Jataka 518

Paṇḍara Jātaka

Paṇḍara, The Snake King

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is an interesting story with a twist. In it there are two traditional enemies. One of them convinces a sham ascetic to betray the other one. I won’t give it away, but it has a nice ending, at least for two of the three of them.

“No man that lets.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about how Devadatta told a lie, and how the earth opened and swallowed him up. At that time, when Devadatta was being condemned by the monks, the Master said, “Not now only, brothers, but in the past, too, Devadatta told a lie and was swallowed up by the earth.” And so saying, he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was the King in Benares, 500 trading folk took ship and set sail. And on the seventh day—when they were out of sight of land—they were wrecked in mid-ocean, and all but one man became food for the fish. Due to a favorable wind, this man reached the port of Karambiya. He landed naked and destitute. He went about the place, begging for alms. The people thought, “Here is an ascetic. He is happy and contented with little.” They showed him every hospitality. But he said, “I have enough to live on,” and when they offered him under and upper garments, he would have none of them. They said, “No ascetic can go beyond this in the way of contentment.” And being even more pleased with him, they built him a hermitage for him, and he went by the name of the Karambiya Ascetic.

When he was living here, he met with great honor and gain. Both a snake king and a Garuḍa king came to pay their respects to him. (Garuḍas are bird deities. See Jātaka 327.) The name of the snake king was Paṇḍara. Now one day the Garuḍa king went to the ascetic, and after saluting him, he took his seat on one side. He said, “Sir, when our people attack snakes, many of them die. We do not know the right way to seize snakes. There is said to be some mystery in the matter. You could, perhaps, conjure the secret out of them.” “All right,” said the ascetic.

Once the Garuḍa king had taken his leave and departed, the snake king arrived, and with a respectful salutation, he took a seat. He asked him, “King-snake, the Garuḍas say that when they seize you, many of them are killed. When they attack you, how can they do this securely?” “Sir,” he replied, “This is a secret. If I were to tell it, I would bring about the destruction of all my kinsfolk.” “What, do you really suspect me of telling someone else? I’ll tell no one. I only ask to satisfy my own curiosity. You may trust me and tell me without the slightest fear.” The snake king promised to tell him and took his leave.

On the next day the ascetic again asked him. Then, too, he did not tell him. But on the third day, when the snake king had taken his seat, the ascetic said, “Today is the third day that I have asked you. Why do you not tell me?” “I am afraid, sir, that you might tell someone else.” “I’ll not say a word to any creature. Tell me without any fear.” The snake made him promise to tell no one. He said, “Sir, we make ourselves heavy by swallowing very big stones and lie down. And when the Garuḍas come, we open our mouths wide and show our teeth. Then we fall upon them. They seize us by the head, and when they try to lift us up from the ground, as heavy as we are, water streams from them, and they drop down dead in the middle of it. In this way many Garuḍas perish. When they attack us, why in the world do they seize us by the head? If the foolish creatures would seize us by the tail and hold us head down, they could force us to disgorge the stones we have swallowed. This would make us light, and they could carry us off.” In this way the snake revealed his secret to this wicked fellow.

Then, when the snake had gone away, the Garuḍa king arrived. He saluted Karambiya Ascetic and asked, “Well! sir, have you learned his secret from the snake king?” “Yes, Sir,” he said, and he told him everything just as it was told him. On hearing it, the Garuḍa said, “The snake king has made a great mistake. He should not have told anyone how to destroy his kinsfolk. Well, today I must first raise a Garuḍa wind (by flapping of a Garuḍa’s wings) and seize him.” So, raising a wind, he seized Paṇḍara the snake king by the tail and held him head downward. He made him disgorge the stones he had swallowed, then he flew up into the air with him. Paṇḍaraka, as he was suspended head downwards in the air, sorely lamented, crying, “I have brought sorrow upon myself,” and he repeated these stanzas:

The man that lets his secret thought be known,

Random of speech, to indiscretion prone,

Poor fool, at once is overcome by fear,

As I king snake am by a bird o’erthrown.

