Jataka 528

Mahābodhi Jātaka

The Supreme Knowledge

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

One of the most interesting parts of this story is that it chronicles some of the competing doctrines of the Buddha’s time:

- Denial of the principle of cause and effect, a.k.a. karma.

- That the universe is controlled by an all-powerful God.

- That everything is preordained and predestined.

- That there is no continuation after death, that when we die, that is the end of our existence.

- Belief in the caste system and the importance of social status.

Not surprisingly, the Buddha is able to refute all these doctrines. The Buddha’s Dharma places supreme importance on the law of cause and effect—karma—and the supreme importance of ethical, moral, and virtuous behavior in determining our value and our happiness now and in the future.

“What mean, these things.” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about the Perfection of Wisdom. The incident will be found related in the Mahāummagga (Jātaka 546). Now on this occasion the Master said, “Not only now, but formerly also, the Tathāgata was wise and crushed all opponents.” And with these words, he told a story from the past.

Once upon a time in the reign of Brahmadatta, the Bodhisatta was born at Benares in the kingdom of Kāsi. He was born into the family of a north brahmin magnate who was worth eighty crores (one crore is worth 10 million rupees). They named him Young Bodhi. When he came of age, he was instructed in all learning at Takkasilā University. And when he returned home, he lived in the midst of household concerns.

By and by he renounced worldly desires, and he retired to the Himalaya region. There he took up the ascetic life of a wandering mendicant. He lived there for a long time living on roots and wild berries. At the rainy season, he came down from the Himalayas and went on his alms rounds. Gradually he approached Benares. There he took up his residence in the royal park.

On the following day as he was going on his alms round, he drew near the palace gate. The king was standing at his window, and he saw him. Being delighted with his serene demeanor, he brought him into his palace and seated him on the royal couch. After a little friendly talk, the king listened to an exposition of the Dharma. Then he offered him a variety of dainty food. The Great Being accepted the food, but he discerned, “Truly this king’s court is full of hatred and is full of enemies. Who, I wonder, will rid me of a fear that has sprung up in my mind?”

He saw a tawny hound—a favorite of the king’s—standing near him. He took a lump of food and made a show of wishing to give it to the dog. The king saw this and had the dog’s dish brought. Then he told him to take the food and give it to the dog. The Great Being did so and then finished his own meal.

The king gave his consent to an arrangement. He had a hut of leaves built for him in the royal park within the city, and, assigning all that an ascetic required, he let him live there. And two or three times every day the king went to pay his respects to him. At mealtimes the Great Being continued to sit on the royal couch and to share the royal food. And so twelve years passed.

Now the king had five councilors who advised him on his worldly and spiritual duties. One of them denied the existence of karma. Another believed everything was the act of a Supreme Being. A third professed the doctrine of previous actions. A fourth believed in annihilation at death. A fifth held the Kshatriya doctrine (the caste system). The one who denied karma taught the people that beings in this world were purified by rebirth. The one who believed in the action of a Supreme Being taught that the world was created by him. The one who believed in the consequences of previous acts taught that sorrow or joy that befalls man here is the result of some previous action (predestination). The believer in annihilation taught that no one passes into another world, but that this world is annihilated. He who professed the Kshatriya creed taught that one’s own interest is to be desired even at the cost of killing one’s parents.

These men were appointed to sit in judgment in the king’s court. And being greedy, they dispossessed the rightful owner of his property. One day a certain man, having been mistreated in a false action at law, saw the Great Being go into the palace for alms. He saluted him and poured his grievance into his ears. He said, “Holy sir, why do you, who take your meals in the king’s palace, regard with indifference the action of his lord justices who take bribes and ruin men? Just now these five councilors, taking a bribe at the hands of a man who brought a false action, have wrongfully dispossessed me of my property.”

