Jataka 502

Haṃsa Jātaka

The Goose

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

We have seen—and will see—this story in several forms. They are all about self-sacrifice, specifically that of the Buddha’s attendant Ānanda and his dedication to the Buddha.

“There go the birds.” The Master told this story while he was living at the Bamboo Grove (Veluvana). It is about Elder Ānanda’s renunciation of worldly life. The monks were discussing the Elder’s good qualities in the Dharma Hall when the Master came in and asked them what they were discussing. He said, “This is not the first time, brothers, that Ānanda has renounced his worldly life for my sake. He has done this before.” And then he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time, a King named Bahuputtaka— or the Father of Many Sons—reigned in Benares. His Queen Consort was Khemā. At that time the Great Being lived on Mount Cittakūṭa. He was the chief of 90,000 wild geese, having come into life as a golden goose. And at that time, as already recounted, the Queen had a dream. She told the King she had a desire to hear a Golden Goose give a teaching on the Dharma. When the King asked if there were such creatures as golden geese, he was told yes, and that they were on Mount Cittakūṭa.

He built a lake that he called Khemā. He had planted all manner of food grains there. And every day in the four quarters he proclaimed immunity, and then he sent out a hunter to catch geese. How this man was sent, how he watched the birds, how news was given to the King when the golden geese arrived, in the manner in which the snare was set and the Great Being was caught in the snare, how Sumukha—chief captain of the geese—did not see him in the three groups of fleeing geese, and how she returned, all this will be set forth in the Mahāhaṁsa Birth (Jātaka 534, where the king of the geese is named Dhataraṭṭha).

Now as then the Great Being was caught in the noose and stick, and even as he hung in the noose at the end of the stick, he stretched his neck looking to see the direction in which the geese had gone. And seeing Sumukha, he thought, “When he comes, I will test him.” So when he arrived, the Great Being repeated three stanzas:

“There go the birds, the ruddy geese, all overcome with fear,

O golden-yellow Sumukha, depart! What want you here?

“My kith and kin deserted me, away they all have flown,

Without a thought they fly away, why are you left alone?

“Fly, noble bird! with prisoners no fellowship can be,

Sumukha, fly! Or lose the chance while you may yet be free.”

To which Sumukha replied, sitting on the mud:

“No, I’ll not leave you, Royal Goose, when trouble draws a sigh,

But stay I will, and by your side will either live or die.”

Thus Sumukha, with a lion’s note, and Dhataraṭṭha answered with this stanza:

“A noble heart, brave words are these, Sumukha, which you say,

‘Twas but to put you to the test I begged you fly away.”

As they were talking together, the huntsman arrived, staff in hand, at the top of his speed. Sumukha encouraged Dhataraṭṭha and flew to meet the man, respectfully declaring the virtues of the royal bird. Immediately the hunter’s heart was softened. Sumukha perceived this and went returned, encouraging the king of the geese. The hunter approached the king of the geese and recited the sixth stanza:

“They foot it by unfooted ways, birds flying in the sky,

And did you not, O noble Goose, see the snare close by?”

The Great Being said:

“When life is coming to an end, and death’s hour is your plight,

Though you may come close to it no trap or snare’s in sight."

The hunter, pleased with the bird’s remark, then addressed three stanzas to Sumukha.

“There go the birds, the ruddy geese, all overcome with fear,

And you, O golden-yellow fowl, are still left waiting here.

“They ate and drank, the ruddy geese, uncaring, they have flown,

Away they scurry through the air, and you are left alone.

“What is this fowl, that when the rest deserting him have flown,

Though free, you join the prisoner—why are you left alone?”

Sumukha replied:

“He is my comrade, friend, and king, dear as my life is he,

Forsake him—no, I never will, until death calls for me.”

On hearing this the hunter was pleased. He thought to himself, “If I should harm virtuous creatures like these, the earth would rip open and swallow me up. What do I care about the King’s reward? I will set them free." And he repeated a stanza:

“Now seeing that for friendship’s sake you are prepared to die,

I set your king and comrade free, to follow where you fly.”

