, protruding the upper lip,

Foul-toothed and filthy-haired shall be—the Black Hound I'll let slip.

“When brahmins, skilled in sacred books and holy rites, shall use

Their skill to sacrifice for gain, the Black Hound shall go loose.

“Who has his parents now grown old, their youth now come to an end,

Would not maintain, although he might ‘gainst him the Hound I’ll send.

“Who to his parents now grown old, their youth now come to an end,

Cries, Fools are you! ‘Gainst such as he the Black Hound I will send.

“When men go after others’ wives, of teacher, or of friend,

Sister of father, uncle’s wife, the Black Hound I will send.

“When shield on shoulder, sword in hand, full-armed as highway men

They take the road to kill and rob, I’ll loose the Black Hound then.

“When widows’ sons, with skin groomed white, in skill all useless found,

Strong-armed, shall quarrel and shall fight, then I will loose the Hound.

“When men with hearts of evil full, false and deceitful men,

Walk in and out the world about, I'll loose the Black Hound then.”

“These,” he said, “are my enemies, oh King!” He feigned as though he would let the hound leap forth and devour all those who did the deeds of enemies. But as the multitude was struck with terror, he held restrained the hound by the leash.

Then casting off the disguise of a hunter, by his power he rose and poised himself in the air. He appeared all blazing. He said, “Oh great King, I am Sakka king of the gods! Seeing that the world was about to be destroyed, I came here. Now, indeed, men as they die are filling the states of suffering because their deeds are evil, and heaven has become empty. From here forward I will know how to deal with the wicked, but do you be vigilant.” Then, having in four stanzas well worth remembering, he declared the Dharma. And established the people in the virtues of generosity, he strengthened the waning power of the Sasana so that it lasted for yet another thousand years, and then with Mātali, he returned to his own domain.

When the Master ended this discourse, he added, “Thus, brothers, in former times as now I have lived for the good of the world.” And then he identified the birth: “At that time Ānanda was Mātali, and I was Sakka.”