The Great Being was moved by compassion for him. So, he went to the court and gave a righteous judgment that reinstated his property to him. The people consented loudly and applauded his action. The king heard the noise and asked what it meant. On being told what it was—when the Great Being had finished his meal—he took a seat beside him and asked, “Is it true, reverend sir, as they say, that you have decided a lawsuit?” “It is true, sire.” The king said, “It will be to the advantage of the people if you decide cases. From now on, you are to sit in judgment.” “Sire,” he replied, “we are ascetics. This is not our business.” “Sir, you ought to do it from compassion for the people. You need not judge the whole day, but when you come here from the park, go to the place of judgment at early dawn and decide four cases. Then return to the park, and after eating decide four more cases. In this way the people will benefit.”

After being repeatedly entreated, he agreed to it. From then on, he acted accordingly. Those who brought fraudulent actions found no further opportunity, and the councilors—not getting any bribes—were in a desperate plight. They thought, “Ever since this mendicant Bodhi began to sit in judgment, we get nothing at all.” And calling him the king’s enemy, they said, “Come, let us slander him to the king and bring about his death.”

So drawing near to the king they said, “Sire, the mendicant Bodhi wishes you harm.” The king did not believe them and said, “No, he is a good and learned man. He would not do this.” “Sire,” they replied, “all the citizens are under his influence. We are the only five people he cannot get under his thumb. If you do not believe us, when he next comes here, take note of his following.” The king agreed to do so.

Standing at his window, he waited for him to arrive. And seeing the crowd of suitors who followed Bodhi without his knowledge, the king thought they were his retinue. Because he had been prejudiced against him, he summoned his councilors and asked, “What are we to do?” “Have him arrested, sire,” they said. “Unless we see some gross offence on his part,” he said, “how are we to arrest him?” “Well, then diminish the honor that is usually paid to him. When he sees this falling off of respect, being a wise mendicant, he will leave of his own accord without saying a word to anyone.” The king fell in with this suggestion and gradually diminished the respect paid to him.

On the first day after this they seated him on a bare couch. He noticed it and at once knew that he had been slandered to the king. When he returned to the park, he thought he would leave that very day. But then he thought, “When I know for certain, I will depart,” and he did not leave. So on the next day when he was seated on the bare couch, they came with food prepared for the king and other food as well. They gave him a mixture of the two. On the third day they did not allow him to approach the dais. Instead, they placed him at the head of the stairs where they offered him mixed food. He took it, and retiring to the park, he ate his meal there. On the fourth day they placed him on the terrace below and gave him broth made of rice dust. This, too, he took to the park where he ate his meal.

The king said, “Though the honors paid to him have diminished, Great Bodhi, the mendicant, does not go away. What are we to do?” “Sire,” they said, “it is not for alms he comes here. He is seeking sovereignty. If he were coming merely for alms, he would have run away the very first day that he was slighted.” “What then are we to do?” “Have him executed tomorrow, sire.” He said, “It is well.” So he gave swords to these very men, and he said, “Tomorrow, when he comes and stands inside the door, cut off his head and make mincemeat of him. And without saying a word to anyone, throw his body on a dunghill. Then take a bath and return here.”

They readily agreed and said, “Tomorrow we will come and do so.” They arranged matters with one another and departed to their homes. The king, too, after his evening meal, lay down on the royal couch. He began to recall the virtues of the Great Being. Then immediately sorrow fell upon him. Sweat poured from his body, and getting no comfort in his bed, he rolled about from side to side.

Now his chief queen lay beside him, but he did not exchange a single word with her. So she asked him, “How is it, sire, that you do not say a word to me? Have I in any way offended you?” “No, lady,” he said, “but they tell me that the mendicant Bodhi has become an enemy of ours. I have ordered five of my councilors to execute him tomorrow. After killing him, they will cut him in pieces and cast his body onto a dunghill. But for twelve years he has taught us many a truth. No single offence has ever been seen by me in him before. But at the instigation of others, I have ordered him to be put to death. This is why I grieve.” Then she comforted him, saying, “If, sire, he is your enemy, why do you grieve at killing him? Your own safety must be attended to, even if the enemy you slay is your own son. Do not take it to heart.” He was reassured by her words and fell asleep.

