Jataka 524

Saṃkhapāla Jātaka

The Story of Saṃkhapāla

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a powerful story about the diligence, patience and forbearance of the Bodhisatta, along with the equally extreme love and compassion of the ascetic Aḷāra, who was Sāriputta in a previous existence.

“Of a pretty presence.” The Master told this story while living at Jetavana. It is about the duties of the holy (uposatha) days. Now on this occasion the Master, expressing approval of certain lay folk who kept the holy days, said: “Wise men of old, giving up the great glory of the Nāga world, observed holy days.” And at their request, he told them this story from the past.

(A “Nāga” is a serpent spirit who can also take the form of a human. They are usually depicted as cobras.)

Once upon a time, the King of Magadha ruled in Rājagaha. At that time the Bodhisatta was born as the son of this King’s chief consort. They gave him the name of Duyyodhana. When he came of age, he mastered the liberal arts at Takkasilā University, and then he returned home to see his father. His father installed him in the kingdom. The King then adopted the holy life and took up residence in the park.

The Bodhisatta went to visit his father three times a day. From this he received great profit and honor. However, because of this distraction, the King failed to perform even the preparatory rites that lead to mystic meditation (jhāna). He thought, “I am receiving great profit and honor. But if I live here, it will be impossible for me to destroy this lust of mine. Without saying a word to my son, I will leave.”

So not telling anyone, he departed. He passed beyond the borders of Magadha where he built a hut of leaves in the Mahiṃsaka kingdom. It was near Mount Candaka, in a bend of the river Kaṇṇapeṇṇā, where it issues out of the lake Saṃkhapāla. There he took up his residence. And performing the preparatory rites, he developed the faculty of mystic meditation and subsisted on whatever he could find.

A king of the Nāgas, Saṃkhapāla by name, came out of the Kaṇṇapeṇṇā river with a large company of snakes. From time to time, he would visit the ascetic who instructed the Nāga king in the Dharma.

Now the son was anxious to see his father, but he did not know where he had gone. He set out and discovered where his father was living. He left with a large retinue to see him. He halted a short distance off, accompanied by a few courtiers. Then he set out in the direction of the hermitage.

At this moment Saṃkhapāla sat listening to the Dharma with a large following. But when he saw the King approach, he rose up. And with a salutation to the sage, he departed. The King saluted his father, and after exchanging the usual courtesies, he asked, “Reverend sir, what king is this that has been to see you?” “Dear son, he is Saṃkhapāla, the Nāga king.” The son saw the great magnificence of the Nāga world, and he developed a longing it.

He stayed there for a few days, furnishing his father with a constant supply of food. Then he returned to his own city. There he had alms-halls erected at the four city gates, and because of his almsgiving, he created a stir throughout all India. And in his aspiration to be reborn in the Nāga world, he kept the moral law and observed the duty of the holy days. And at the end of his life, he was reborn in the Nāga world as king Saṃkhapāla.

In the course of time, he tired of this magnificence. From that day on he wanted to be born as a man. So he kept the holy days. But living as he did in the Nāga world, his observance of them was not successful, and his morals deteriorated. So he left the Nāga world, and not far from the river Kaṇṇapeṇṇā, he coiled himself around an anthill between the high road and a narrow path. There he resolved to keep the holy day and keep the moral law. He said, “Let those that want my skin or my skin and flesh, let them, I say, take it all.” And sacrificing himself by way of charity, he lay on the top of the anthill.

He stayed there on the fourteenth and fifteenth of the half-month, and on the first day of each fortnight he returned to the Nāga world. One day he lay there, having taken the vows of the moral law. A party of sixteen men who lived in a neighboring village, having a mind to eat flesh, roamed about in the forest with weapons in their hands. When they returned without finding anything, they saw him lying on the anthill. They thought, “Today we have not caught so much as a young lizard. We will kill and eat this snake king.” But they were afraid that because of his great size, even if they caught him, he would escape from them. They thought they would stab him with stakes as he lay there coiled up, and after disabling him, they could affect his capture.

So taking stakes in their hands, they drew near to him.

