Jataka 532

Sona Nanda

Sona and Nanda

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is a story about two brothers, Sona and Nanda. Sona is the Bodhisatta in a previous life. They are caring for their parents, but Nanda keeps providing the parents with poor quality wild fruits. Then they won’t eat the good food provided by Sona. So Sona forbids his younger brother from gaining the merit he might otherwise gain by caring for his parents.

Nanda then goes through a lengthy process to get his brother’s forgiveness. This is a story that tells you a lot about Indian society and the pecking order in families. Naturally Sona finally forgives Nanda, of course, but it takes quite an effort to get to that point.

There are some other interesting footnotes, such as the fact that caring for your mother brings greater merit than caring for your father. And near the end the Buddha gives a lengthy homage to motherhood. Both the Indian and Buddhist traditions place a lot of emphasis on family, particularly respect for parents.

If you think the Buddha’s behavior is less than exemplary in this story, you would not be alone. The Jataka Tales are full of the Buddha’s less than perfect behavior in previous lives. This is part of their purpose. You see the Buddha as a human being, just like you and me. And just as the Buddha overcame his mistakes and errors in judgment to become enlightened, so can you.

“Deva or minstrel-god?” The Master told this story while he was living at Jetavana. It is about a monk who supported his mother. The circumstances that led up to it were the same as that related in the Sāma Birth (Jātaka 540). But on this occasion the Master said, “Brothers, do not take offence at this monk. Sages of old, though they were offered rule over all India, refused to accept it and supported their parents.” And so saying, he told them this story from the past.

Once upon a time the city of Benares was known as Brahmavaddhana. At that time a king named Manoja reigned there. (See Manoja Jātaka, number 397.) A certain Brahmin magnate with a worth of eighty crores (one crore is ten million rupees) had no heir. His brahmin wife at the bidding of her lord prayed for a son. And so the Bodhisatta, who was being reborn from the Brahma world, was conceived in her womb. At his birth, they called him young Sona.

By the time he could run alone, another being left the Brahma world. He, too, was conceived by her. When he was born, they called him young Nanda. As soon as they had been taught the Vedas and had attained proficiency in the liberal arts, the brahmin, observing how handsome the boys were, addressed his wife. He said, “Lady, we will unite our son, the youthful Sona, in the bonds of wedlock.” She readily assented and reported the matter to her son. He said, “I have had quite enough of the household life. But as long as you live, I will take care of you. And on your death, I will withdraw to the Himalayas and become an ascetic.” She reported this to the brahmin. And after they had spoken to him again and again, they failed to change his mind.

Then they spoke to the young Nanda. They said, “Dear son, will you take up the household?” He answered, “I will not pick up what my brother has rejected as if it were a lump of phlegm. I, too, on your death will go with my brother and join the ascetics.” The parents thought, “If they—even though they are quite young—give up the desires of the flesh, why should not all of us adopt the ascetic life?” They said, “Dear son, why talk of becoming ascetics when we are dead? We will all take the vows now.”

They reported their intention to the king. They gave all their wealth to charity. They freed their slaves and distributed all they owned to their kinsfolk. Then all four of them left the city of Brahmavaddhana. They built a hermitage in the Himalaya region in a pleasant grove. It was near a lake that was covered by the five kinds of lotus. And there they lived as ascetics, and the two brothers cared for their parents.

Early one morning, they brought pieces of stick to them to brush their teeth and water with which to rinse their mouths. They swept out the hut—cell and all—and supplied them with water to drink. They brought them sweet berries from the wood to eat. They provided them with hot and cold water for their bath. They dressed their matted locks, shampooing their feet and rendering them all similar services.

As time passed, the sage Nanda thought, “I shall have to provide all kinds of fruit as food for my father and mother.” Whatever ordinary fruit he had gathered on the spot either yesterday or even the day before that, he would bring in the early morning and give to his parents to eat. They ate it, and after rinsing their mouths, they observed a fast. But the wise Sona went a long distance and gathered sweet and ripe fruit and offered it to them. They would say, “Dear son, we ate early this morning. We ate what your younger brother brought us, and we are now fasting. We have no need of this fruit now.” So his fruit was not eaten but was all wasted. And on the next day and so on, it was the same.