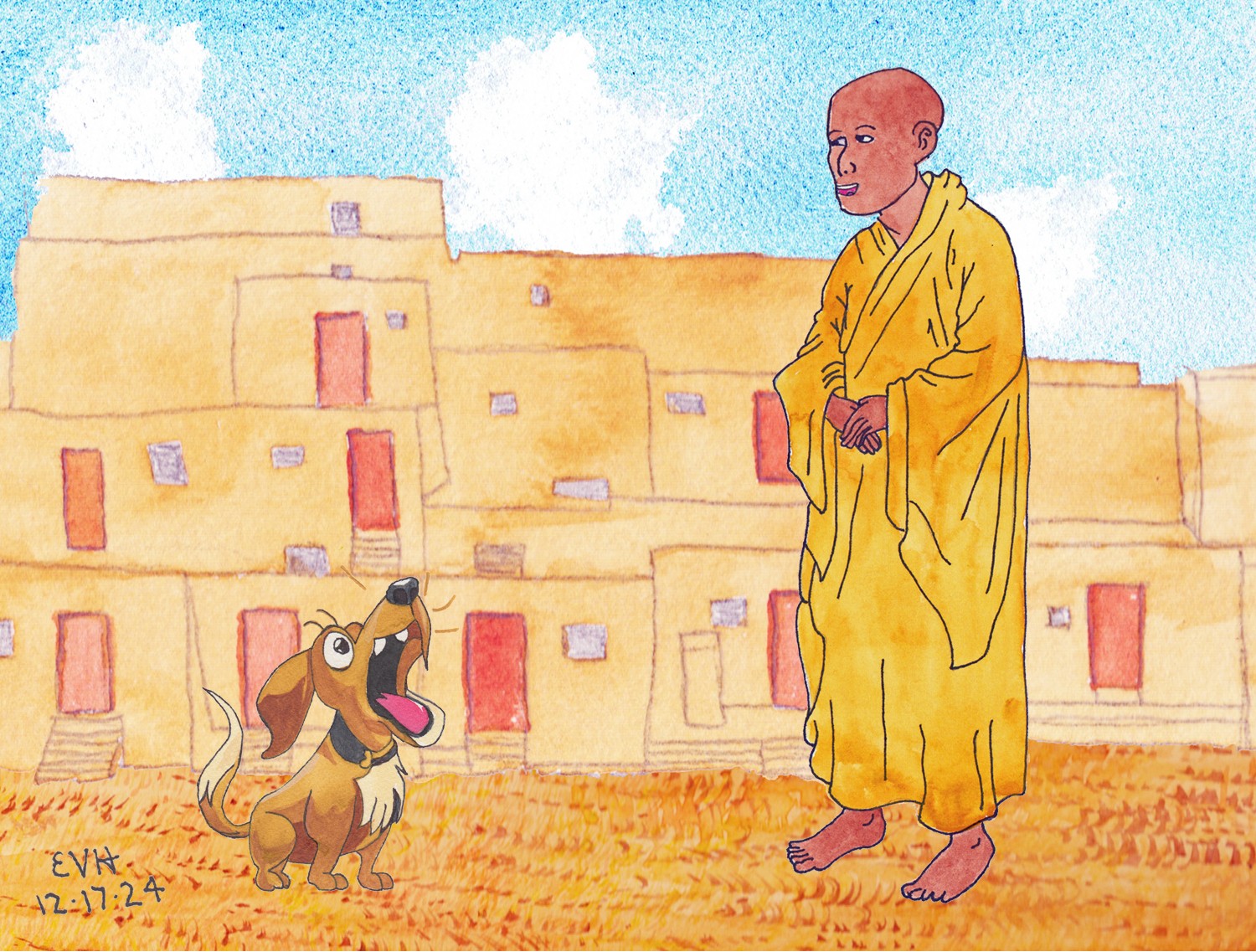

At that moment the well-bred tawny hound heard their talk. He thought, “Tomorrow I must save this man’s life by my own power.” So early next morning, the dog went down from the terrace. He went to the big door where he lay with his head on the threshold. There he watched the road by which the Great Being came.

