Jataka 509

Hatthipāla Jātaka

The Story of Hatthipāla

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a charming story and a bit of a Buddhist fantasy. In it, one by one, people in the city of Benares renounce worldly affairs to seek the holy life. The god Sakka sees what they are doing, and has the celestial architect build an enormous refuge for them in the Himalayas. Ah! To live in this story!

Also, note that the name “Hatthipāla” literally means “elephant protector.” The word “hatthi” means “elephant,” and “pāla” means “a guard, keeper, and protector.”

“At last we see.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about the renunciation. Then with these words, he said, “It is not the first time, brothers, that the Tathāgata made the renunciation. It was so before.” Then the Master told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time there reigned a King named Esukārī in Benares. His chaplain had been his favorite companion from the days of his youth. They were both childless. As the two were sitting together one day in a friendly manner, they thought, “We have great glory, but neither one of us has a son or a daughter. What can we do about this?” Then the King said to the chaplain, “Friend, if a son is born in your house, he shall be the lord of my kingdom. But if I have a son, he shall be the master of your wealth.” The two made an agreement on these terms.

One day, as the chaplain approached his revenue village, he entered by the southern gate. Outside the gate he saw a wretched woman who had seven sons. All of them were hale and hearty. One held a pot and plate for cooking. One had a mat and bedding. One went on before and one followed behind. One held her finger. One sat on her hip, and one sat on her shoulder. “Where,” asked the chaplain, “is the father of these lads?” “Sir,” she replied, “the lads have no father at all for certain.” “Why then,” he said,” how did you get seven fine sons like that?” (Some women in India were said to be married to certain trees. This woman may belong to that class.) Disregarding the rest of the jungle, she pointed out a banyan tree that stood by the city gate. She said, “I offered a prayer, sir, to the deity who inhabits this tree. She answered me by giving these lads.” “You may go, then,” the chaplain said. Descending from his chariot, he went up to the tree. And taking hold of a branch, he shook it, saying, “O divinity, what has the King failed to give you? Year by year he offers you in tribute a thousand gold coins, and yet you do not give him a son. What has this beggar woman done for you that you give her seven children? You will grant the King a son within seven days, or I will have you cut down by the roots and chopped up into pieces.” So reprimanding the deity of the banyan tree, he went away.

Day after day for six days he did the same. And on the sixth day, grasping a branch he said,” Only one night is left, tree god. If you do not grant a son to my King, down you come!”

The deity of the tree reflected until she knew exactly what the matter was. “That brahmin,” she thought, “will destroy my home if he does not get a son. Well, how can I get him a son?” Then she went before the four great kings (Four Lords of the Earth, North, South, East, and West) and told them. “Well,” they said, “we cannot give the man a son.” Next she went to the 28 warlords of the goblins, and they all said the same thing. She went to Sakka, king of the gods, and told him. He pondered to himself, “Shall the King get sons worthy of him, or not?” Then he looked about and saw four meritorious sons of the gods. These men, it is said, had been weavers in Benares in a former existence. They divided their earnings from that trade into five shares. They each kept one of the four shares as their own. But the fifth share they gave away in common. Because of their generosity, they were reborn in the Heaven of the Thirty-three (the Tāvatiṃsa heaven, a very auspicious rebirth). Then they were born into the Yāma world. (Yāma is the third of the six heavenly worlds of the desire realm in Buddhist cosmology.) Then in due succession they were reborn up and down through the six celestial worlds, and they enjoyed much glory.

Just then it was time for them to go from the Heaven of the Thirty-three to the Yāma Heaven. Sakka went to see them. He summoned them and said, “Holy sirs, you must go to the world of men to be conceived in the womb of King Esukārī’s chief consort.” “Good, my lord,” they said to him. “We will go. But we do not want anything to do with a royal house. We will be born in the chaplain’s family, and while yet we are still young, we will renounce the world.” Sakka approved them for their promise and returned. He told all of this to the deity that lived in the tree. Very pleased, the tree god took leave of Sakka and went back to her dwelling place.