Because he possessed the five Supernatural Faculties (1. the ability to go anywhere at will, 2. the ability to see anything from anywhere, 3. the ability to hear any sound from anywhere, 4. the ability to know the thoughts of other minds, 5. the ability to know past lives), he travelled a long distance to fetch the fruit, but they still refused to eat it. Then the Great Being thought, “My father and mother are very delicate, and Nanda brings them all sorts of unripe or half ripe fruit for them to eat. If this continues, they will not live long. I will stop him from doing this.” So he said to them, “Nanda, from now on, when you bring them fruit, you wait until I come, and we will both supply them with food.”

But despite what the Great Being said, Nanda only wanted merit for himself. He paid no heed to his brother’s words. The Great Being thought, “Nanda is disobeying me: I will send him away.” Then—thinking he would watch over his parents by himself—he said, “Nanda, you are past teaching and ignore the words of the wise. I am the elder. My father and mother are my charge. I alone will watch over them. You cannot stay here. You must leave.” Then he snapped his fingers at him.

After being dismissed in this way, Nanda could not remain in his brother’s presence. Nanda bid him farewell. Then he went to his parents and told them what had happened. He retired into his hut of leaves. He fixed his gaze on the mystic circle (a symbol of focus in meditation), and on that very day he developed the five Supernatural Faculties and the eight Attainments (jhānas). He thought, “I can fetch precious sand from the foot of Mount Sineru and sprinkle it in the cell of my brother’s hut. In this way I can ask his forgiveness. If this does not work, I will fetch water from Lake Anotatta and ask him to forgive me. If this still does not work and if my brother does not pardon me for the sake of heavenly beings, I will bring the four Great Kings and Sakka and ask for his forgiveness. If this still does not work, I will bring Manoja—the chief king in all India—and the rest of the kings, and I will beg him to forgive me. If I am successful, the fame of my brother’s virtue will spread throughout India and be blazed abroad as the sun and moon.”

Using his magic power, he traveled to the city of Brahmavaddhana where he landed at the door of the king’s palace. He sent a message to the king, saying, “An ascetic wishes to see you.” The king said, “What has an ascetic to do with me? He must have come for some food.” He sent Nanda rice, but he would have none of it. Then he sent husked rice and garments and roots, but he would have none of them. At last, he sent a messenger to ask him why he had come. In answer to the messenger he said, “I have come to serve the king.” The king, on hearing this, sent back word. “I have plenty of people to serve me. Tell him to do his duty as an ascetic.” When he heard this, Nanda said, “By my power I will get the sovereigns from over all India and present them to your king.”

When the king heard this he thought, “Ascetics, truly, are wise. They certainly know some clever tricks.” Then he summoned him to his presence and assigned him a seat. He saluted him and asked, “Holy sir, will you, as they tell us, gain rule over all India and grant it to me?” “Yes, sire.” “How will you manage it?” “Sire, I will do this without shedding the blood of anyone, not even so much as a tiny fly would drink. And I will do this without wasting your treasure. By my own magic power, I will gain total sovereignty and turn it over to you. Only, without a moment’s delay, you must venture forth this very day.”

The king believed his words and set out, escorted by an army corps. If it was hot for the army, the sage Nanda used his magic to create shade and make it cool. If it rained, he did not allow the rain to fall on the army. He fended off a hot wind. He moved away any stumps and thorns in the road and defended them from every kind of danger. He made the road as level as the circle used in the Kasiṇa rite (an object used for developing concentration), and spreading a skin, he sat cross-legged on it in the air, and in this way he moved in front of the army.

They first came to the Kosala kingdom. They pitched camp near the city. Then he sent a message to the king of Kosala. They told him to either give battle or yield himself to his power. The king was enraged and said, “What then, am I not a king? I will fight you!“ He went out at the head of his forces, and the two armies engaged in battle. The sage Nanda spread out the antelope skin on which he sat between the two armies. Using his magic powers, he caught all the arrows shot by the combatants on both sides. Not a single soldier in either army was wounded by a shaft. And when all the arrows in their possession were spent, both armies stood helpless. The sage Nanda went to the Kosala king and reassured him, saying, “Great king, do not be dismayed. There is no danger threatening you. The kingdom will still be yours. You only have to submit to King Manoja.”