Figure: The hound warns the Bodhisatta.

Those councilors came early in the morning with swords in their hands. They took their stand inside the door. And Bodhi—duly observing the time—came from the park and approached the palace door. But the hound saw him. He opened his mouth and showed his four big teeth. He thought, “Why, holy sir, do you not seek your alms elsewhere in India? Our king has posted five councilors armed with swords inside the door to kill you. Do not come accepting death as your fate but be off with all speed.” Then he gave a loud bark. Because he understood the meaning of all sounds, Bodhi understood the situation and returned to the park. He gathered everything that was required for his journey. But the king stood at his window, and when he saw he was not coming, he thought, “If this man is my enemy, he will return to the park and gather all his forces and will be prepared for action. But otherwise, he will certainly take all that he requires and go away. I will find out what he is about.” And going to the park, he found the Great Being coming out of his hut of leaves. He had all his requisites at the end of his cloister walk, ready to start. The king saluted him as he stood on one side, and he uttered the first stanza:

What mean these things, umbrella, shoes, skin-robe and staff in hand?

What of this cloak and bowl and hook? I would soon understand

Why in hot haste would you depart and to what far-off land?

On hearing this the Great Being thought, “I suppose he does not understand what he has done. I will let him know.” And he repeated two stanzas:

These twelve long years I’ve lived, O king, within your royal park,

And never once before today this hound was known to bark.

Today he shows his teeth so white, defiant now and proud,

And hearing what you told the queen, to warn me, bays aloud.

Then the king acknowledged his wickedness, and asking to be forgiven, he repeated the fourth stanza:

The misdeed was mine, holy sir, my purpose was to slay,

But now I favor you once more and please would have you stay.

Hearing this the Great Being said, “Truly, sire, wise men do not live with one who without having seen a thing with his own eyes follows the lead of others.” And so saying, he exposed his misconduct and said:

My food of old was pure and white, next mixed it was in hue,

Now it is brown as brown can be, ‘tis time that I withdrew.

First on the dais, then upstairs and last below I dine,

Before I’m thrust out neck and crop, my place I will resign.

Affect you not a faithless friend, like a dry well is he

However deep one digs it out, the stream will muddy be.

A faithful friend may cultivate, a faithless one eschew,

As one athirst hastes to a pool, a faithful friend pursue.

Cling to the friend that clings to you, his love with love requite,

One who forsakes a faithful friend is deemed a sorry blight.

Who clings not to a steadfast friend, or love requites with love,

Vilest of men is he, nor ranks the monkey tribe above.

To meet too often is as bad as not to meet at all,

To ask a boon a whit too soon—this too makes love to pall.

Visit a friend but not too oft, nor yet prolong your stay,

At the right moment favors beg, so love will ne’er decay.

Who stays too long find oftentimes that friend is changed to foe,

So now I lose your friendship, I will take my leave and go.

The king said:

Though I with folded hands implore, you will not lend an ear,

You have no word for us to whom your service would be dear.

I crave one favor, come again and pay a visit here.

The Bodhisatta said:

If nothing comes to snap our life, O king, if you and I

Still live, O fosterer of your realm, perhaps I’ll away fly,

And we may see each other yet, as days and nights go by.

In this way the Great Being preached the truth to the king, saying, “Be vigilant, O sire.” And leaving the park, after going on alms round in a place of his own choosing, he left Benares.

By degrees he reached a place in the Himalayas. After living some time there, he descended from the hills. He settled in a forest near a frontier village. As soon as he had left, those councilors once more sat in judgment robbing the people. The councilors thought, “Should Great Bodhi, the mendicant, return, we will lose our livelihood. What are we to do to prevent him from coming back?” Then this occurred to them: “People like that cannot leave any object to which they are attached. What can the object be here to which he is attached?” Then feeling sure it must be the king’s chief consort, they thought, “This is the reason why he would return here. We will put her to death.”

