Jataka 522

Sarabhanga Jātaka

The Breaking Arrow

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

Moggallāna was one of the Buddha’s two chief disciples, and the story of his death is one of the most iconic in the Pāli Canon. As you will see in the story, Moggallāna had bad karma from a previous life, and even he was not able to prevent it from manifesting. Many times he was able to use his psychic powers—for which he was famous—to elude his assailants. But as stated here, even he was finally unable to get away from them, and he was killed. This Jātaka gives a long account of Moggallāna in a previous birth.

“Wearing rings and gallant.” The Master told this story while living in the Bamboo Grove (Veluvana). It is about the death of the Elder, the Great Moggallāna. The Elder Sāriputta (the other of the Buddha’s two chief disciples), after gaining consent from the Tathāgata when he was living at Jetavana, went and died in the village of Nāla. He died in the very room where he was born.

The Master, on hearing of Sāriputta’s death, went to Rājagaha and took up his abiding in the Bamboo Grove. Moggallāna lived there on the slopes of Isigili (Mount of Saints) at the Black Rock. By attaining perfection in supernatural powers, he was able to travel to heaven and hell. In the god world, he saw one of the disciples of the Buddha enjoying great power. In the world of men, he saw one of the disciples of the heretics suffering great agony. When he returned to the world of men, he told them how in a certain god-world such and such a lay brother or sister was re-born and enjoying great honor, and how among the followers of the heretics such and such a man or woman was reborn in hell or some other state of suffering. People gladly accepted his teaching and rejected that of the schismatics. Great honor was paid to the disciples of Buddha, while that paid to the schismatics fell away.

There were those who developed a grudge against the Elder. They said, “As long as this fellow is alive, there will be divisions among our followers, and the honor paid to us will fall away. We will have him killed.” They bribed a brigand who guarded the aesthetics a thousand gold coins to put the Elder to death. He resolved to kill the Elder and went with a great following to Black Rock. When Moggallāna saw him coming, the Elder used his magic power to fly up into the air and disappear. The brigand, not finding the Elder that day, returned home. He went back day after day for six consecutive days. But the Elder always used his magic to disappear in the same way.

On the seventh day a foolish act committed in the past by the Elder manifested its consequences. As a result, there arose a chance for mischief. The story goes that once upon a time, according to what his wife said, he wanted to put his father and mother to death. He took them in a carriage to a forest. There he pretended that they were being attacked by robbers. He struck and beat his parents. Because their eyesight was poor, they were unable to see objects clearly, and they did not recognize their son. Thinking there were robbers they said, “Dear son, some robbers are killing us! Make your escape!” They thought of him only. He thought, “Even though they are being beaten by me, it is only for me that they grieve. I am acting shamefully.” So he reassured them, and pretending that the robbers had been chased away, he stroked their hands and feet, saying, “Dear father and mother, do not be afraid. The robbers have fled.” Then he returned them to their house.

For a long time, this action had not incurred any consequences. But biding its time, like a core of flame hidden under ashes, it caught up to the man and seized on him when he was reborn for the last time. Because of his action, the Elder was finally unable to fly up into the air. The magic power that once could quell Nanda and Upananda and cause Vejayanta to tremble (Nanda and Upananda were two kings of the Nāgas, and Vejayanta was the palace of Indra) was useless. The brigand crushed all his bones and subjected him to the straw and meal torture (they beat him). When they thought he was dead, they went off with his followers.

But the Elder recovered consciousness. He clothed himself with Meditation as a garment. He flew up into the presence of the Master. He saluted him and said, “Holy sir, my sum of life is exhausted. I will die.” And having gained the Master’s consent, he died then and there.

At that instant the six god-worlds were in a general state of commotion. “Our Master,” they cried, “is dead.” They arrived, bringing incense and perfume and wreaths breathing divine odors and all kinds of wood. The funeral pile was made of sandalwood and ninety-nine precious things. (It is not clear what the “ninety-nine precious things” are.) The Master, standing near the Elder, ordered his remains to be cremated, and for the space of a league all round about the spot where the body was burned, flowers rained down on it. Men and gods stood together, and for seven days they held a sacred festival. The Master had the relics of the Elder gathered and had erected a shrine in a gabled chamber in the Bamboo Grove.

At that time they raised the topic in the Dharma Hall, saying, “Sirs, Sāriputta, because he did not die in the presence of the Tathāgata, has not received great honor at the hands of the Buddha. But the Great Elder Moggallāna, because he died near the Master, has had great honor paid to him.” The Master arrived and asked the brothers what they were discussing. When he heard what it was, he said: “Not only now, brothers, but in the past also, Moggallāna received great honor at my hands.” And, so saying, he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was conceived by the brahmin wife of the royal chaplain. At the end of ten months, he was born. It was early in the morning. At that moment there was a blaze of all kinds of arms in the city of Benares for the space of twelve leagues. The priest, on the birth of the boy, stepped out of doors and looked up to the sky to divine his son’s destiny. He saw that this boy, because he was born under a certain conjunction in the heaven, would be the best archer in all India.

