Jataka 515

Sambhava Jātaka

The Story of Sambhava

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story has two interesting elements. The first is the ongoing quest of Sucīrata. He travels throughout all of India looking for an answer to the question, “What is good and true?” He does not find anyone who can answer the question. Eventually he lands in the kingdom of Benares where there is a family of sages.

However, one after another these sages prove to be having affairs with another man’s wife! This disturbs their minds in such a way that they cannot answer the question. Apparently, you cannot answer a question about what is good and true if you, yourself, are not good and true. But fortunately for Sucīrata, he finds a young man who is, of course, the Bodhisatta. He finally gets an answer to his question.

“This rule.” The Master told this story when he was at Jetavana. It is about the Perfection of Wisdom. The circumstances leading to the introductory story will be set forth in the Mahāummagga Birth (Jātaka 546).

Once upon a time a King called Dhanañjaya Korabya reigned in the city of Indapatta in the Kuru kingdom. A brahmin named Sucīrata was his priest and adviser in things temporal and spiritual. The King ruled his kingdom righteously in the exercise of almsgiving and other good works. Now one day he prepared a question about the service of Truth, and having seated the brahmin Sucīrata and paid him due honor, he put his question to him in the form of four stanzas:

This rule and lordship I disdain,

Sucīrata, for I would fain

Be great, and o’er the wide world reign.

By right alone—wrong I eschew—

For whatsoe’er is good and true

Kings above all men should pursue.

By this forever free from blame,

Here and hereafter, we may claim

Midst gods and men a glorious name.

Know, brahmin, that I gladly do

Whate’er is deemed both good and true,

So pray, when asked, declare to me

The Good and True, what they may be.

Now this was a profound question, falling within the range of a Buddha. This is a question one should put to an Omniscient Buddha, and, failing him, to a Bodhisatta who is seeking the Gift of Omniscience. But Sucīrata, not being a Bodhisatta, could not answer the question. And so, rather than pretend an air of wisdom, he confessed his incompetency in the following stanza:

No one but Vidhura, O King,

Has power to tell this wondrous thing,

What is, my lord, the Good and True,

That you are ever glad to do.

(Vidhura was the chaplain of the King of Benares.)

The King, on hearing his words, said, “Go then, brahmin, at once,” and he gave him a present to take with him. And in his eagerness to send him off, he repeated this stanza:

Lo! straight this weight of gold, my friend,

By you to Vidhura I send,

A gift for sage who best can show

The Good and True that I would know.

And with these words he gave him a tablet of gold worth a hundred thousand gold coins on which to write the answer to the question. The King provided a chariot to travel in, an army to escort him, and a present to offer, and straightway he sent him off.

Departing from the city of Indapatta, he did not go straight to Benares. He first visited all the places where sages dwell. And not finding anyone in all India who could answer the question, he gradually approached Benares. Taking up his residence there, he went with a few followers to the house of Vidhura at the time of the early meal. And having announced his arrival, he was invited in and found Vidhura at breakfast in his own house.

The Master, to make the matter clear, repeated the seventh stanza:

Then in haste did Bhāradvāja extend

His way to Vidhura, and found his friend

Sitting at home, and ready to partake

Of simple fare, his early fast to break.

(Bhāradvāja is the family name of Sucīrata.)

Now Vidhura was a friend from his youth. He had been educated in the family of the same master. So after partaking of the meal with him, when breakfast was over and Sucīrata was comfortably seated, Vidhura asked, “What brings you here, friend?” He told him why he had come and repeated the eighth stanza:

I come at far-famed Kuru King’s behest,

Sprung from Yudhiṭṭhila, and this his quest,

To ask you, Vidhura, to tell to me

The True and Good, what it may surely be.

(The Kurus were descended from Yudhiṭṭhila.)

At that time the brahmin, thinking to collect the ideas of a number of people pursuing his quest, was like one piling them up as if they were a Ganges flood. So stating the case he repeated the ninth stanza:

O’erwhelmed by such a mighty theme

As ‘twere by Ganges’ flooded stream,

I cannot tell what this may be,

The Good and True you seek from me.

And so saying he added, “I have a clever son, far wiser than I am. He will make it clear to you. Go to him.” And he repeated the tenth stanza:

A son I have, my very own,

‘Mongst men as Bhadrakāra known.