The man who in his folly could betray

The thought that he should hide from light of day,

By his rash speech is overcome by fear,

As I king snake fall to this bird a prey.

No comrade ought his inmost thoughts to share,

The best of friends often most foolish are,

And if, too, wise, of treachery beware.

I trusted him alas! for was not he

A holy man, of strict austerity?

My secret I revealed, the deed is done

And now I weep for very misery.

Into my confidence the wretch did creep,

Nor could I any secret from him keep,

From him the danger that I dread has come,

And now for very misery I weep.

Judging his friend as faithful to the core

And moved by fear, or the strong love he bore,

To some vile wretch his secret one betrays

And is o’erthrown, poor fool, to rise no more.

Whoe’er proclaims in evil company

The secret thought that still should hidden lie,

’Mongst men is counted as a poison snake,

“From such a one, pray, keep aloof,” they cry.

Fair women, silken robes and sandal wood,

Garlands and perfumes, even drink and food,

Yea all desires—if only you, O bird,

Come to our aid—shall be by us eschewed.

In this way Paṇḍaraka, suspended in the air head downwards, uttered his lament in eight stanzas.

The Garuḍa, hearing his lamentation, reproved him and said, “King snake, after divulging your secret to the ascetic, where will you lament now?” And he uttered this stanza:

Of us three creatures living here, pray name

The one that rightly should incur the blame.

Nor priest nor bird, but foolish deed of thine,

O snake, this brought you to this depth of shame.

On hearing this Paṇḍaraka repeated another stanza:

The priest, I thought, must be a friend to me,

A holy man, of strict austerity,

My secret I betrayed, the deed is done,

And now I weep for very misery.

Then the Garuḍa repeated four stanzas:

All creatures born into this world must die,

Yet wisdom’s ways her children justify,

By knowledge, justice, self-restraint and truth

A man at length achieves his purpose high.

Parents are kind to all the kin above,

No third there is to show us equal love,

Not e’en to them betray a secret thought,

Lest uncertainty they should traitors prove.

Parents and kin of every degree,

Allies and comrades all may friendly be,

To none of them entrust your hidden thought,

Or you will later rue their treachery.

A wife may youthful be and good and fair,

Own troops of friends, and children’s love may share,

Not e’en to her entrust your hidden thought,

Or of her treachery you must beware.

Then follow these stanzas:

His secret no man should disclose, but guard like treasure trove,

Disclosure of a secret thing no wise man would approve.

Wise men to woman or a foe their secrets ne’er betray,

Trust not the slaves of appetite, creatures of impulse they.

Whoe’er reveals his secret thought to one not overwise,

Fears the betrayal of his trust and at his mercy lies.

All such as know the secret thing that you should rather hide,

Threaten your peace of mind, to none that secret thing confide.

By day to your own self alone the secret dare to name,

But venture not at dead of night that secret to proclaim.

For close at hand, be sure, there stand men ready to betray

The slightest word they may have heard, so trust them not, I pray.

These five stanzas will appear in the Problem of the Five Sages in the Ummagga Birth (Jātaka 546).

Then follow these stanzas:

As some huge city fenced on every side

With moat, of iron wrought, has long defied

All entrance of a foe to Fairy Land,

So e’en are they that do their counsels hide.

Who by rash speech to secrets give no clue,

But ever steadfast to themselves are true,

From them all enemies do keep aloof,

As men flee far when deadly snakes pursue.

When the Truth had been thus proclaimed by the Garuḍa, Paṇḍaraka said:

A tonsured, nude ascetic left his home

And seeking alms did through the country roam,

To him my secret I alas! did tell,

And straight from happiness and virtue fell.

What line of conduct should a priest pursue,

What vows take on him, and what faults eschew?

How free himself from his besetting sin,

And at the last a heavenly mansion win?

The Garuḍa said:

By patience, self-restraint, long-suffering,

By calumny and ire abandoning,

Thus may a priest get rid of every sin,

And at the last a heavenly mansion win.