On the next day the chaplain arrived. He brought with him strong men whom he had gathered. Each had a razor-sharp axe or the like. The chaplain approached the tree, and seizing a branch, he cried out, “What ho, god of the tree! This is now the seventh day since I begged a favor of you. The time of your destruction has come!” Using her great power, the tree deity split open the tree trunk and came forth. And in a sweet voice she addressed him, “One son, brahmin? Pooh! I will give you four.” He said, “I want no sons. Give one to my King.” “No,” she said, “I will give them only to you.” “Then give two to the King and two to me.” “No, the King will have none. You will have all four. They will only be given to you, for they will not live in a worldly household. In the days of their youth, they will renounce the world.” “Just give me the sons, and I will see to it they do not renounce the world,” he said. And so the deity granted his prayer for children and returned to her home. And from then on, that deity was held in high honor.

Now the eldest god came down and was conceived by the brahmin’s wife. On his name day they called him Hatthipāla, the Elephant Driver. To prevent him from renouncing the world, they put him in the care of some elephant keepers, among whom he grew up. When he was old enough to walk, the second son was born of the same woman. At his birth they named him Assapāla, or Groom, and he grew up among those who kept horses. When the third son was born, he was named Gopāla, the Cowherd. He grew up among the cattle breeders. Ajapāla, or Goatherd, was the name given to the fourth son. When he was born, he grew up among the goat herds. When they grew older, they were young of auspicious significance.

Now out of fear of their renouncing the world, all the ascetics who had done so were banished from the kingdom. In the whole realm of Kāsi not one was left. The boys were rough. Wherever they went, they plundered any gifts of ceremony that were sent here or there.

When Hatthipāla was sixteen years old, the King and the chaplain—seeing his bodily perfection—thought, “The lads have grown big. When the umbrella of royalty is lifted, what shall we do with them? As soon as the ceremony of sprinkling is done upon them, they will grow very masterful. Ascetics will come. They will see them and will become ascetics also. Once they have done this, the whole country will be in confusion. First let us test them, and afterwards we will have the ceremonial sprinkling.” (The “ceremonial sprinkling” is a religious ceremony performed at auspicious times. In this case it would have made Hatthipāla the King.) So they both dressed themselves up like ascetics. They went about seeking alms until they came to the door of the house where Hatthipāla lived. The lad was pleased and delighted to see them. He greeted them with respect, and recited three stanzas:

“At last we see a brahmin like a god, with top-knot great,

With teeth uncleansed, and foul with dust and burdened with a weight.

“At last we see a sage, who takes delight in righteousness,

With robes of bark to cover him and with the yellow dress.

“Accept a seat, and for your feet fresh water, it is right

To offer gifts of food to guests—accept, as we invite.”

In this way he addressed them one after the other. Then the chaplain said to him, “Hatthipāla my son, you say this because you do not know us. You think we are sages from the Himalayas, but we are not, my son. This is King Esukārī, and I am your father the chaplain.” “Then,” said the lad, “why are you dressed like sages?” “To try you,” he said. “Why try me?” he asked. “Because, if you see us without renouncing the world, we are ready to perform the ceremony of sprinkling and make you King.” “Oh, my father,” he said, “I want no royalty. I will renounce the world.” Then his father replied, “Son Hatthipāla, this is not a time for renouncing the world,” and he explained his intent in the fourth stanza:

“First learn the Vedas, get you wealth and wife

And sons, enjoy the pleasant things of life,

Smell, taste, and every sense, sweet is the wood

To live in then, and then the sage is good.”

Hatthipāla replied with a stanza:

“Truth comes not by the Vedas or by gold,

Or getting sons will keep from getting old.

From sense desire is release, wise men know,

In the next birth we reap as now we sow.”