Go seek him out, and he’ll declare

To you what Truth and Goodness are.

On hearing this, Sucīrata left Vidhura’s house and went to the dwelling of Bhadrakāra. He found him seated at breakfast among his people.

The Master, to clear up the matter, repeated the eleventh stanza:

Then Bhāradvāja hastily

To Bhadrakāra’s home did flee,

Where amidst friends, all gathered round,

Seated at ease the youth was found.

On his arrival there he was hospitably received by the youth Bhadrakāra with the offer of a chair and gifts. And taking his seat, he asked why he had come. He repeated the twelfth stanza:

I come at far-famed Kuru King’s behest,

Sprung from Yudhiṭṭhila, and this his quest,

To ask you, Bhadrakāra, to show me

Goodness and Truth, what they may surely be.

Then Bhadrakāra said to him, “Just now, sir, I am involved in an intrigue with another man’s wife. My mind is not at ease, so I cannot answer your question. But my young brother Sañjaya has a clearer intellect than I have. Ask him, and he will answer your question.” And to send him there, he repeated two stanzas:

Good venison I leave, a lizard to pursue,

How should I know anything about the Good and True?

I’ve a young brother, you must know,

Named Sañjaya. So, brahmin, go

And seek him out, and he’ll declare

To you what Truth and Goodness are.

He at once set out for the house of Sañjaya where he was welcomed by him. And on being asked why he had come he told him the reason.

The Master, to make the matter clear, uttered two stanzas:

Then Bhāradvāja hastily

To home of Sañjaya did flee,

Where amidst friends, all gathered round,

Seated at ease the youth was found.

I come at far-famed Kuru King’s behest,

Sprung from Yudhiṭṭhila, and this his quest,

To ask you, Sañjaya, to show to me

Goodness and Truth, what they may surely be.

But Sañjaya also was engaged in an intrigue and said to him, “Sir, I am in pursuit of another man’s wife, and going down to the Ganges, I cross over to the other side. Evening and morning as I cross the stream, I am in the jaws of death. Therefore, my mind is disturbed, and I shall not be able to answer your question. But my young brother Sambhava, a boy of seven years, is a hundred thousand times superior to me in knowledge. He will tell you. Go and ask him.”

The Master, to make the matter clear, repeated two stanzas:

Death opens wide his jaws for me,

Early and late. How tell to thee

Of Truth and Goodness, what they be?

I’ve a young brother, you must know,

Called Sambhava. So, brahmin, go,

And seek him out. He will declare

To you what Truth and Goodness are.

On hearing this Sucīrata thought, “This question must be the most wonderful thing in the world. I think that no one is able to answer it.” And so thinking he repeated two stanzas:

This marvel strange does not like me,

Not sire or sons, none of the three,

Knows how to solve this mystery.

If they all fail, can this mere youth

Know about Goodness and of Truth?

On hearing this Sañjaya said, “Sir, do not regard young Sambhava as a mere boy. If there is no one else who can answer your question, go and ask him.” And, describing the qualities of the youth by similes that illustrated the case, he repeated twelve stanzas:

Ask Sambhava don’t scorn his youth,

He knows right well and he can tell

Of Goodness and of Truth.

As the clear moon outshines the starry host,

Their meaner glories in his splendor lost.

E’en so the stripling Sambhava appears

To excel in wisdom far beyond his years.

Ask Sambhava, don’t scorn his youth,

He knows right well and he can tell

Of Goodness and of Truth.

As charming April doth all months outvie

With budding flowers and woodland greenery.

E’en so the stripling Sambhava appears

To excel in wisdom far beyond his years.

Ask Sambhava, don’t scorn his youth,

He knows right well and he can tell

Of Goodness and of Truth.

As Gandhamādana, its snowy height

With forest clad and heavenly herbs delight,

Diffusing light and fragrance all around,

For myriad gods a refuge sure is found.

E’en so the stripling Sambhava appears

To excel in wisdom far beyond his years.

Ask Sambhava, don’t scorn his youth,

He knows right well and he can tell

Of Goodness and of Truth.

As glorious fire, ablaze thro’ some morass

With wreathing spire, insatiate, eats the grass

Leaving a blackened path, where’er it pass.