Paṇḍaraka, on hearing the Garuḍa king declare the Truth, begged for his life and repeated this stanza:

As mother gazing on her baby boy

Is thrilled in every limb with holy joy,

So upon me, O king of birds, bestow

That pity mothers to their children show.

Then the Garuḍa granted him his life, repeating another stanza:

O snake, today from death I set you free,

Of kinds of children there are only three,

Pupil, adopted child, and true-born son,

Of these rejoice that you are surely one.

So saying, he landed from the air and placed the snake on the ground.

The Master, to make the matter clear, repeated two stanzas:

The bird, so saying, straight released his foe

And gently bore him to the earth below,

“Set free today, go, safe from danger dwell

In water or on land. I’ll guard you well.

As a skilled leech to men with sickness cursed,

Or a cool tank to those that are at thirst,

As house that shelters from a chilling frost,

So I a refuge prove to you, when lost.”

And saying, “Be off,” he let him go, and the snake disappeared to the land of the nāgas (snakes).

But the bird, returning to the land of the Garuḍas, said, “The snake Paṇḍaraka has won my confidence under oath and has been let loose by me. I will now put him to the test, to see what his feelings are towards me.” He raised a Garuḍa wind, and when he saw it, the snake king thought that the Garuḍa king must have come to seize him. So he assumed a form that stretched to a thousand fathoms. He made himself heavy by swallowing stones and sand. Then he lay down, keeping his tail beneath him and raising the hood on his head as if to bite the Garuḍa king. On seeing this the Garuḍa repeated another stanza:

O snake, you made your peace with an old enemy,

But now you show your fangs. Why comes this fear to thee?

On hearing this the snake king repeated three stanzas:

Ever suspect a foe, or trust your friend as staunch,

Security breeds fear, to kill you root and branch.

What! trust the man with whom one quarreled long ago!

No! Stand upon your guard. No one can love his foe.

Inspire a trust in all, but put your trust in none,

You were not suspected, be to suspicion prone.

He that is truly wise ought every nerve to strain

That his true nature ne’er may be to others plain.

In this way they talked with each other. But they reconciled and became friendly. Then they repaired to the hermitage of the ascetic.

The Master, to make the matter clear, said,

The godlike graceful pair of them now see,

Breathing an air of holy purity,

Like steeds well matched neath equal yoke they ran,

To seek the dwelling of that saintly man.

Regarding this the Master uttered another stanza:

Then to the ascetic straight king snake did go,

And thus Paṇḍaraka addressed his foe,

“Know that today, all danger past, I’m free,

But ‘tis not due to love of yours for me.”

Then the ascetic repeated another stanza:

To that bird king, I solemnly declare,

I greater love than e’er to you did bear,

Moved by affection for that royal bird,

I of set purpose, not through folly, erred.

On hearing this, the snake king repeated two stanzas:

The man that looks at this world and the next,

Ne’er finds himself with love or hatred vexed,

‘Neath garb of self-restraint you soon would hide

But lawless acts that holy garb belied.

You, seeming noble, are with meanness stained,

And, as ascetic clad, are unrestrained.

By nature with ignoble thoughts accursed,

You in all kinds of dreadful act are versed.

So to reprove him, he uttered this stanza, reviling him:

Informer, traitor, that would slay

A guileless friend, be your head riven

By this my Act of Truth, I pray,

Piecemeal, all into fragments seven.

So before the eyes of the snake king, the head of the ascetic was split into seven pieces, and at the very spot where he was sitting, the ground was cleft asunder. And, disappearing into the earth, he was re-born in the Avīci hell, and the snake king and the Garuḍa king returned each to his own abode.