So, they repeated this to the king, saying, “Sire, today a certain report is circulating in the city.” “What report?” he said. “Great Bodhi the mendicant and the queen send messages back and forth to each other.” “With what purpose?” “His message to the queen, is this: ‘Will you be able to put the king to death and to grant me the white umbrella?’ Her message to him is, ‘The king’s death, truly, is my aim. Come quickly.’” (The white umbrella is the symbol of royal authority.)

They repeated this until the king believed it. He asked, “What is to be done?” They answered, “We must put the queen to death.” And without investigating the truth of the matter, he said, “Well, then, put her to death. Then cut up her body piecemeal and throw it on the dunghill.”

They did so. The news of her death was broadcast throughout the city. Then her four sons said, “Even thought she was innocent, our mother was put to death by this man.” The sons became the king’s enemies. The king was greatly terrified. In due course the Great Being heard what had happened. He thought, “Except for me there is no one who can pacify these princes and convince them to forgive their father. I will save the king’s life and deliver these princes from their evil purpose.”

(Killing a parent is a particularly egregious karmic offense.)

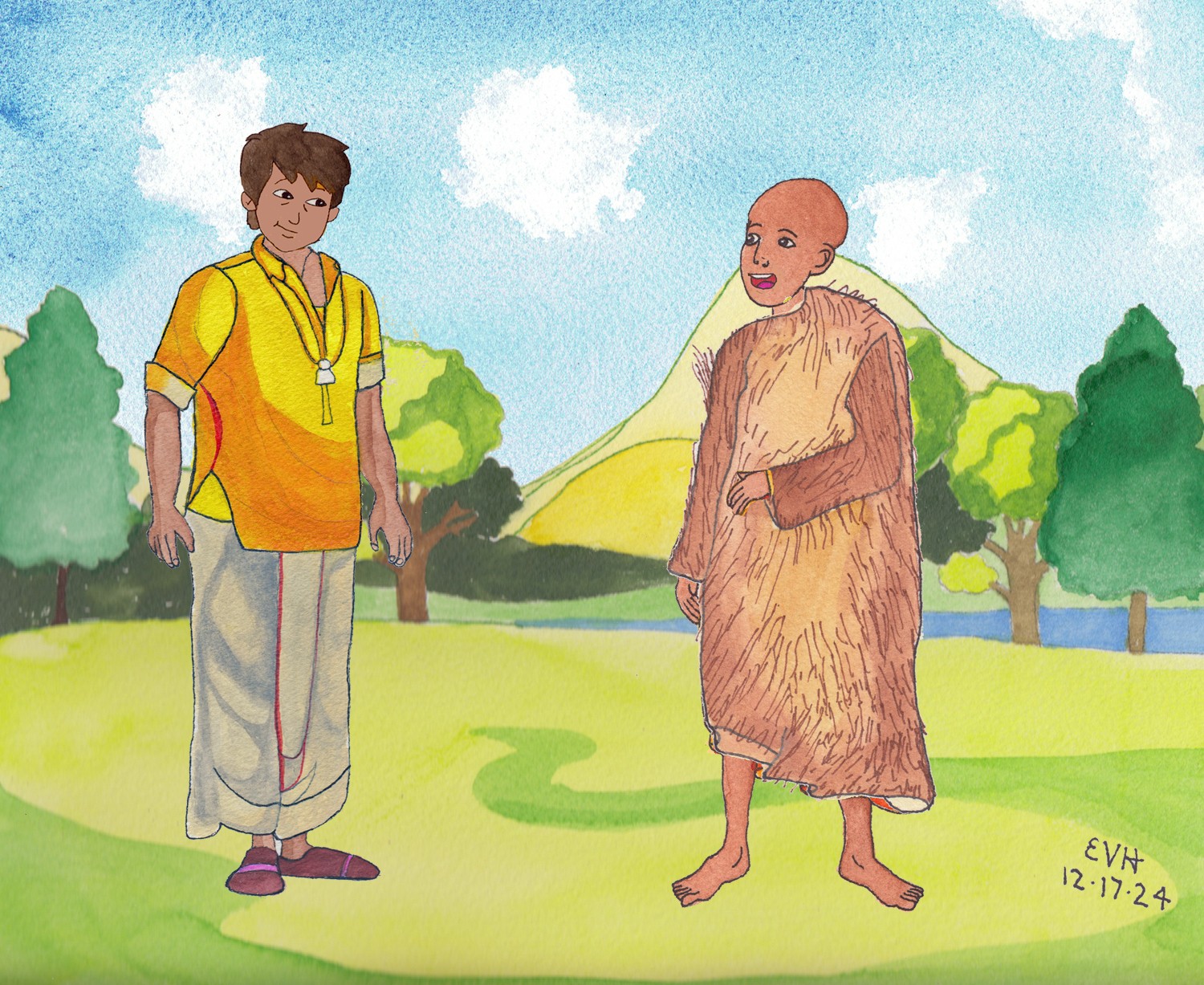

On the next day, he entered a frontier village. After eating the flesh of a monkey given to him by the inhabitants, he begged for its skin which he had dried in his hermit’s hut until it had lost its smell. (Except for the special dhutanga rules, vegetarianism is not required in the Dharma. Mendicants are supposed to receive all that is freely offered, even if that means meat.) Then he made it into an inner and outer robe which he laid on his shoulder. Why did he do this? It was so that he could say, “It is very helpful to me.” He took the skin with him and gradually made his way to Benares. He drew near to the young princes and said to them, “To murder one’s own father is a terrible thing. You must not do this. No mortal is exempt from decay and death. I have come here to appease you. When I send a message, come to me.” After having persuaded the youths, he entered the park in the city where he sat down on a stone slab, spreading the monkey-skin over it.