Or as an oil-fed flame in darkest night

On choicest wood does whet its appetite,

Shining conspicuous on some distant height,

E’en so the stripling Sambhava appears

To excel in wisdom far beyond his years.

Ask Sambhava, don’t scorn his youth,

He knows right well and he can tell

Of Goodness and of Truth.

An ox by strength, a horse by speed,

Displays his excellence of breed,

A cow by milk in copious flow,

A sage by his wise words we know.

E’en so the stripling Sambhava appears

To excel in wisdom far beyond his years.

Ask Sambhava, don’t scorn his youth,

He knows right well and he can tell

Of Goodness and of Truth.

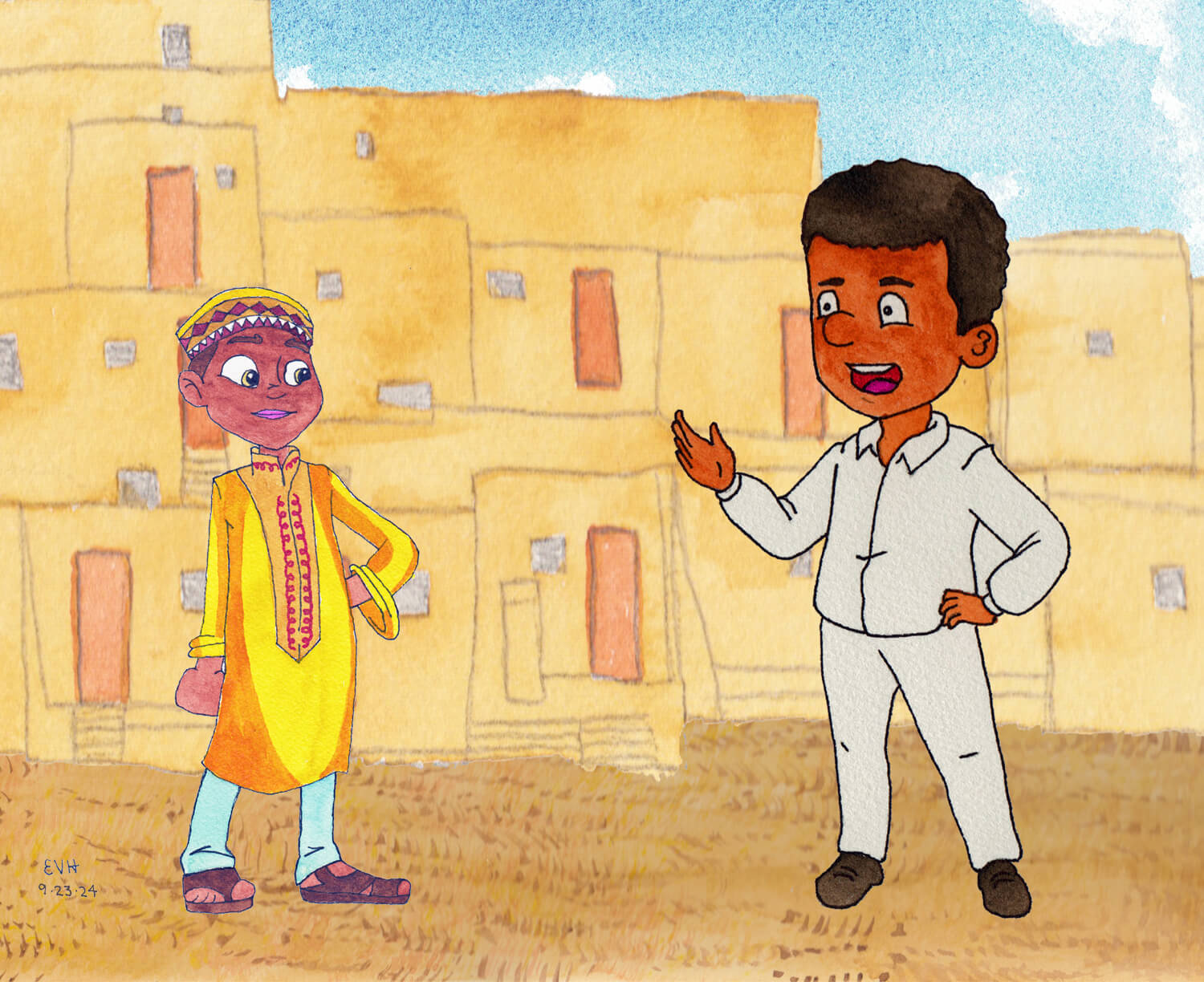

While Sañjaya was singing the praises of Sambhava, Sucīrata thought, “I will find out by putting the question to him.” So he asked, “Where is your young brother?” Then he opened the window, and stretching out his hand, he said, “You see that boy with a complexion like gold playing with other youths in the street before the door of the mansion? That is my young brother. Go up to him and ask him. He will answer your question with all the charm of a Buddha.” Sucīrata, on hearing his words, descended from the mansion. He went up to the boy when he was standing with his garment loose and thrown over his shoulder and picking up some dirt with both hands.

The Master, to explain the matter, repeated a stanza:

Then Bhāradvāja hastily

To home of Sambhava did flee,

And there out in the public way

The little boy was found at play.

The Great Being, when he saw the brahmin come and stand before him, asked, “Friend, what brings you here?” He replied, “Dear youth, I have been wandering through all India, and I have not been able to find anyone capable of answering the question I put to him. So now I have come to you.” The boy thought, “There is a question, they say, that has not been decided in all India. He has come to me. I am old in knowledge.” And becoming ashamed, he dropped the dirt that he held in his hand, readjusted his garment and said, “Brahmin, ask on, and I will tell you with the fluent mastery of a Buddha.” And in his omniscience, he invited him to ask his question. Then the brahmin asked his question in the form of a stanza:

I come at far-famed Kuru King’s behest,

Sprung from Yudhiṭṭhila, and this his quest,

To ask you, Sambhava, to show to me

Goodness and Truth, what they may surely be.

Figure: Sucīrata asks the boy his question.

What he wanted became clear to Sambhava, as if it were the full moon in the middle of the sky. “Then listen to me,” he said. And answering the question as to the Service of Truth he uttered this stanza:

I’ll tell you, sir, and tell it right,

E’en as a man of wisdom might,

The King shall know the Good and True,

But who knows what the King will do?

And as he stood in the street and taught the Truth with a voice as sweet as honey, the sound spread over the whole of the city of Benares, to twelve leagues on every side Then the King and all his viceroys and other rulers assembled together, and the Great Being in the midst of the multitude set forth his exposition of the Truth.

Having promised in this stanza to answer the question, he now gave the answer as to the Service of Truth:

In answer to the King, Sucīrata, proclaim,

“Tomorrow and Today are never quite the same.

I bid you then, O King Yudhiṭṭhila, be wise

And prompt to seize whate’er occasion may arise.”

I gladly would have you, Sucīrata, suggest

A thought in which his mind may profitably rest,

“All wicked ways a king should carefully eschew,

Nor, like bewildered fool, an evil course pursue.”

The loss of his own soul he never should transgress,

Or e’er be guilty of deeds of unrighteousness,

Himself ne’er be engaged in any evil way,

Or ever in wrong path a brother lead astray.

These points to carry out whoe’er does rightly know,

Like waxing moon, as king in fame does ever grow.

A shining light to friends and dear unto his kin,

And, when his body fails, the sage to heaven will win.

In this way the Great Being, like making the moon rise in the sky, answered the brahmin’s question with all the mastery of a Buddha. The people roared and shouted and clapped their hands. And there arose a thousand cries of applause with great wavings of cloths and snapping of fingers. And they cast off the trinkets on their hands. And the value of what they threw down amounted to about a crore (10 million rupees). And the King of Benares—in his joy—paid him great honor. And Sucīrata, after offering him a thousand gold coins, wrote down the answer to the question with vermilion on a golden tablet. Then he returned to the city of Indapatta where he told the King the answer about the Service of Truth. And the King ruled in righteousness, finally attaining to heaven.

At the end of the lesson the Master said, “Not only now, brothers, but formerly too, the Tathāgata was great in answering questions.” Then he identified the birth: “At that time Ānanda was King Dhanañjaya, Anuruddha was Sucīrata, Kassapa Vidhura, Moggallāna Bhadrakāra, Sāriputta the youth Sañjaya, and I was the wise Sambhava.”