He believed what Nanda said and agreed to do so. Then he conducted him into the presence of Manoja, where Nanda said, “The king of Kosala submits to you, sire. Let the kingdom remain his.” Manoja readily assented, and receiving his submission, he marched with the two armies to the kingdom of Aṇga. He took Aṇga, and then he took Magadha in the kingdom of that name. And by these means he made himself master of the kings of all India. And accompanied by them, he marched straight back to the city of Brahmavaddhana.

It took him seven years, seven months, and seven days to take the kingdoms of all the kings. He had all manner of food, both hard and soft, from each royal city brought to the kings, one hundred and one in number. For seven days he held a great celebration with them. The sage Nanda thought, “I will not show myself to the king until he has enjoyed the pleasures of sovereignty for seven days.” He went off on his alms rounds in the country of the Northern Kurus. He lived for seven days in the Himalayas at the entrance of the Golden Cave.

On the seventh day Manoja, after contemplating his great majesty and might, thought, “This glory was not given to me by my father and mother or by anyone else. It manifested through the ascetic Nanda. Surely it has been seven days since I have seen him. Where in the world can the friend be that bestowed this glory on me?” He called to mind the sage Nanda. And Nanda, knowing that he was remembered, came and stood before him in the air. The king thought, “I do not know whether this ascetic is a man or a deity. If he is a man, I will give him the sovereignty over all India. But if he is a divinity, I will pay him the honor due to a god.” And to understand his nature, he spoke the first stanza:

Deva or minstrel-god are you, or do we happily see

Sakka, to cities bountiful, or mortal-born may be,

With magic powers endued? Your name we want to learn from thee.

On hearing his words, Nanda declared his nature, repeating a second stanza:

No deva I, no minstrel-god, nor Sakka do you see,

A mortal I with magic powers. The truth I tell to thee.

When he heard this, the king thought, “He says he is a human being. Even so he has been useful to me. I will satisfy him by paying him great honor.” He said:

Great service you have brought to us, beyond all words to tell,

Midst floods of rain no single drop upon us ever fell.

Cool shade you did create for us, when parching winds arose,

From deadly shaft you did us shield, amidst our countless foes.

Next many a happy realm you made me as a sovereign lord,

Over a hundred kings became obedient to our word.

What from our treasures you shall choose, we cheerfully resign,

Cars yoked to steeds or elephants, or nymphs attired so fine,

Or if a lovely palace be your choice, it shall be thine.

In Aṇga realms or Magadha if you desire to live,

Would rule Avanti, Assaka—this too we gladly give.

Yea e’en the half of all our realm we cheerfully resign,

Say but the word, what you would have, at once it shall be thine.

Hearing this, sage Nanda, explained his wishes. He said:

No kingdom do I crave, nor any town or land,

Nor do I seek to win great riches at your hand.

“But if you have any affection for me,” he said, “do my bidding in this one thing.”

Beneath your sovereign sway my aged parents dwell,

Enjoying holy calm in some lone woodland cell.

With these old sages I’m allowed no merit to acquire,

If you and yours would plead my cause, Sona would cease his ire.

Then the king said to him:

Gladly in this will I perform, O brahmin, your behest,

But who are they that I should take to further your request?

The sage Nanda said:

More than a hundred householders, rich brahmins too I name,

And all these mighty warrior chiefs of noble birth and fame,

With King Manoja, are enough to satisfy my claim.

Then the king said:

Go, harness steeds and elephants and yoke them to the car,

Go, fling my banners to the wind, from carriage-pole and bar,

I go to seek where Kosiya, the hermit, dwells afar.

Equipped then with his fourfold host the king marched out to seek

Where he did dwell in charming cell, a hermit mild and meek.

These verses were inspired by Perfect Wisdom.