When the keeper of the park saw this, he went in haste to tell the king. The king on hearing it was filled with joy. He took the councilors with him, then he went and saluted the Great Being. And sitting down, he began to talk pleasantly with him. The Great Being—without exchanging any friendly greeting—went on stroking his monkey-skin. The king said, “Sir, without acknowledging me you continue to rub your monkey-skin. Is this more helpful to you than I am?” “Yes, sire. This monkey is of the greatest service to me. I travelled about sitting on its back. It carried my water-pot for me. It swept out my hut. It performed various duties for me. Through its innocence, I ate its flesh. Then I had its skin dried. I spread it out and sit and lie on it. So, it is very useful to me.”

In this way, to refute these heretics, he attributed the acts of a monkey to the monkey-skin. And with this purpose, he spoke as he did. From his having formerly dressed in its skin, he said, “I travelled about sitting on its back.” From placing it on his shoulder and carrying his drinking vessel, he said, “It carried my drinking vessel.” From having swept the ground with the skin, he said, “It sweeps out my hut.” When he lies down, his back is touched by this skin, and when he steps upon it, it touches his feet. Thus he said, “It performed various duties for me.” When he was hungry, because he took and ate its flesh, he said, “Being such an innocent creature, I ate its flesh.”

On hearing this the councilors thought, “This man is guilty of murder. Consider, the act of this ascetic. He says he killed a monkey, ate its flesh, and went about with its skin.” They clapped their hands and ridiculed him. When the Great Being saw them do this, he said, “These fellows do not know that I have come with this skin to refute their heresies. I will not tell them.” Addressing the one that denied karma, he asked, “Why, sir, do you blame me?” “Because you have been guilty of an act of treachery to a friend and of murder.” Then the Great Being said, “If one should believe in you and in your doctrine and act accordingly, what evil has been done?” And refuting his heresy he said:

If this your creed, “All acts of men, or good or base,

From natural causes spring, I hold, in every case,”

Where in unconditioned acts can misdeed find place?

If such the creed you hold and this be doctrine true,

Then was my action right when I that monkey slew.

Could you but only see how wicked is your creed,

You would no longer then with reason blame my deed.