The Bodhisatta caused his body to become as big as a trough-shaped canoe. He looked very beautiful, like a jasmine wreath deposited on the ground. He had eyes like the fruit of the guñjá shrub and a head like a jayasumana (a red China rose) flower. At the sound of the footsteps of these sixteen men, he drew his head out from his coils. He opened his fiery eyes and saw them coming with stakes in their hands. He thought, “Today my desire will be fulfilled as I lie here. I will be firm in my resolution and give myself up to them as a sacrifice. And when they strike me with their javelins and cover me with wounds, I will not open my eyes and regard them with anger.” And resolving not to break the moral law, he tucked his head into his hood and lay down.

Figure: The Bodhisatta endures a spear.

They went up to him and seized him by the tail, dragging him along the ground. They dropped him and wounded him in eight different places with sharp stakes. They stabbed him with black bamboo sticks, thorns and all, into his open wounds. Then they proceeded on their way, binding him with strings in the eight wounds.

From the moment he was wounded, the Great Being never opened his eyes or regarded the men with anger. As he was being dragged along by means of the eight sticks, his head hung down and struck the ground. When they saw that his head was drooping, they laid him down on the high road and pierced his nostrils with a slender stake. They held his head up and inserted a cord, and after fastening it at the end, they once more raised his head up and set out on their way.

At this moment a landowner named Aḷāra, who lived in the city of Mithila in the kingdom of Videha, was sitting in a comfortable carriage. He was traveling with 500 wagons. And seeing these lewd fellows on their way with the Bodhisatta, he gave all 16 of them a handful of golden coins along with an ox. In addition, he gave each of them outer and inner garments, and he gave ornaments to their wives to wear. In this way, he got them to release him.

The Bodhisatta returned to the Nāga palace, and without any delay, he left with a great retinue. He approached Aḷāra, and after singing the praises of the Nāga palace, he took him and returned there. Then he bestowed great honor on him together with 300 Nāga maidens. He satisfied him with heavenly delights. Aḷāra lived for a whole year in the Nāga palace in the enjoyment of heavenly pleasures. Then he said to the Nāga king, “My friend, I wish to become an ascetic.” So he took everything needed for the ascetic life with him and left the home of the Nāgas for the Himalaya region. There he took holy orders, and he lived there for a long time.

By and by he went on a pilgrimage. He went to Benares where he took up his residence in the King’s park. On the next day, he entered the city for alms and made his way to the door of the King’s house. When he saw him, the King of Benares was so charmed with his deportment that he called him into his presence. He seated him on a special seat and served him with a variety of dainty food. Then—seated on a low seat—the King saluted him. And talking with him, he said the first stanza:

Of comely presence and gracious manner,

You are of noble rank, I gather.

Why then renounce earth’s joys and worldly gear

To adopt the hermit’s robe and rule severe?