So he went to the palace where he asked after the King’s health. The King replied, “How, my master, can I be well. On this day there is a blaze of weapons throughout my dwelling-place.” The priest said, “Fear not, sire. This is not only in your house, but throughout all the city is this blaze of arms to be seen. This is because a boy is born today in our house.” “What, master, will be the result of the birth of a boy under these conditions?” “Nothing, sire, but he will prove to be the chief archer in all India.” “Well, master, then watch over him, and when he has grown up, present him to us.” And so saying, he ordered a thousand gold coins to be given to the priest as the price of his support.

The priest took the money and went home. And on the naming-day of his son, because of the blaze of arms at the moment of his birth, he called him “Jotipāla.” He was reared in great state, and at the age of 16 he was extremely handsome. Then his father, observing his personal distinction, said, “Dear son, go to Takkasilā University and receive instruction in all learning at the hands of a world-famous teacher.” He agreed to do so. And, taking his teacher’s fee, he bid his parents farewell and went off.

He presented his fee of one thousand gold coins and set about acquiring his instruction. In the course of just seven days he had reached perfection. His master was so delighted with him that he gave him a precious sword and a bow of ram’s horn and a quiver. Both were deftly joined together. He also gave him his own coat of mail and a diadem (a symbol of authority). He said, “Dear Jotipāla, I am an old man. Now you should train these pupils.” He handed 500 pupils over to him. The Bodhisatta took everything with him and said good-bye to his teacher.

He returned to Benares and went to see his parents. His father, on seeing him standing respectfully before him, said, “My son, have you finished your studies?” “Yes, sir.” On hearing his answer, he went to the palace and said, “My son, sire, has completed his education. What is he to do?” “Master, let him wait on us.” “What do you decide, sire, about his expenses?” “Let him receive a thousand gold coins every day.” He readily agreed to this, and returning home he called his boy to him and said, “Dear son, you are to serve the King.”

From then on, he received a thousand gold coins every day, and he attended to the King. But the King’s attendants were offended. “We do not see that Jotipāla does anything, and he receives a thousand gold coins every day. We would like to see an example of his skill.” The King heard what they said and told the priest. He said, “All right, sire,” and he told his son. “Very well, dear father,” he said, “on the seventh day from this I will show them. Let the King assemble all the archers in his domain.” The priest went and repeated what he had said to the King.

The King had all his archers gathered by beat of the drum throughout the city. When they were assembled, they numbered 60,000. When the King heard that they had assembled, he said, “Let all who live in the city witness the skill of Jotipāla.” And making a proclamation by the beat of a drum, he had the palace yard prepared. Then followed by a great crowd, he took his seat on a splendid throne. And once he had summoned the archers, he sent for Jotipāla.

Jotipāla put the bow and quiver and coat of mail and diadem, which had been given to him by his teacher, underneath his garment. He had his sword carried for him. Then he went before the King in his ordinary clothing and stood respectfully on one side. The archers thought, “Jotipāla, they say, has come to give us an example of his skill. But he is here without a bow. Evidently, he will want to receive one at our hands.” But they all agreed that they would not give him one.

The King addressed Jotipāla and said, “Give us proof of your skill.” So he had a tent-like screen thrown around about him. And taking his stand inside it and doffing his cloak, he put on his armor. He got into his coat of mail and fastened the diadem on his head. Then he fixed a string the color of coral on his ram’s horn bow. Then he bound the quiver on his back and fastened his sword on his left side. He twirled an arrow tipped with adamant (a legendary mineral associated with diamond) on his nail. He threw open the screen and burst forth like a Nāga prince leaping out of the earth. And so, splendidly equipped, he stood and paid homage to the King.

When the crowd saw him, they jumped about and shouted and clapped their hands. The King said, “Jotipāla, give us an example of your skill.” “Sire,” he said, “among your archers are men who pierce like lightning (also called “target cleaving”), able to split a hair and to shoot at a sound (without seeing) and to split a (falling) arrow. Summon four of these archers.” The King summoned them. The Great Being set up a pavilion in a square enclosure in the palace yard. He positioned the four archers at the four corners. He allotted 30,000 arrows to each of them, assigning men to hand the arrows to each one. He himself took an arrow tipped with adamant. He stood in the middle of the pavilion and cried, “O King, let these four archers shoot their arrows all at once to wound me, and I will ward off the arrows.” The King gave the order for them to do so. “Sire,” they said, “we shoot as quick as lightning. We can split a hair and shoot at the sound of a voice (without seeing) and to split a (falling) arrow. But Jotipāla is a mere stripling. We will not shoot him.” The Great Being said, “If you can, shoot me.” “Agreed,” they said, and with one accord they shot their arrows.