In this way the Great Being rebuked him and reduce him to silence.

Figure: The Bodhisatta refutes the doctrine of the councilor.

The king was annoyed at the rebuke before the assembly. He collapsed and sat down.

Then the Great Being addressed the one who believed that everything is brought about by a Supreme Being. He said, “Why, sir, do you blame me, if you really believe that everything is the creation of a Supreme Being?” And he repeated this verse.

If there exists some Lord all powerful to fulfill

In every creature bliss or woe, and action good or ill,

That Lord is stained with misdeed, man only works his will.

If such the creed you hold and this be doctrine true,

Then was my action right when I that monkey slew.

Could you but only see how wicked is your creed,

You would no longer then with reason blame my deed.

In this way, like one knocking down a mango with a club, he refuted the man who believed in the action of some Supreme Being.

Then he addressed the believer in all things having happened before, saying, “Why, sir, do you blame me if you believe in the truth of the doctrine that everything has happened before?” And he repeated this verse:

From former action still both bliss and woe begin,

This monkey pays his debt, to wit, his former sin,

Each act’s a debt discharged. Where then does guilt come in?

If such the creed you hold and this be doctrine true,

Then was my action right when I that monkey slew.

Could you but only see how wicked is your creed,

You would no longer then with reason blame my deed.

Having thus refuted the heresy of this man too, he turned to the believer in annihilation. He said, “You, sir, maintain that there is no reward, believing that all mortals suffer annihilation here, and that no one goes to a future world. Why then do you blame me?” And rebuking him he said:

Each living creature’s form four elements compose,

To these component parts dissolved each body goes.

The dead exist no more, the living still live on,

Should this world be destroyed, both wise and fools are gone,

Amidst a ruined world guilt does defile none.

If such the creed you hold and this be doctrine true,

Then was my action right when I that monkey slew.

Could you but only see how wicked is your creed,

You would no longer then with reason blame my deed.

In this way he refuted the heresy of this one, too.

Then he addressed the one who held the Kshatriya doctrine. He said, “You, sir, maintain that a man must serve his own interests, even if he kills his own father and mother. Why, if you go about professing this belief, do you blame me?” And he repeated this verse:

The Kshatriyas say, poor simple fools that think themselves so wise,

A man may kill his parents, if occasion justifies,

Or elder brother, children, wife, should need of it arise.

In this way he refuted the views of this man, too. Then he said:

From off a tree beneath whose shade a man would sit and rest,

‘Twere treachery to cut a branch. False friends we both detest.

But if occasion should arise, then go destroy that tree.

That monkey then, to serve my needs, was rightly slain by me.

If such the creed you hold and this be doctrine true,

Then was my action right when I that monkey slew.

Could you but only see how wicked is your creed,

You would no longer then with reason blame my deed.

In this way he refuted the doctrine of this man, too.

And now that all five heretics were dumbfounded and bewildered, he addressed the king. He said, “Sire, these fellows with whom you go about are thieves who plunder your realm. Oh! Fool that you are, by consorting with fellows such as these both in this present world and that which is to come, you will meet with great sorrow.” And so saying he taught the king the Dharma. He said:

This man claims, “There is no cause.” Another, “One is Lord of all.”

Some hold, “Each deed was done of old.” Others, “All worlds to ruin fall.”

These and the Kshatriya heretics are fools who think that they are wise,

Bad men are they who commit misdeeds and wickedly advise,

Evil communications will result in pains and penalties.

Now by way of illustration, enlarging on the text of his sermon, he said:

A wolf disguised as ram of old

Drew unsuspected near the fold.

The panic-stricken flock it slew,

Then scampered off to pastures new.

Thus monks and brahmins often use

A cloak, the credulous to abuse.

Some on bare ground all dirty lie,

Some fast, some squat in agony.

Some may not drink, some eat by rule,

As saint each poses, wicked fool.

An evil race of men are they, and fools who think that they are wise,

All such not only are wicked, but others wickedly advise,

Evil communications will result in pains and penalties.