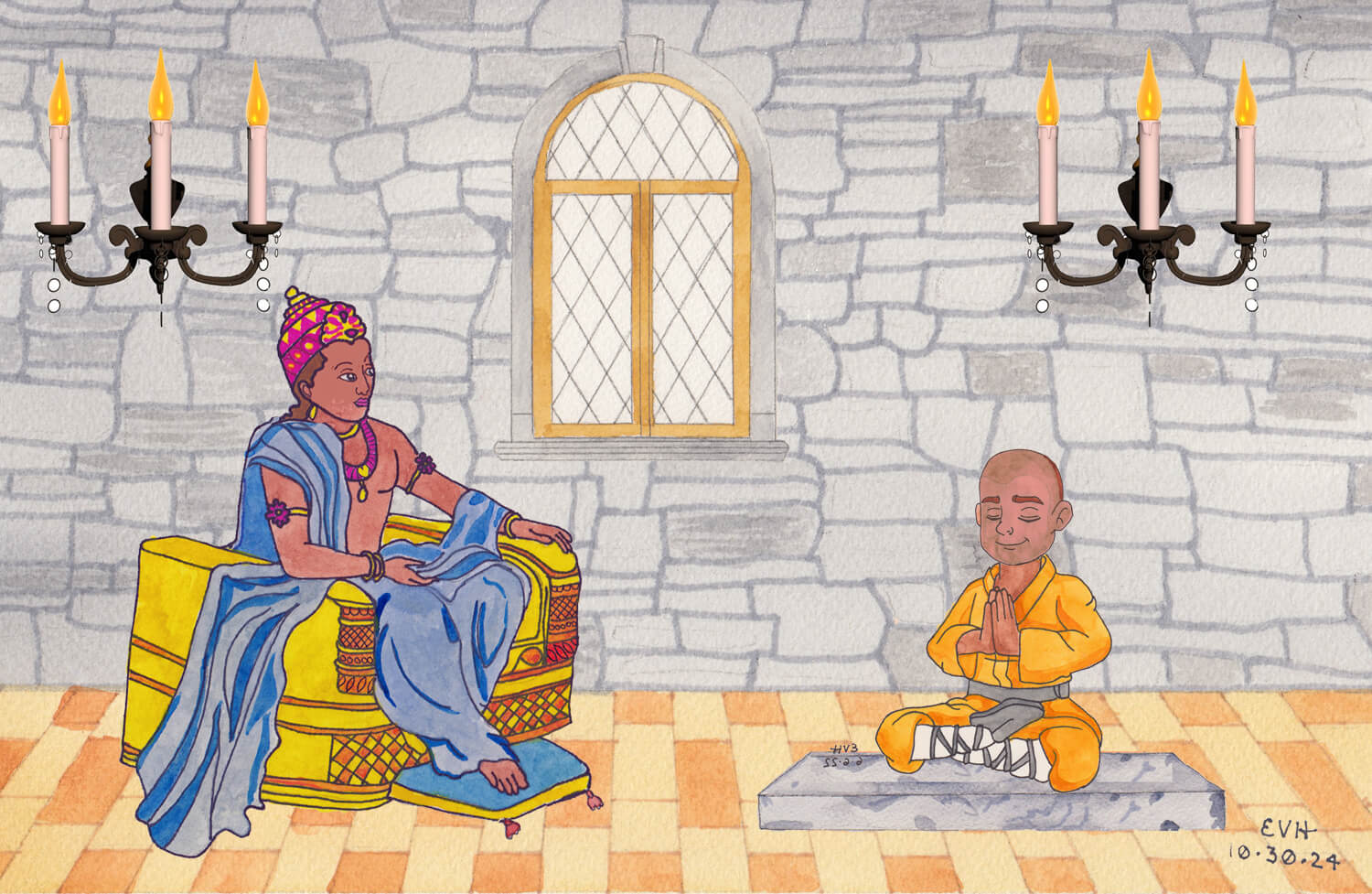

Figure: The King receives the blessings of the ascetic.

In what follows, the connection of the stanzas is to be understood in the way of alternate speeches by the ascetic and the King.

O lord of men, I well remembering

The abode of that almighty Nāga king,

Saw the rich fruit that springs from holiness,

And straight believing donned the holy dress.

Not fear or lust or hate itself may make

A holy man the words of truth forsake,

Tell me the thing that I do want to know,

And faith and peace within my heart will grow.

O King, on trading venture was I bound.

When these lewd wretches in my path were found,

A full-grown snake in captive chains was led,

And home in triumph joyously they sped.

As I came up with them, O King, I cried,

—Amazed I was and greatly terrified—

“Where are you dragging, sirs, this monster grim,

And what, lewd fellows, will you do with him?”

“This full-grown snake that you see bundled thus

With its huge frame will furnish food to us.

Then this, Aḷāra, you could hardly wish

To taste a better or more savory dish.”

“So to our home we’ll fly and quickly dice

Each with his knife cut off a dainty slice

And gladly eat his flesh, for, as you know,

Snakes ever find in us a deadly foe.”

“If this huge snake, late captured in the wood,

Is being dragged along to serve as food,

To each an ox I offer, one apiece,

Should you this serpent from his chains release.”