The Great Being, striking with his iron arrows in one way or other, made their arrows drop to the ground. Then he threw a wall made of the arrows around him. He piled them together and made a magazine of arrows, fitting each arrow, handle level with handle, stock with stock, feathers with feathers, until the bowmens’ arrows were all spent. And when he saw that it was so, without spoiling his magazine of arrows, he flew up into the air and stood before the King. The people roared, shouting and dancing about and clapping their hands. They threw off their garments and ornaments so that there was treasure lying in a heap to the amount of eighteen crores (one crore is 10 million rupees).

Then the King asked him, “What do you call this trick, Jotipāla?” “The arrow defense, sire.” “Are there any others that know it?” “No one in all India, except myself, sire.” “Show us another trick, friend.” “Sire, these four men stationed at four corners failed to wound me. But if they are posted at the four corners, I will wound them with a single arrow.” But the archers did not dare to stand there. So the Great Being fixed four plantains at the four corners. And fastening a scarlet thread on the feathered part of the arrow, he shot it, aiming at one of the plantains. The arrow struck it and then the second, the third and the fourth, one after another, and then struck the first which it had already pierced, and then it returned to the archer’s hand while the plantains stood encircled with the thread. The people raised shouts of applause. The King asked, “What do you call this trick, friend?” “The pierced circle, sire.” “Show us something more.”

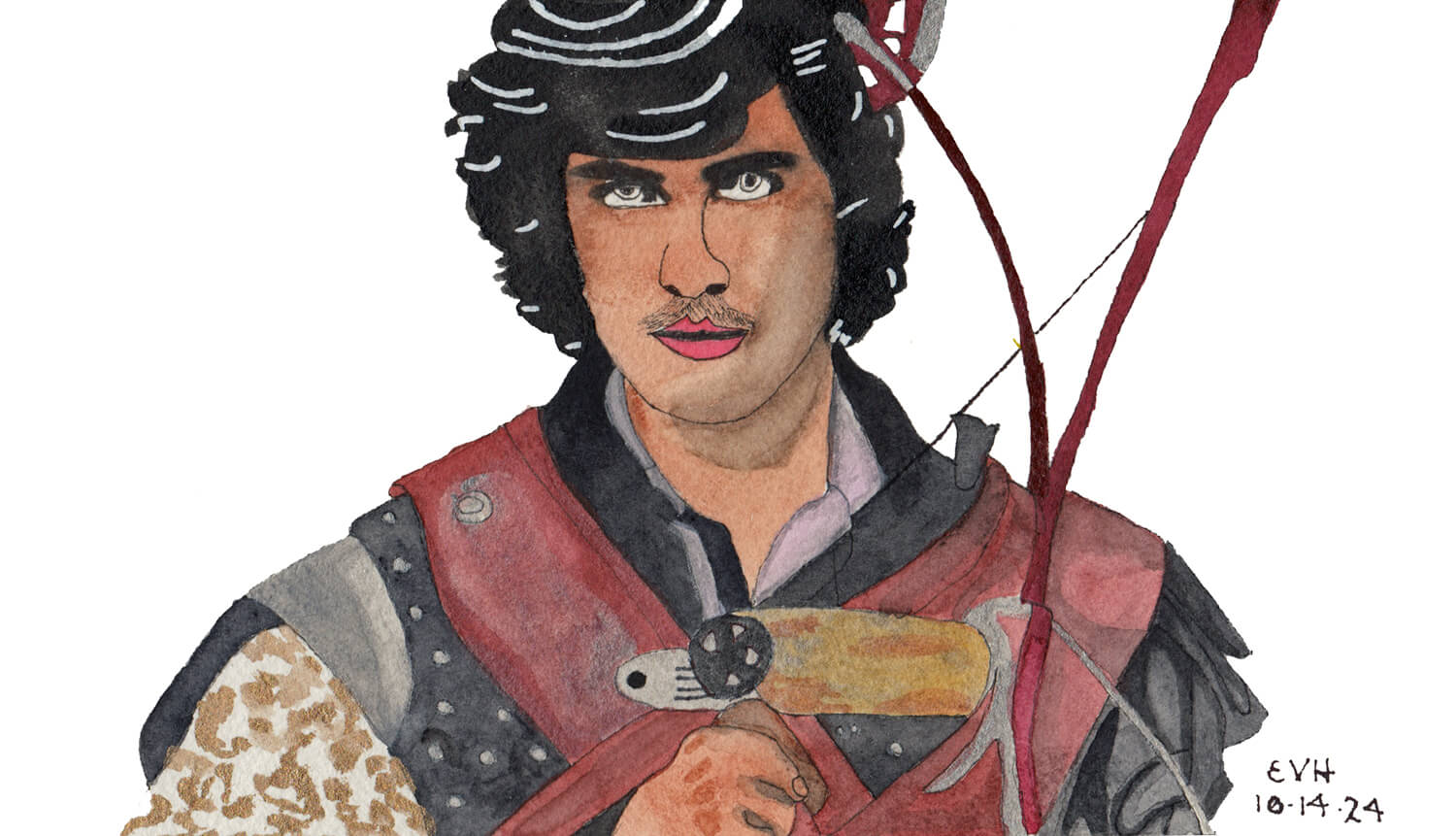

Figure: The finest archer in all of India.