Who say, “No Force exists in anything,”

Deny the Cause of all, disparaging

Their own and others’ acts as vanity, O king,

An evil race of men are they, and fools who think that they are wise,

All such not only are wicked, but others wickedly advise,

Evil communications will result in pains and penalties.

If force exists not anywhere nor acts be good or ill,

Why should a king keep artisans, to profit by their skill?

It is because force does exist and actions good or ill,

That kings keep ever artisans and profit by their skill.

If for a hundred years or more no rain or snow should fall,

Our race, amidst a ruined world, would perish one and all.

But as rains fall and snow withal, the changing year ensures,

That harvest ripens and our land for ages long endures.

The bull through floods a devious course will take,

The herd of cattle straggling in his wake.

So if a leader tortuous paths pursue,

To base ends will he guide the vulgar crew,

And the whole realm an age of license rue.

But if the bull a course direct shall steer,

The herd of cows straight follow in his rear.

So should their chief to righteous ways be true,

The common folk injustice will eschew,

And through the realm shall holy peace ensue.

Who plucks the fruit before it has well ripened on the tree,

Destroys its seed and never knows how sweet the fruit may be.

So he that by unrighteous rule his country has destroyed,

The sweets that spring from righteousness has never once enjoyed.

But he that lets the fruit he plucks first ripens on the tree,

Preserves its seed and knows full well how sweet the fruit may be.

So he, too, by his righteous rule that has preserved the land,

How sweet the fruits of justice are can fully understand.

The warrior king that o’er the land unrighteous sway shall wield

Will suffer loss in plant and herb, whate’er the ground shall yield.

So should he spoil his citizens so apt by trade to gain,

A failing source of revenue will his treasury drain.

And should he offend his soldiers, so skilled to rule the fight,

His army will fall off from him and tear him from his might.

So should he wrong a sage or saint, he meets his due reward,

And through misdeeds, howe’er high born, from heaven will be debarred.

And should a wife by wicked king, though innocent, be slain,

He suffers in his children and in hell is racked with pain.

Be just to town and country folk and treat your soldiers well,

Be kind to wife and children and let saints in safety dwell.

A monarch such as this, O sire, if free from passion found,

Like Indra, lord of Asuras, strikes terror all around.

The Great Being—having thus taught the Dharma to the king—summoned the four young princes and admonished them. He explained the king’s action to them, and he said, “Ask the king’s pardon.” And having persuaded the king to forgive them, he said, “Sire, from now on, do not accept the statement of slanderers without weighing their words. Do not be guilty of any similar deed of violence. And as for you young princes, do not act treacherously towards the king.” And he thus admonished them all.

Then the king said to him, “Holy sir, it was because of these men that I acted wickedly against you and the queen, and through accepting their statement, I committed this evil deed. I will put all five of them to death.” “Sire, you must not do this.” “Then I will order their feet and hands to be cut off.” “This, too, you must not do.” The king consented, saying, “It is well.” He stripped them of all their property and disgraced them in various ways. He fastened their hair into five locks (a mark of disgrace). Then he put them into fetters and chains, sprinkled cow dung over them, then he drove them out of his kingdom.

After staying there for a few days and admonishing the king, the Bodhisatta implored him to be vigilant. Then he set off for the Himalayas where he developed supernatural power arising out of mystic meditation (jhāna). And for as long as he lived, he cultivated the Perfect States (brahma vihārās), then he was reborn in the Brahma world.

The Master here ended his lesson, saying, “Not now only, brothers, but in the past, also, the Tathāgata was wise and crushed all disputants.” Then he identified the birth: “At that time the five heretics were Purāṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Pakudha Kaccāna, Ajita Kesakambalī, Nigaṇtḥa Nāthaputta, the tawny dog was Ānanda, and I was the wandering mendicant Mahābodhi.”

(Purāṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Pakudha Kaccāna, Ajita Kesakambalī, Nigaṇtḥa Nāthaputta were contemporaries of the Buddha who held these views.)