This said, he drew down Dhataraṭṭha from the stick. He released the noose and took him to the bank, where he gently washed the blood from him and set the dislocated muscles and tendons. And motivated by his kindness and by the might of the Great Being's Perfections (the Ten Perfections: generosity, virtue, renunciation, wisdom, energy, patience, honesty, determination, loving-kindness, and equanimity), in an instant his foot became whole again. There was not a mark showing where he had been injured. Sumukha beheld the Great Being with joy. He gave thanks in these words:

“With all your kindred and your friends, O hunter, happy be,

As I am happy to behold the king of birds set free.”

When the hunter heard this, he said, “Now you may depart, friend.” Then the Great Being said to him, “Did you capture me for your own purposes, my good sir, or at the bidding of another?” He told him the facts. The other wondered whether it would be better to return to Cittakūṭa or to go to the town. “If I go to the town,” he thought, “the hunter will be rewarded, the Queen’s craving will be appeased, Sumukha’s friendship will be made known, and then by virtue of my wisdom I shall receive the Lake Khemā as a free gift. It is better, therefore, to go to the city.” This determined, he said, “Huntsman, take us on your carrying pole to the King, and he shall set me free if it is his will.” “My lord, kings are hard. You should go your own way.” “What! I have softened a hunter like you, and I shall not find favor with a King? Leave that to me. Your part, friend, is to take us to him.” The man did so.

When the King saw the geese, he was delighted. He placed both the geese on a golden perch. He gave them honey and fried grain to eat and sweetened water to drink. And holding his hands out in humility, he begged them to teach the Dharma. The king of the geese saw how eager he was to hear. He first addressed him in pleasant words. These are the stanzas of the conversation between the King the goose:

“Now has his honor health and wealth, and is the kingdom full

Of welfare and prosperity, and does he justly rule?”

“O here is health and wealth, O goose, and here’s a kingdom full

Of welfare and prosperity, with just and righteous rule.”

“Is there no blemish seen amid your court, and are your foes

Far off, and like the shadow on the south, which never grows?”

“There is no blemish seen amid my courtiers, and my foes

Far off are like the shadow on the south, which never grows.”

“And is your Queen of equal birth, obedient, sweet of speech,

Fruitful, fair, famous, waiting on your wishes, doing each?”

“O yes, my Queen’s of equal birth, obedient, sweet of speech,

Fruitful, fair, famous, waiting on my wishes, doing each.”

“O fostering ruler! Have you sons a many, nobly bred,

Quick witted, easy men to please whatever thing be sped?”

“O Dhataraṭṭha! sons I have of fame, five score and one,

Tell them their duty, they'll not leave your good advice undone.”