The Great Being showed them the arrow stick, the arrow rope, the arrow plait, and he performed other tricks called the arrow terrace, arrow pavilion, arrow wall, arrow stairs, and the arrow tank. He caused the arrow lotus to blossom and caused it to rain a shower of arrows. In this way he displayed these twelve unrivalled acts of skill. Then he split seven incomparably huge substances. He pierced a plank of fig-wood, eight inches thick, a plank of asana-wood, four inches thick, a copper plate two inches thick, an iron plate one inch thick, and after piercing a hundred boards joined together, one after another, he shot an arrow at the front part of wagons full of straw and sand and planks. The arrow come out the back. And shooting at the back of the wagons, he made the arrow come out the front. He drove an arrow through a space of over a furlong (660 feet or 201 meters) in water and more than two furlongs of earth. He pierced a hair at the distance of half a furlong at the first sign of its being moved by the wind. And when he had displayed all these feats of skill, the sun set.

The King promised him the post of commander-in-chief, saying, “Jotipāla, it is too late today. But tomorrow you shall receive the honor of the chief command. Go and have your beard trimmed and take a bath.” And on that same day he gave him a hundred thousand gold coins for his expenses. The Great Being said, “I have no need of this,” and he gave his lords eighteen crores of treasure and with a large escort, he went to bathe.

After he had had his beard trimmed and had bathed—arrayed in all manner of adornments—he entered his home with great ceremony. After enjoying a variety of dainty foods, he lay down on a royal couch. After he had slept through two watches (there are three “watches” of the night), in the last watch he woke up and sat cross-legged on his couch. He considered the beginning, the middle and the end of his feats of skill. “My skill,” he thought, “in the beginning is evidently death. In the middle it is the enjoyment of defilements. And in the end, it is rebirth in hell. For the destruction of life and excessive carelessness in sensual indulgence causes rebirth in hell. The post of commander-in-chief is given to me by the King. Great power will come to me, and I will have a wife and many children. But if the objects of desire are multiplied, it will be hard to get rid of desire. I will go forth from the world alone and enter the forest. It is right for me to adopt the holy life of an ascetic.”

So the Great Being arose from his couch, and without letting anybody know, he descended from the terrace. He went out by the house door (probably a side door) and into the forest all alone. He stopped at a spot on the banks of the Godhāvarī, near the Kaviṭṭha forest (the Kaviṭṭha is an “elephant apple tree”), three leagues in extent.

Sakka perceived his renunciation of the world. He summoned Vissakamma (the divine architect) and said, “Friend, Jotipāla has renounced the world. A great company will gather around him. Build a hermitage on the banks of the Godhāvarī in the Kaviṭṭha forest and provide them with everything necessary for the ascetic life.” Vissakamma did so.

When the Great Being reached the place, he saw a road for a single foot passenger and thought, “This must be a place for ascetics to live.” And travelling by this road and meeting no one, he entered the hut of leaves. On seeing the requisites for the holy life he said, “Sakka, king of heaven, I think, knew that I have renounced the world.” He removed his cloak, put on an inner and outer robe of dyed bark, and threw an antelope’s skin over one shoulder. Then be bound up his coil of matted locks, shouldered a mound of three bushels of grain, took a mendicant’s staff, and went out of his hut. He climbed up the covered walk and paced up and down it several times. In this way he glorified the forest with the beauty of asceticism. And after performing the Kasiṇa ritual (a Kasiṇa is an object used to attain concentration), on the seventh day of his holy life he developed the eight Attainments (jhānas) and the five Faculties (faith, effort, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom). He lived quite alone, feeding on what he could glean and on roots and berries.

His parents and a crowd of friends and kinsfolk and acquaintances, not seeing him, wandered about disconsolate. Then a certain forester who had seen and recognized the Great Being in the Kaviṭṭha hermitage, told his parents. They informed the King. The King said, “Come, let us go and see him.” And taking the father and mother and accompanied by a great crowd, the King arrived at the bank of the Godhāvarī by the road the forester had pointed out to him. The Bodhisatta went to the riverbank. He seated himself in the air, and after teaching them the Dharma, he brought them all into his hermitage. There, too, he was seated in the air. He revealed to them the misery involved in sensual desires and taught them the Dharma. And all of them, including the King, adopted the holy life.