“Beef has for us a pleasant sound, I vow,

On snake’s flesh we have fed full often now,

Your bidding, O Aḷāra, we will do,

Henceforth let friendship reign between us two.”

Then they released him from the cord that passed

Right through his nose and knotted held him fast,

The serpent king set free from bondage vile

Turned him towards the east, then paused awhile.

And facing still the east, prepared to fly,

Looked back upon me with a tearful eye,

While I pursued him upon his way

Stretched forth clasped hands, as one about to pray.

“Speed you, my friend, like one in haste that goes,

Lest once again you fall among such foes,

Of such like ruffians shun the very sight,

Or you may suffer to your own despite.”

Then to a charming limpid pool he sped

—Canes and rose apples both its banks o’erspread—

Right glad at heart, no further fear he knew,

But plunged in liquid depths was lost to view.

No sooner vanished had the snake, then he

Revealed full clearly his divinity.

In kindly acts he played a dutiful part,

And with his grateful speeches touched my heart.

“You dearer than my parents did restore

My life, true friend e’en to your inmost core,

Through you my former bliss has been regained,

Then come, Aḷāra, see where I once reigned,

A palace stored with food, like Indra’s town

Masakkasāra, place of high renown.”

After he had spoken these words, the serpent king still further sang the praises of his dwelling place, and he repeated a couple of stanzas:

What charming spots in my domain are seen,

Soft to the tread and clothed in evergreen!

Not dust or gravel in our path we find,

And there do happy souls leave grief behind.

Midst level courts that sapphire walls surround

Fair mango groves on every side abound,

Whereon ripe clusters of rich fruit appear

Through all the changing seasons of the year.

Amidst these groves a fabric wrought of gold

And fixed with silver bolts you may behold,

A dwelling bright in splendor, to defy

The lightning flash that gleams across the sky.

Fashioned with gems and gold, divinely fair,

And decked with paintings manifold and rare,

‘Tis thronged with nymphs magnificently dressed,

All wearing golden chains upon their breast.

Then in hot haste did Saṃkhapāla climb

The terraced height, on which in power sublime

Uplifted on a thousand piers was seen

The palace of his wedded wife and queen.

Quickly and soon one of that maiden band

Bearing a precious jewel in her hand,

A turquoise rare with magic power replete,

And all unbidden offered me a seat.

The snake then grasped my arm and led me where

There stood a noble and right royal chair.

“Pray, let your Honor sit here by my side,

As parent dear to me are you,” he cried.

A second nymph then quick at his command

Came with a bowl of water in her hand,

And bathed my feet, kind service tendering

As did the queen for her dear lord the king.

Another maiden in that paradise

Served in a golden dish some curried rice,

Flavored with many a sauce, that gladly might

With dainty cravings tempt the appetite.

With strains of music then—for such they knew

Was their lord’s wish—they wanted to subdue

My will, nor did the king himself e’er fail

My soul with heavenly longings to assail.

Drawing near to me he repeated another stanza:

Three hundred wives, Aḷāra, here have I,

Slim-waisted all, in beauty they defy

The lotus flower. Behold, they only live

To do your will. Accept the boon I give.

Aḷāra said:

One year with heavenly pleasures I was blessed

When to the king this question I addressed,

“How, Nāga, is this palace fair your home,

And how to be your portion did it come?

Was this fair place by accident attained,

Built by yourself, or gift from angels gained?

I ask you, Nāga king, the truth to tell,

How did you come in this fair place to dwell?”

Then followed stanzas uttered by Aḷāra and the Nāga king alternately:

‘Twas by no chance or natural law attained,

Not built by me, no boon from angels gained,

But to my own good actions, you must know,

And to my merits these fair halls I owe.

What holy vow, what life so chaste and pure

What store of merit could such bliss secure?

Tell me, O serpent king, for I would deign

To know how this fair mansion you could gain.

I once was King of Magadha, my name

Duyyodhana, a prince of mighty fame,

I held my life as vile and insecure,

Without all power in ripeness to mature.

Meat and drink I religiously supplied,

And bestowed alms on all, both far and wide,

My house was like an inn, where all that came,

Sages and saints refreshed their weary frame.