In answer to the young man, the King now recited a stanza:

“Most true the words that from your lips do go,

In the next birth we reap as now we sow.

Your parents now are old, but may they see

A hundred years of health in store for thee.”

“What do you mean, my lord?” asked the Prince, and he repeated two stanzas:

“He who in death, O King, a friend can find,

And with old age a covenant has signed.

For him who will not die be this your prayer,

A hundred years of life to be his share.

“As one who on a river ferries o’er

A boat, and journeys to the other shore,

So mortals do inevitably tend

To sickness and old age, and death’s the end.”

In this way he showed how transient the conditions of mortal life are, adding this advice, “As you stand there, O great King, and as I speak with you, even now sickness, old age, and death are drawing nearer to me. Then be vigilant!” So saluting the King and his father, he took his attendants with him and forsook the kingdom of Benares. He left with the intention to embrace the holy life. And a great company of people went with the young man Hatthipāla. “For,” they said, “this holy life must be a noble thing.” The gathering extended a league long. With this company he proceeded until he came to the bank of the Ganges. There he attained deep meditative absorption by gazing at the water of the Ganges. “There will be a great gathering here,” he thought. “My three younger brothers will come, my parents, King, Queen, and all of them. They will come with their attendants and embrace the holy life. Benares will be empty. And until they come, I will remain here.” So he sat there, exhorting the assembled crowd.