The Bodhisatta continued to live there, surrounded by a band of ascetics. The news that he was living there was celebrated throughout all India. Kings with their subjects came and took orders at his hands. There was a great assembly of them until they gradually numbered many thousands. The Great Being went to those who reflected on thoughts of lust or the wish to hurt or injure others. And seated in the air before them, he taught him the Dharma and instructed them in the Kasiṇa ritual.

His seven chief pupils were Sālissara, Meṇḍissara, Pabbata, Kāḷadevala, Kisavaccha, Anusissa, and Nārada. (All of these names also occur in Jātaka 423.) And they, abiding in his instruction, attained to ecstatic meditation (jhāna) and reached perfection. By and by the Kaviṭṭha hermitage became overcrowded, and there was no room for the multitude of ascetics to live there. So the Great Being, addressing Sālissara, said, “Sālissara, this hermitage is not big enough for the crowd of ascetics. Go with a company of them and take up your residence near the town of Lambacūlaka in the province of King Caṇḍapajjota.” He agreed to do so. And, taking a company of many thousands, he went there to live.

But as people continued to come and join the ascetics, the hermitage was full once again. The Bodhisatta, addressing Meṇḍissara, said, “On the borders of the country of Suraṭṭha is a stream called Sātodikā. Take this band of ascetics and live on the borders of that river.” And he sent him away. In the same way on a third occasion he sent Pabbata, saying, “In the great forest is the Añjana mountain. Go and settle near there.” On the fourth occasion he sent Kāladevala, saying, “In the south country in the kingdom of Avanti is the Ghanasela mountain. Settle near that.”

Still, the Kaviṭṭha hermitage once again overflowed, even though now there was a company of ascetics numbering many thousands in five different places. And Kisavaccha, asking leave of the Great Being, took up his residence in the park near the commander-in-chief. This was in the city of Kumbhavatī in the province of King Daṇḍaki. Nārada settled in the central province in the Arañjara chain of mountains, and Anusissa remained with the Great Being.

At this time King Daṇḍaki cast out a courtesan from her position because of some misdeed even though in the past, he had honored her. She roamed about on her own until arriving at the park. Seeing the ascetic Kisavaccha, she thought, “Surely this must be Ill Luck. I will get rid of my bad luck on his person, and then I will go and bathe.” She first bit her tooth-stick then spat out a quantity of phlegm. She not only spat on the matted locks of the ascetic, she also threw her tooth-stick at his head. Then she went and bathed.

Calling her to mind, the King decided to restore her to her former position. And reflecting on her misdeed, she concluded that she had recovered her position because she had rid herself of her defilements on the person of Ill Luck.

Not long after this, the King cast out the family priest from his office. Then he went and asked the woman how she had restored her position. So she told him it was from having gotten rid of her offence on the person of Ill Luck in the royal park. The priest went and got rid of his defilements in the same way. He, too, was then reinstated by the King to his office.

Now by and by there was a disturbance on the King’s frontier. He went there with a division of his army to fight. Then the priest asked the King, “Sire, do you wish for victory or defeat?” When he answered, “Victory,” he said, “Well, Ill Luck dwells in the royal park. Go and unload your defilements on his person.” He approved of the suggestion and said, “Let these men come with me to the park and get rid of their defilements on the person of Ill Luck as well.” He went into the park, nibbled his tooth-stick, and let his spittle and the stick fall on the ascetic’s matted locks. Then he bathed his head, and his army did likewise.

When the King departed, the commander-in-chief came. And seeing the ascetic, he took the tooth-stick out of his locks and had him thoroughly washed. Then he asked, “What will become of the King?” “Sir, there is no evil thought in my heart, but the gods are angry, and on the seventh day from now his entire kingdom will be destroyed. You should flee with all speed and go elsewhere.” He was terribly alarmed and went and told the King. But the King refused to believe him. So he returned to his own house, and taking his wife and children with him, he fled to another kingdom.

The master Sarabhaṅga heard about this. He sent two youthful ascetics and had Kisavaccha brought to him in a litter through the air. The King fought the battle, and taking the rebels prisoners, he returned to the city. But on his return the gods caused it to rain from heaven. And when all the dead bodies had been washed away by the flood, there was a shower of heavenly flowers on the top of the clean white sand. A shower of small coins fell on the flowers. After them there was a shower of big coins. This was followed by a shower of heavenly ornaments.