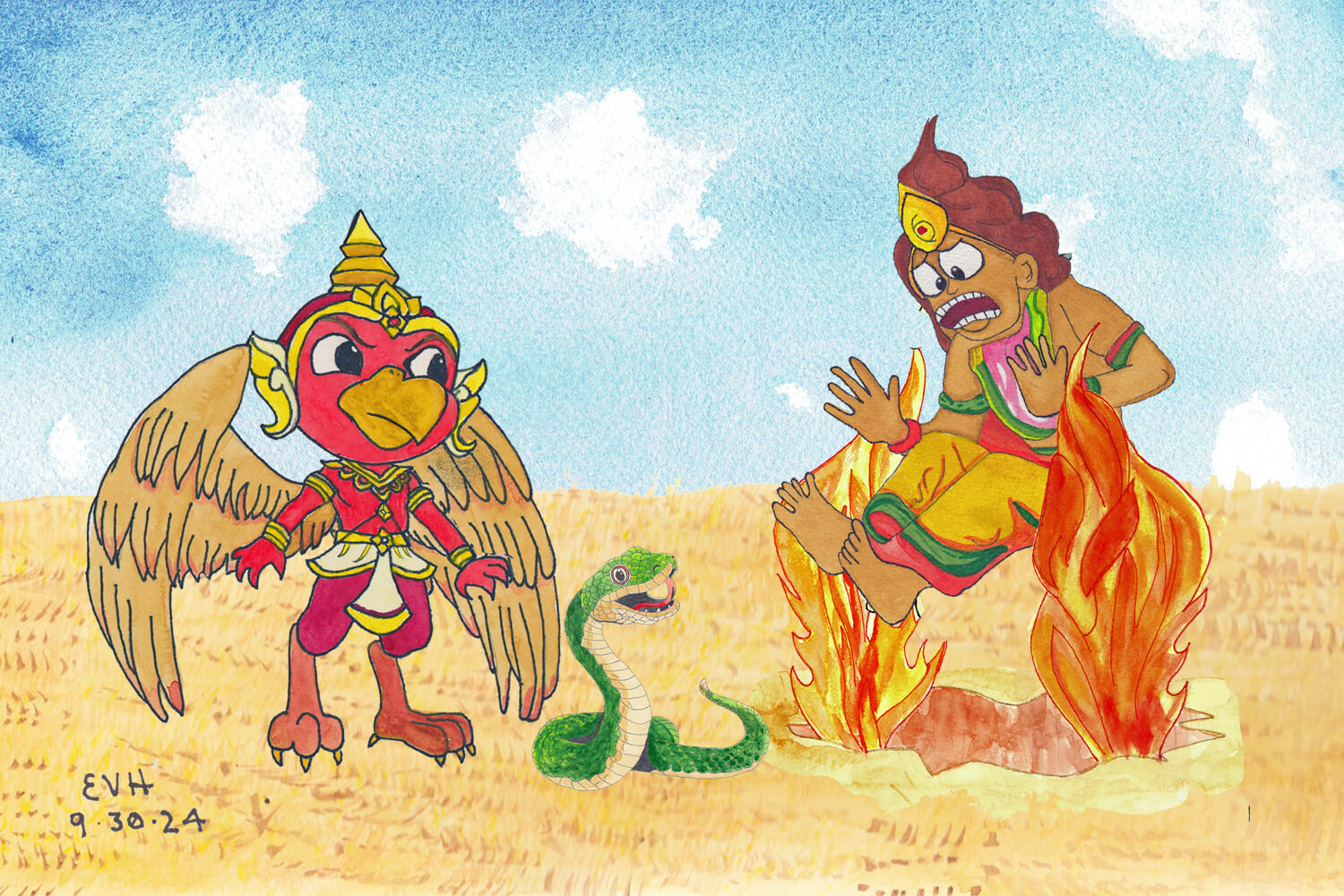

Figure: Disappearing into the earth.

The Master, to make clear the fact that he had been swallowed up by the earth, repeated the last stanza:

Therefore I say, friends ne’er should treacherous be,

Then a false friend worse man is none to see.

Buried in earth the venomous creature lies,

And at the snake king’s word the ascetic dies.

The Master here ended his discourse and said, “Not now only, brothers, but in the past, too, Devadatta told a lie and was swallowed up by the earth.” Then he identified the birth: “At that time the ascetic was Devadatta, the snake king was Sāriputta, and I was the Garuḍa king.”