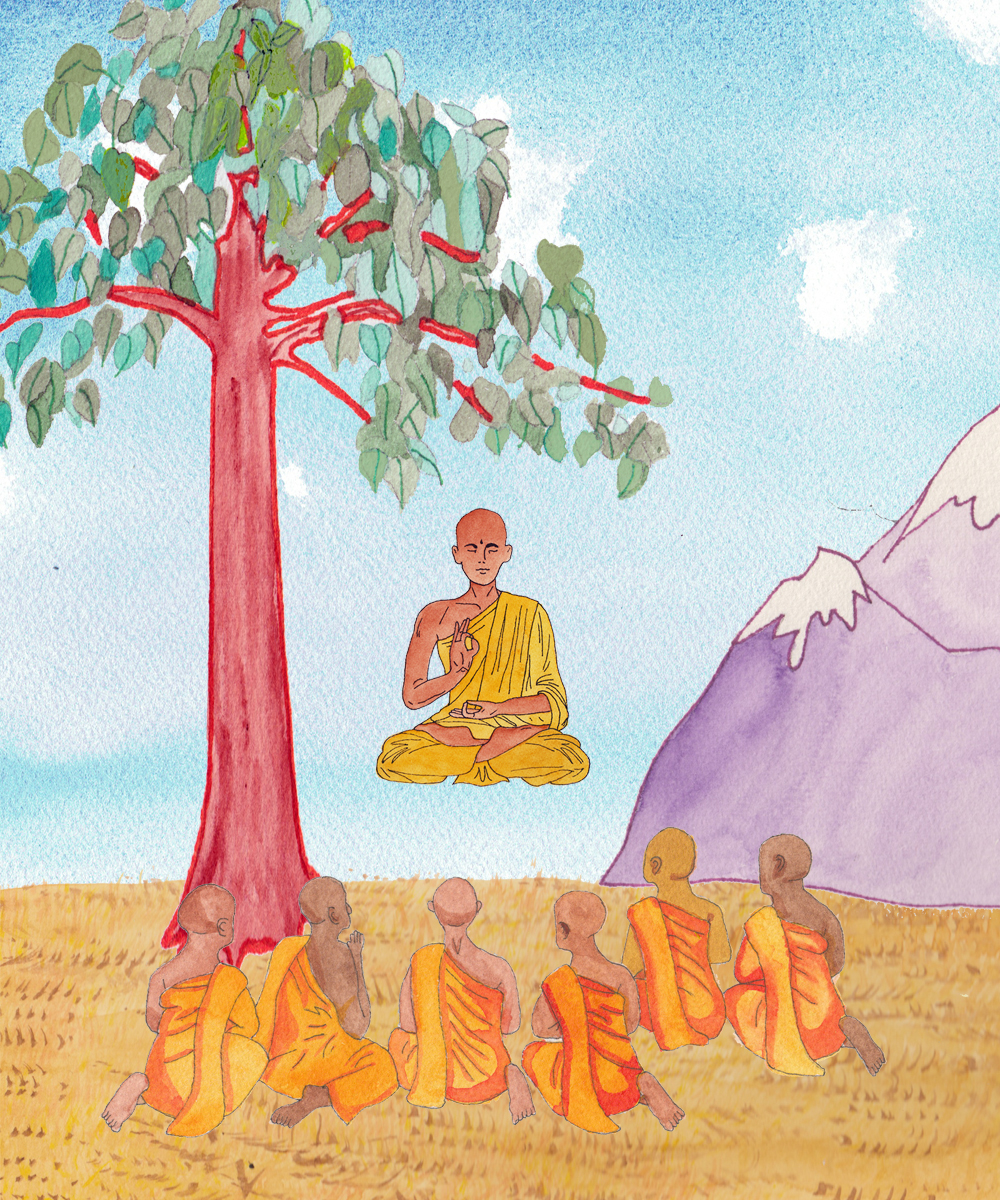

Figure: Hatthipāla declares the Dharma.

On the next day the King and his chaplain thought, “And so Prince Hatthipāla has really renounced his claim on the kingdom. He is sitting on the Ganges bank where he went to follow the holy life. And he took a great many with him. But let us try Assapāla. We will sprinkle him to be King.” So as before, dressed as ascetics they went to his door. He was pleased when he saw them. He went up to them and repeated the lines, “At last,” and so forth. He did as his older brother had done. The others did as before. They told him the reason they came. He said, “Why is the White Umbrella offered first to me seeing that I have a brother, Prince Hatthipāla?” They answered, “Your brother has gone away, my son, to embrace the holy life. He would have nothing to do with royalty.” “Where is he now?” asked the lad. “Sitting on the bank of the Ganges.” “Dear ones,” he said, “I do not care for anything that my brother has spurned. Fools and they who are devoid of wisdom cannot renounce these defilements, but I will renounce them.” Then he declared the Dharma to his father and the King in two stanzas that he recited:

“Pleasures of sense are but morass and mire,

The heart’s delight brings death and troubles sore.

Who sink in these morasses come no nearer

In foolish madness to the farther shore.

“Here’s one who once inflicted grief and pain,

Now he is caught, and no release is found.

That he may never do such things again

I’ll build impenetrable walls around.”

“There you stand, and even as I speak with you, sickness, old age, and death are approaching nearer.” With this admonition and followed by a company of people a league long, he went to his brother Prince Hatthipāla. Hatthipāla declared the Dharma to him. Poised in the air, he said, “Brother, there will be a great gathering in this place. Let us both stay here together.” And so he agreed.

On the next day the King and chaplain went in the same manner to the house of Prince Gopāla. He greeted them with the same joy. They explained the reason for their coming. He—like Assapāla—refused their offer. “For a long time,” he said, “I have wished to embrace the holy life. Like a cow astray in the forest, I have been wandering about in search of this life. I have seen the path by which my brothers have gone, like the track of a lost cow, and by that same path I will go.” Then he repeated a stanza:

“Like one who seeks a cow that lost her way,

Who all perplexed about the wood does stray.

So is my welfare lost, then why hang back,

King Esukārī, to pursue the track?”

“But,” they replied, “come with us for a day, son Gopālaka, for two or three days come with us. Make us happy, and then you can renounce the world.” He said, “O great King! Never put off until tomorrow what ought to be done today. If you want luck, grab today by the mane.” Then he recited another stanza:

“Tomorrow! Cries the fool. Next day! He cries.

No safety in the future! Say the wise.