The people were delighted. They began to pick up ornaments of gold, even fine gold. Then there rained a shower of all manner of blazing weapons. The people were cut up piece-meal. Next a shower of blistering embers fell on them, and over these fell huge blazing mountain peaks, followed by a shower of fine sand filling a space of sixty cubits. (A cubit is about .5 meters or 1.64 feet.) In this way a part of his realm sixty leagues (A league is about 556 meters or three miles) in extent was destroyed. Its destruction was blazed abroad throughout all India.

Then the lords of subordinate kingdoms within his realm, the three Kings, Kaliṅga, Aṭṭhaka, Bhīmaratha, thought, “Once upon a time in Benares, Kalābu, King of Kāsi, having mistreated the ascetic Khantivādī, was swallowed up in the earth. In the same way, Nāḷikīra had ascetics devoured by dogs, and Ajjuna of the thousand arms who mistreated Aṅgīrasa likewise perished. Now King Daṇḍaki, having mistreated Kisavaccha is destroyed, realm and all. We do not know where these four Kings were reborn. No one except our master Sarabhaṅga will be able to tell us. We will go and ask him.”

So the three Kings went forth with great pomp to ask this question. But even though they heard rumors that the others had gone, they did not really know it. Each one thought that he was traveling alone. Not far from Godhāvarī they all met. Dismounting from their chariots, they all three mounted on a single chariot and journeyed together to the banks of Godhāvarī.

At this moment Sakka was sitting on his throne of yellow marble. He considered seven questions and said to himself, “Except Sarabhaṅga, the master, there is no one else in this world or the god-world that can answer these questions. I will ask him these questions. These three Kings have gone to the banks of Godhāvarī to question Sarabhaṅga, the master. I will also ask him about the questions they have.” And, accompanied by deities from two of the god-worlds, he descended from heaven.

On that very day (the ascetic) Kisavaccha died. To celebrate him, innumerable bands of ascetics, who lived in four different places, raised a pile of sandalwood and cremated his body. A shower of celestial flowers fell half a league around the place of his cremation. The Great Being, after seeing to the depositing of his remains, entered the hermitage. And attended by these bands of ascetics, he sat down. When the Kings arrived on the banks of the river, there was a sound of martial music. When he heard it, the Great Being addressed the ascetic Anusissa and said, “Let us go and find out what this music means.” And taking a bowl of drinking-water, he went there. Seeing these Kings, he uttered this first stanza in the form of a question:

With jewels and gallantly arrayed,

All clad with jewel-hilted blade,

Halt you, great chiefs, and straight declare

What name ‘midst world of men you bear?

Hearing his words, they dismounted from the chariot and stood saluting him. Among them King Aṭṭhaka began to speak, uttering the second stanza:

Bhīmaratha, Kaliṇga famed,

And Aṭṭhaka—we are so named—

To look on saints of life austere

And question them, have we come here.

Then the ascetic said to them, “Well, sire, you have reached the place where you want to be. After bathing, rest. Then enter the hermitage, pay your respects to the band of ascetics, and ask your question to the master.” Having had this friendly conversation with them, he tossed the jar of water (a.k.a. a “good omen”), and wiping up the drops that fell, he looked up to the sky and saw Sakka, the lord of heaven. He was surrounded by a company of gods. And descending from heaven, he mounted the back of Erāvaṇa (Indra’s elephant). And speaking with Sakka, the ascetic repeated the third stanza:

You in mid-heaven are fixed on high

Like full-orbed moon that gilds the sky,

I ask you, mighty spirit, say

Why are you here on Earth, I pray.

On hearing this, Sakka repeated the fourth stanza:

Sujampati in heaven proclaimed

As Maghavā on Earth is named,

This king of gods today comes here

To see these saints of life austere.

Then Anusissa said to him: “Well, sire, follow us.” He took the drinking-vessel and entered the hermitage. And after putting away the jar of water, he announced to the Great Being that the three Kings and the lord of heaven had arrived to ask him certain questions. Surrounded by a band of ascetics, Sarabhaṅga sat in a large, wide enclosed space. The three Kings entered. And saluting the band of ascetics, they sat down on one side. Sakka descended from the sky and he approached the ascetics. He saluted them with folded hands. And singing their praises, repeated the fifth stanza:

Figure: Sakka and the three Kings enter the ascetic’s hut.

Wide known to fame this saintly band,

With mighty powers at their command,

I gladly bid you hail, in worth

You far surpass the best on Earth.

In this way Sakka salute the band of ascetics. And guarding against the six faults in sitting, he sat apart. Then Anusissa, seeing him seated to leeward of the ascetics, spoke the sixth stanza:

The person of an aged saint

Is rank, the very air to taint.

Great Sakka, beat a quick retreat

From saintly odors, none too sweet.

On hearing this, Sakka repeated another stanza:

Though aged saints offend the nose

And taint the sweetest air that blows,

Pretty flowers’ fragrant wreath above

This odor of the saints we love,

In gods it may no loathing move.