Bound by such vows, such was the life I passed,

And such the store of merit I amassed,

Whereby this mansion was at length attained,

And food and drink in ample measure gained.

This life, however bright for many a day

With dance and song, did finally fall away,

Weak creatures harry you for all your might

And feeble beings put the strong to flight.

Why, armed to the teeth in such unequal fray,

To those vile beggars should you fall a prey?

By what o’ermastering dread were you undone?

Where had the virus of your poison gone?

Why, armed to the teeth and powerful you were such,

From such poor creatures did you suffer much?

By no o’ermastering dread was I undone,

Nor could my powers be crushed by anyone.

The worth of goodness is by all confessed,

Its bounds, like the seashore, are ne’er transgressed.

Two times each moon I kept a holy day,

‘Twas then, Aḷāra, that there crossed my way

Twice eight lewd fellows, bearing in their hand

A rope and knotted noose of finest strand.

The ruffians pierced my nose, and through the slit

Passing the cord, dragged me along by it.

Such pain I had to bear—ah! cruel fate—

For holding holy days inviolate.

Seeing in that lone path, stretched at full length,

A thing of beauty and enormous strength,

“Why, wise and glorious one,” I cried, “do you

Take on yourself this strict ascetic view?”

Neither for child nor wealth is my desire

Nor yet to length of days do I aspire.

But midst the world of men I gladly thrive,

And to this end heroically strive.

With hair and beard well-trimmed, your sturdy frame

Adorned with gorgeous robes, an eye of flame,

Bathed in red sandal oil you seem to shine

Afar, e’en as some minstrel king divine.

With heavenly gifts miraculously blessed

And of whate’er your heart may crave possessed,

I ask you, serpent king, the truth to tell,

Why do you in man’s world prefer to dwell?

Nowhere but in the world of men, I glean,

May purity and self-restraint be seen.

If only once midst men I draw my breath,

I’ll put an end to further birth and death.

Ever supplied with bountiful good cheer,

With you, O king, I’ve traveled for a year,

Now I must say farewell and go away,

Absent from home I can no longer stay.

My wife and children and our dependent band

Are ever trained to wait at your command.

No one, I trust, has offered you a slight

For you are dear, to my sight.

Kind parents’ presence fills a home with joy,

Yet more than they some fondly cherished boy.

But greatest bliss of all I have found here,

For you, O king, has ever held me dear.

I have a jewel rare with blood-red spot,

That brings great wealth to such as have it not.

Take it and go to your own home, and when

You have grown rich, pray, send it back again.

Aḷāra, having spoken these words proceeded as follows: “Then, O sire, I addressed the serpent king and said, ‘I have no need of riches, sir, but I am anxious to take the holy vows.’ And having begged for the requisites for the ascetic life, I left the Nāga palace together with the King. And after sending him back, I entered the Himalaya country and took the holy vows.” And after these words he delivered a holy discourse to the King of Benares and repeated yet another couple of stanzas:

Desires of man are transient, nor can they

The higher law of ripening change obey.

Seeing what woes from wicked passion spring,

Faith led me on to be ordained, O King.

Men fall like fruit, to perish straight away,

All bodies, young and old alike, decay.

In holy orders only I find rest,

The true and universal is the best.

On hearing this the King repeated another stanza:

The wise and learned, such as meditate

On mighty themes, we all should cultivate.

Hearkening, Aḷāra, to the snake and you,

Lo! I perform all deeds of pure virtue.

Then the ascetic, using his strength, uttered a concluding stanza:

The wise and learned, such as meditate

On mighty themes, we all should cultivate.

Hearkening, O monarch, to the snake and me,

Do you perform all deeds of piety.

In this way he gave the King holy instruction. And after living in the same spot for the four months of the rainy season, he again returned to the Himalaya. As long as he lived, he cultivated the four Perfect States (brahma vihārās) until he passed on to the Brahma heaven. For as long as he lived, Saṃkhapāla observed the holy days. And the King, after he spent a life in charity and other good works, was reborn according to his karma.

End of story in the present...