The good within his reach he’ll ne’er despise.”

Thus spoke Gopāla, declaring the Dharma in the two stanzas. Then he added, “There you stand, and even as I talk with you, you are approaching sickness, old age, and death.” Then followed by a company of people a league in length, he made his way to his two brothers. And Hatthipāla—poised in the air—declared the Dharma to him also.

On the next day, in the same manner the King and chaplain visited the house of Prince Ajapāla. He greeted them with joy as the others had done. They told him the cause of their coming and proposed to upraise the umbrella of royal authority over him. The Prince said, “Where are my brothers?” They answered, “Your brothers will have nothing to do with the kingdom. They have renounced the White Umbrella of royal authority, and with a company that covers three leagues they are sitting on the bank of the Ganges.” “I will not put on my head that which my brothers have spurned and live in that way. I, too, will undertake the holy life.” They said, “My son, you are very young. Your welfare is our responsibility. Grow older, and then you can embrace the holy life.” But the lad said, “What is this you say? Surely death comes in youth as in age! No one knows whether he will die young or die old. I do not know the time of my death, so I will renounce the world altogether now.” He then recited two stanzas:

“Oft have I seen a maiden young and fair,

Bright-eyed, intoxicate with life, her share

Of joy untasted yet, in youth’s first spring.

Death came and carried off the tender thing.

“So noble, handsome lads, well-made and young,

Round whose dark chins the beard in clusters clung—

I leave the world and all its lusts, to be

A hermit, you go home and pardon me.”

Then he went on. “There you stand, and even as I talk with you sickness, old age, and death are approaching me.” He saluted them both, and at the head of a league-long company, he repaired to the bank of the Ganges. Hatthipāla—poised in the air—declared the Dharma to him also and sat down to wait for the great gathering that he expected.

On the next day the chaplain began to meditate as he sat on his couch. “My sons,” he thought, “have embraced the holy life, and now I am alone, the withered stump of a man. I will follow the holy life as well.” Then he addressed this stanza to his wife:

“That which has branching boughs a tree they call,

Disbranched, it is a trunk, no tree at all.

So is a childless man, my high-born wife,

‘Tis time for me to embrace the holy life.”

This said, he summoned the brahmins before him. Sixty thousand of them came. Then he asked them what they wanted to do. “You are our teacher,” they said. “Well,” he said, “I will seek out my son and embrace the holy life.” They answered, “Hell is not hot for you alone. we will do likewise.” He handed over his treasure of eighty crores (a crore is 10 million rupees) to his wife, and at the head of a league-long train of brahmins, he departed to the place where his sons were. And to this company—as before—Hatthipāla declared the Dharma as he was poised high in the air.

On the next day the wife thought to herself, “My four sons have refused the White Umbrella to follow the holy life. My husband has left his fortune of eighty thousand crores and his position of royal chaplain to boot, and he has gone to join his sons. What am I to do all by myself? By the path my son has taken, I will go as well.” And quoting an ancient saying, she recited this stanza of inspiration:

“The rain-months past, the geese break net and snare,

With a free flight like herons through the air,

So by the path of husband and of son

I’ll seek for knowledge as they all have done.”

“Since I know this,” she said to herself, “why should I not renounce the world?” With this intention she summoned the brahmin women. She said to them, “What do you intend to do with yourselves?” They asked, “What will you do?” “As for me, I shall renounce the world.” “Then we will do the same.” So leaving all her splendor, she followed after her sons, taking with her a league-long company of women. To this company Hatthipāla also declared the Dharma sitting poised in the air.

On the next day the King asked, “Where is my chaplain?” “My lord,” they replied, “the chaplain and his wife have left all their wealth behind and have gone after their sons with a company that covers several leagues.” The King said, “Masterless money comes to me,” and he sent courtiers to fetch it from the chaplain’s house. The Chief Queen now wanted to know what the King was doing. “He is fetching the treasure,” she was told, “from the chaplain’s house.” “And where is the chaplain?” she asked. “He went to lead the holy life, wife and all.” “Why,” she thought, “here is the King fetching the dung and the spittle dropped by this brahmin and his wife and his four sons into his own house! Infatuate fool! I will teach him by a parable.”