And having so spoken, he added, “Reverend Anusissa, I have made a great effort to come here and ask a question. Grant me permission to do so.” And on hearing Sakka’s words, Anusissa rose from his seat. He granted him permission, repeating a couple of stanzas to the company of ascetics:

Famed Maghavā, Sujampati

—Almsgiver, lord of sprites is he—

Queller of demons, heavenly king,

Craves leave to put his questioning.

Who of the sages that are here

Will make their subtle questions clear

For three who over men hold sway,

And Sakka whom the gods obey?

On hearing this, the company of ascetics said, “Reverend Anusissa, except our teacher Sarabhaṅga, who else is competent to answer these questions?” And so saying, they repeated a stanza:

‘Tis Sarabhaṅga, sage and saint,

So chaste and free from lustful taint,

The teacher’s son, well disciplined,

Solution of their doubts will find.

And so saying, the company of ascetics addressed Anusissa. “Sir, salute the teacher in the name of the company of saints and find an opportunity to tell him the question proposed by Sakka.” He readily assented and, finding his opportunity, he repeated another stanza:

The holy men, Kondañña, pray

That you would clear their doubts away.

This burden lies, as mortals hold,

On men in years and wisdom old.

(“Kondañña “is the family name of Sarabhaṅga.)

The Great Being gave his consent, repeated the following stanza:

I give you leave to ask whate’er

You most at heart would hope to hear,

I know both this world and the next,

No question leaves my mind perplexed.

Sakka, having thus obtained his permission, asked the question that he had prepared:

The Master, to make the matter clear, said:

Sakka, to cities bountiful, that sees the Truth of things,

To learn what he would hope to know, began his questionings.

What is it one may slay outright and never more repent?

What is it one may throw away, with all good men’s consent

From whom should one put up with speech, however harsh it be?

This is the thing that I would have Kondañña tell to me.

Then explaining the question, he said:

Anger is what a man may slay and never more repent,

Hypocrisy he throws away with all good men’s consent.

From all he should put up with speech, however harsh it be,

This form of patience, wise men say, is highest in degree.

Rude speech from two one might with patience hear,

From one’s superior, or from a peer,

But how to bear from meaner folk rude speech

Is what I hope Kondañña would now teach.

Rude speech from betters one may take through fear

Or, to avoid a quarrel, from a peer,

But from the mean to put up with rude speech

Is perfect patience, as the sages teach.

Verses such as these one must understand to be connected in the way of question and answer.

When he had spoken, Sakka said to the Great Being, “Holy sir, in the first instance you said, “Put up with harsh speech from all. This, men say, is the highest form of patience,” But now you say, “Put up with the speech of an inferior. This, men say, is the highest form of patience.” This latter saying does not agree with your former one.”

Then the Great Being said to him, “Sakka, this last utterance of mine is in respect of one who puts up with harsh speech because he knows the speaker to be his inferior. But what I said first was because one cannot by merely looking at people know for certain their condition, whether superior to oneself or not.” And to make it clear how difficult it is to distinguish the condition of persons by simply looking at them—whether inferior or not—except by means of close interaction, he spoke this stanza:

How hard it is to judge a man that’s polished in exterior

Be he one’s better, equal or, it may be, one’s inferior.

The best of men pass through the world often in meanest form disguised,

So then bear with rough speech from all, if you, my friend, be well advised.

On hearing this Sakka—full of faith—begged him, saying, “Holy sir, tell us the blessing to be found in patience.” And the Great Being repeated this stanza:

No royal force, however vast its might,

Can win so great advantage in a fight

As the good man by patience may secure

Strong patience is of fiercest feuds the cure.

When the Great Being had expounded the virtues of patience, the Kings thought, “Sakka asks his own question, but he will not give us an opportunity of asking ours.”

Seeing their wish, he laid aside the four questions he had prepared. And easing their doubts, he repeated this stanza:

Your words are grateful to my ear,

But one thing more I want to hear.

Tell us the fate of Daṇḍaki

And of his fellow wrong doers three,

Destined to suffer what rebirth

For harassing the saints on earth.

Then the Great Being, answering his question, repeated five stanzas:

Uprooted, realm and all, a while

Who Kisavaccha did defile,

O’erwhelmed with fiery embers, see,

In Kukkula lies Daṇḍaki.

Who made him sport of priest and saint

And preacher, free from wicked taint,

This Nāḷikīra trembling fell

Into the jaws of dogs in hell.

So Ajjuna, who slew outright

That holy, chaste, good man upright,

Aṅgīrasa, was headlong hurled

To tortures in a suffering world.

Who once a righteous saint did maim

—Preacher of Patience was his name—

Kalābu now does scorch in hell,

Midst anguish sore and terrible.