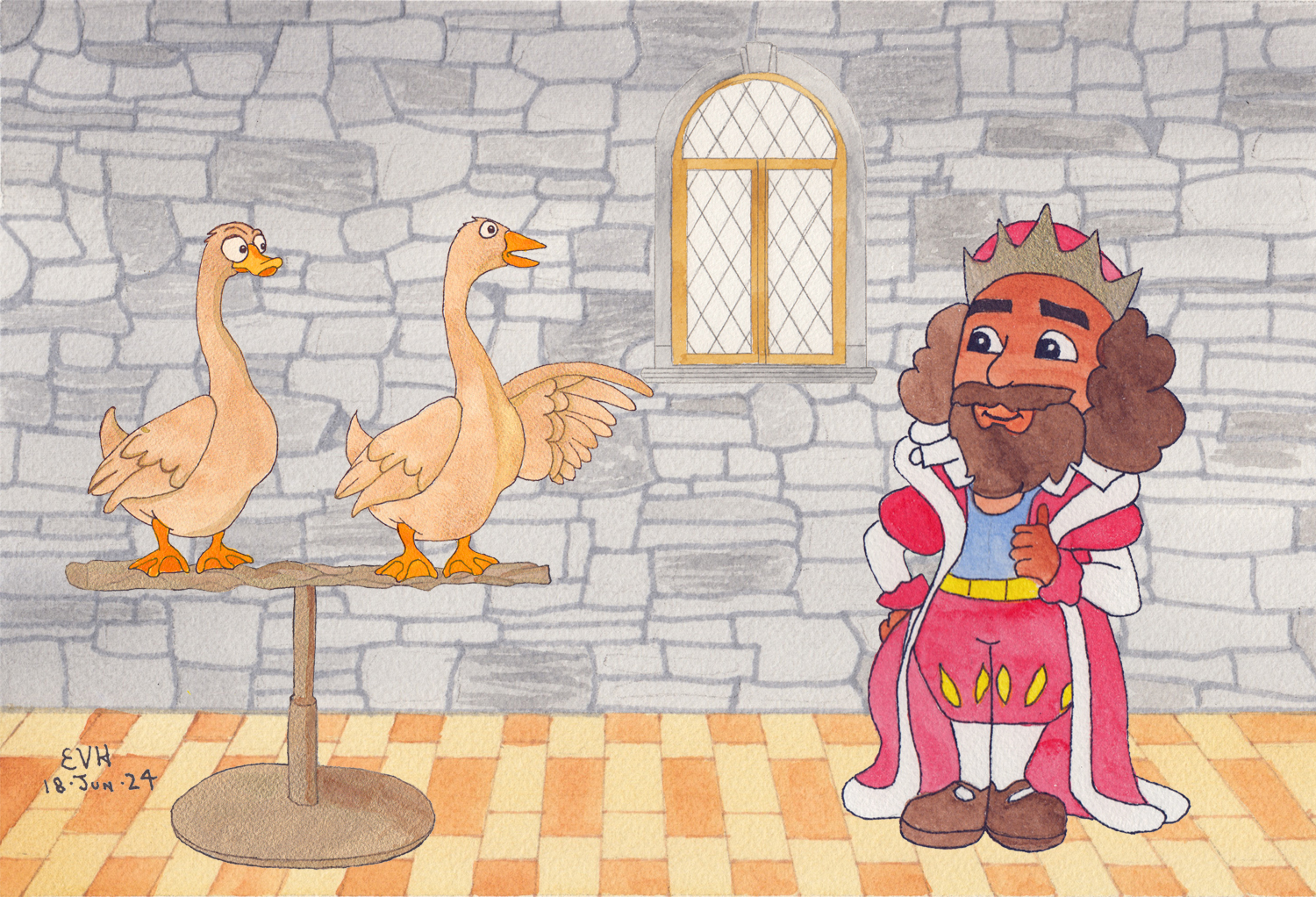

Figure: King goose teaches the King.

On hearing this, the Great Being gave them an admonition in five stanzas:

“He that puts off until too late the effort to do good,

Though nobly bred, with virtue dowered, yet sinks beneath the flood.

“His knowledge fades, great loss is his, as one moonblind at night,

Sees all things swollen twice their size with his imperfect sight.

“Who sees the truth in falsity gains no wisdom at all,

As on a rugged mountain path the deer will often fall.

“If any strong courageous man loves virtue, follows right,

Though but a low-born fool, he burns like bonfires in the night.

“By using this similitude all wisdom’s truths explain,

Cherish your sons till wise they grow, like seedlings in the rain.”

In this way the Great Being taught the King the whole night. The Queen’s craving was satisfied. By sunrise he established him in the virtues of kings and exhorted him to be vigilant. Then with Sumukha, he flew out of the northern window and went back to Cittakūṭa.

After this discourse, the Master said, “Thus, brothers, this man offered his life for me before.” Then he identified the birth: “At that time Channa was the huntsman, Sāriputta was the King, a sister was Queen Khemā, the Sākiya tribe was the flock of geese, Ānanda was Sumukha, and I was the Goose King.”