She got some dog’s flesh and piled it in the palace courtyard. Then she set a snare round it, leaving the way open straight overhead. The vultures saw it from afar and swooped down. The wise among them noticed that a snare had been set around it. And feeling they were too heavy to fly up straight, they disgorged what they had eaten, and without being caught in the snare, they rose up and flew away. But others who were blind with folly devoured the meat, and being heavy they could not get fly away but were caught in the snare. They brought one of the vultures to the Queen, and she took it to the King. “See, O King!” she said, “there is a sight for us in the courtyard.” Then opening a window, she said “Look at those vultures, your majesty!” Then she repeated two stanzas:

“The birds that ate and vomited in the air are flying free,

But those That ate and kept it down are captured now by me.

“A brahmin vomits out his lusts and will you eat the same

A man who gorges sense desire, deserves the deepest blame.”

At these words the King repented. The three states of existence (sensual, bodily, and formless, referring to the three correspondent worlds) seemed like blazing fires. He said, “This very day I must leave my kingdom and embrace the holy life.” Full of remorse, he praised his Queen in a stanza:

“Like as a strong man lends a helping hand

To weaker, sunk in mire or in quicksand,

So, Queen Pañcātī, you have saved me here,

With verses sung so sweetly in my ear.”

No sooner had he said this, then he sent for his courtiers, eager to undertake the holy life. He said to them, “And what will you do?” They answered, “What will you?” He said, “I will seek Hatthipāla and embrace the holy life.” “Then,” they said, “we, my lord, will do the same.” The King renounced his sovereignty over Benares, that great city, twelve leagues in extent and he said, “Let the Queen raise the White Umbrella.” Then surrounded by his courtiers, at the head of a column three leagues in length, he went to the presence of the young man. To this body Hatthipāla also declared the Dharma, sitting high in the air.

The Master repeated a stanza that told how the King renounced this world.

“Thus Esukārī, mighty King, the lord of many lands,

From King turned hermit, like an elephant that bursts his bands.”

On the next day the people who were left in the city gathered before the palace door. They sent word to the Queen. They entered, and saluting the Queen, they stood on one side, repeating a stanza:

“It is the pleasure of our noble King

To be a hermit, leaving everything.

So in the King’s place now we pray you stand,

Cherish the realm, protected by our hand.”

She listened to what the crowd said, and then repeated the remaining stanzas:

“It is the pleasure of the noble King

To be a hermit, leaving everything.

Knowing that I will walk the world alone,

Renouncing lusts and pleasures every one.

“It is the pleasure of the noble King

To be a hermit, leaving everything.

Knowing that I will walk the world alone,

Where’er they be, renouncing lusts each one.

“Time passes on, night after night goes by,

Youth’s beauties one by one must fade and die.

Knowing that I will walk the world alone,

Renouncing lusts and pleasures every one.

“Time passes on, night after night goes by,

Youth’s beauties one by one must fade and die.

Knowing that I will walk the world alone,

Where’er they be, renouncing lusts each one.

“Time passes on, night after night goes by,

Youth’s beauties one by one must fade and die.

Knowing that I will walk the world alone,

Each bond thrown off, nor passion’s power I own.”

In these stanzas she declared the Dharma to the great crowd. Then summoning the courtier’s wives, she said to them, “And what will you do?” “Madam,” they said, “what will you?” “I will embrace the holy life.” ”Then so will we.” So the Queen opened the doors of all the storehouses of gold in the palace, and she had engraved on a golden plate, “In such a place is a great hidden treasure. Anyone who chooses may have it.” She fastened this gold plate to a pillar on the great royal dais and sent the drum beating the proclamation about the city. Then leaving all her magnificence, she departed from the city.