The man of wisdom that hears tell

Of tales like these or worse of hell,

Ne’er against priest or saint mistreats

And heaven by his right action greets.

(“Kukkala” is the hot embers of hell. “Aṇgīrasa” is also a hell realm.)

When the Great Being had pointed out the places in which the four Kings were reborn, the three Kings were freed from all doubt. Then Sakka asked his remaining four questions in this stanza:

Your words are grateful to my ear,

But one thing more I want to hear:

Who does the world as “moral” name,

And who does it as “wise” proclaim?

Who does the world for “pious” take,

And who does Fortune ne’er forsake?

Then in answering him the Great Being repeated four stanzas:

Who does in act and word shows self-restraint,

And e’en in thought is free from wicked taint,

Nor lies to serve his own base ends—the same

All men as “moral” evermore proclaim.

He who revolves deep questions in his mind

Yet perpetrates nothing cruel, unkind,

Prompt with good word in season to advise,

That man by all is rightly counted wise.

Who grateful is for kindness once received,

And sorrow’s need has carefully relieved,

Has proved himself a good and steadfast friend—

Him all men as a pious one commend.

The one with every gift at their command,

True, tender, free and bountiful of hand,

Heart-winning, gracious, smooth of tongue withal—

Fortune from such a one will never fall.

In this way the Great Being, as if he were causing the moon to rise in the sky, answer the four questions. Then followed other questions and their answers.

Your kindly words fall grateful on my ear,

But one thing further I want to hear,

Virtue, fair fortune, goodness, wisdom—say

Which of all these do men call best, I pray.

Wisdom good men declare is best by far,

E’en as the moon eclipses every star

Virtue, fair fortune, goodness, it is plain,

All duly follow in the wise man’s train.

Your kindly words fall grateful on my ear,

But one thing further I want to hear,

To gain this wisdom what is one to do,

What line of action or what course pursue?

Tell us what way the path of wisdom lies

And by what acts a mortal does grow wise?

With clever, old, and learned men consort,

Wisdom from them by questioning extort,

Their goodly counsels one should hear and prize,

For in this way a mortal man grows wise.

The sage regards the lure of things of sense

In view of sickness, pain, impermanence.

Midst- sorrows, lust, and terrors that appall,

Calm and unmoved the sage ignores them all.

He would conquer misdeeds, from passion free,

And cultivate a boundless charity.

To every living creature mercy show,

And, blameless soul, to world of Brahma go.

While the Great Being was still speaking of the defilements of sensual desires, these three Kings—together with their armies—abandoned the passion of sensual pleasure by means. And the Great Being, becoming aware of this, praised them, reciting this stanza:

Bhīmaratha by power of magic came

With you, O Aṭṭhaka, and one to fame

As King Kaliṅga known, and now all three,

Once slaves to sensuality, are free.

On hearing this, the mighty Kings sang the praises of the Great Being, reciting this stanza:

‘Tis so, you reader of men’s thoughts, all three

Of us from sensuality are free,

Grant us the boon for which we want to gain,

That to your happy state we may attain.

Then the Great Being granted them this favor, repeating another stanza:

I grant the boon that you would have of me,

The more that you from sensual vice are free.

So may you thrill with boundless joy to gain

That happy state to which you would attain.

On hearing this they signified assent, repeating this stanza:

We will do everything at your request,

Whate’er you in your wisdom deem the best.

So we will thrill with boundless joy to gain

That happy state to which we would attain.

Then the Great Being granted holy orders to their armies. And dismissing the band of ascetics, he repeated this stanza:

Due honor lo! to Kisavaccha came,

So now depart, you saints of goodly fame.

In ecstasy delighting calmly rest,

This joy of holiness is far the best.

The saints, assenting to his words by bowing to him, flew up into the air and departed to their own places. Sakka rose from his seat. He raised his folded hands. And paying homage to the Great Being as though he were worshipping the sun, he departed with his company.

On seeing this, the Master repeated these stanzas:

Hearing these strains that Highest Truth did teach

Set forth by holy sage in goodly speech,

The glorious Beings to their heavenly home

Once more with joy and gratitude did come.

The holy sage’s strains strike on the ear

Pregnant with meaning and in accents clear.

Who gives good heed and concentrates his mind

Upon their special thought will surely find

The path to every stage of ecstasy,

And from the range of tyrant Death is free.

In this way the Master brought his teaching to a climax in Arhatship, saying, “Not now only, but in the past, also, there was a rain of flowers at the cremation of Moggallāna.” Then he taught the Four Noble Truths and identified the Birth: “Sālissara was Sāriputta, Meṇḍissara was Kassapa, Pabbata was Anuruddha, Devala was Kaccāyana, Anusissa was Ānanda, Kisavaccha was Kolita, and Sarabhaṅga was the Bodhisatta. In this way you are to understand the birth.”