The whole city was in turmoil. They cried, “Our King and Queen have left the city to follow the holy life. What are we to do now?” Then the people all left their houses and all that was in them. They went out, taking their sons by the hand. All the shops stood open, but no one so much as turned to look at them. The whole city was empty.

With an attendant train of three leagues in length, the Queen went to the same place as the others. To this company Hatthipāla also declared the Dharma, poised in the air above them. And then with the whole train a dozen leagues long, he set out for the Himalaya Mountains.

All Kāsi was in an uproar, crying how young Hatthipāla had emptied the city of Benares, twelve leagues in extent, and how with a huge company he went off to the Himalaya Mountains to embrace the holy life. “Surely then,” they said, “we should do it as well!” In the end this company grew so that it covered thirty leagues. And with this great company, he went to the Himalaya Mountains.

In his meditation Sakka perceived what was happening. “Prince Hatthipāla,” he thought, “has made the renunciation. There will be a great gathering of people, and they must have a place in which to live.” He gave orders to Vissakamma (the celestial architect). “Go, make a hermitage that is 36 leagues long and 15 leagues wide, and gather in it all that is necessary for the holy life.” He obeyed and made a hermitage of the required size on the bank of the Ganges bank in a pleasant spot. He prepared mattresses in the leaf-huts with twigs or leaves. He prepared all things necessary for the holy life. Each hut had a paved path (for walking meditation). There were separate places for night and day living. Everything was neatly worked over with whitewash. There were benches for rest. Here and there were flowering trees all laden with fragrant blooms of many colors. At the end of each walking path there was a well for drawing water and beside it was a fruit tree. Each tree bore all manner of fruits. This was all done by divine power. When Vissakamma had finished the hermitage and provided the leaf huts with all the necessary things, he inscribed on a wall in letters of vermilion, “Whoever will embrace the holy life is welcome to these necessary things.” Then by his supernatural power he banished from that place all hideous sounds, all hateful beasts and birds, all unhuman beings, and he went back to his own realm.

Hatthipāla came upon this hermitage, Sakka’s gift, by a footpath, and he saw the inscription. He thought, “Sakka must have perceived that I have made the Great Renunciation.” He opened a door and entered a hut. And taking those things that mark the ascetic, he went out again along the walking path, walking up and down a few times. Then he admitted the rest of the company to the holy life and went to inspect the hermitage. In the middle he established a place for women with young boys. The place next he set aside for the old women. Next was a place for childless women. The other huts he allotted to men.

Then a certain King, hearing that there was no King in Benares, went to see it. He found the city adorned and decorated. Entering the royal palace, he saw the treasure lying in a heap. “What!” he said, “to renounce a city like this and to enter the holy life as soon as the chance came, this is truly a noble thing!” Asking the way of some drunken fellow, he went to find Hatthipāla. When Hatthipāla saw that he was coming to the skirt of the forest, he went out to meet him. And poised in the air he declared the Dharma to his company. Then he led them to the hermitage where he received the whole band into the Saṇgha. In the same manner six other kings joined them. These seven kings renounced their wealth. The hermitage, 36 leagues in extent, was filling continually.

When some had thoughts of lust or any such thing, he would declare the Dharma to them and teach them about the Perfections (the Ten Perfections: generosity, virtue, renunciation, wisdom, energy, patience, honesty, determination, loving-kindness, and equanimity) and meditative bliss (samadhi). They then usually developed a state of meditative absorption (jhāna). Two-thirds of them were reborn in Brahma’s world. The other third was divided into three parts. One part was born in Brahma’s world, one in the six sense heavens, and one—having performed a seer’s mission—was born in the world of men. Thus they enjoyed these rebirths because of their merit. Thus Hatthipāla’s teaching saved all from hell, from animal birth, from the world of ghosts, and from being embodied as a Titan. (These are the inauspicious rebirths.)

End of story in the present...