On the day when the king reached the hermitage, the sage Sona reflected, “It has now been more than seven years, seven months and seven days since my young brother left us. Where can he possibly be?” And looking with the divine eye, he saw him and said to himself, “He is coming with a hundred and one kings and an escort of twenty-four legions to beg my pardon. These kings and their retinues have witnessed many marvelous things done by my young brother. And being ignorant of my supernatural power they will say of me, ‘This false ascetic overestimates his power and measures himself with our lord.’ With such boasting, they will become destined to be reborn in hell. I will give them a display of my magical powers.”

He placed a carrying-pole in the air. It did not touch his shoulder any closer than an interval of four inches. He travelled in space, passing close by the king, to fetch water from Lake Anotatta. But the sage Nanda, when he saw him coming, did not have the courage to show himself. He disappeared on the spot where he was sitting, escaping and hiding himself in the Himalayas.

When he saw Sona approaching in the comely guise of an ascetic, King Manoja spoke this stanza:

Who goes to fetch his water through the air at such a pace,

With wooden pole not touching him by quite four inches space?

Having been addressed, the Great Being spoke a couple of stanzas:

I’m Sona, from ascetic rule I never go astray

My parents I unweariedly support by night and day.

Berries and roots as food for them I gather in the wood,

Ever recalling to my mind how they once brought me good.

Hearing this, the king wished to make friends with him. He spoke another stanza:

We want to reach the hermitage where Kosiya does dwell,

Show us the road, good Sona, which will lead us to his cell.

Then the Great Being used his supernatural power to create a footpath leading to the hermitage. Then he spoke this stanza:

This is the path, mark well, O king, that clump of darkish green,

There midst a grove of ebon trees the hermitage is seen.

(“Ebon” means “ebony.”)

Thus did the mighty sage instruct these warrior kings, and then

Once more he travelled through the air and hurried home again.

Next having swept the hermitage he sought his sire’s retreat,

And waking up the aged saint he offered him a seat.

“Come forth,” he cried, “O holy sage, be seated here, I pray,

For high-born kings of mighty fame will pass along this way.”

The old man having heard his son his presence thus implore,

Came forth in haste from out his hut and sat him by the door.

These verses were inspired by Perfect Wisdom.

And the sage Nanda went to the king at the very moment when the Bodhisatta reached the hermitage, bringing with him water from Anotatta. Nanda pitched their camp not far from the hermitage. Then the king bathed and arrayed himself in all his splendor, and—escorted by one hundred and one kings—he went with the sage Nanda in great state and glory. He entered the hermitage to beg the Bodhisatta to forgive his brother. Then the father of the Bodhisatta, on seeing the king approach them, asked the Bodhisatta what was happening, and he explained the matter to him.

The Master, in making this clear, said:

On seeing him all in a blaze of glory standing near,

Surrounded by a band of kings, thus spoke the aged seer.

Who marches here with tabour, conch, and beat of sounding drums,

Music to cheer the heart of kings? Who here in triumph comes?

(A “tabour” is a drum.)

Who in this blaze of glory comes, with turban-cloth of gold,

As lightning bright, and quiver-armed, a hero young and bold?

Who comes all bright and glorious, with face of golden sheen,

Like embers of acacia wood, aglow in furnace seen?

Who comes with his umbrella held aloft in such a way,

That it with ribs so clearly marked wards off the sun’s fierce ray?

Who is it, with a yak-tail fan stretched forth to guard his side,

Is seen, like some wise sage, on back of elephant to ride?

Who comes in pomp and majesty of parachutes all white,

And mail-clad steeds of noble strain, encircling left and right?

Who comes to us, surrounded by a hundred kings or more,

An escort of right noble kings, behind him and before?

With elephants, with chariots and with horse and foot brigade,

Who comes with all the pomp of war, in fourfold host arrayed?

(The “fourfold” host is infantry, cavalry, chariots, and elephants.)

Who comes with all the legions vast that follow in his train,

Unbroken, limitless as are the billows of the main?

It is Manoja, king of kings, with Nanda here has come,

As though ‘twere Indra, lord of heaven, to this our hermit home.

His is the mighty host that comes, obedient in his train,

Unbroken, limitless as are the billows of the main.

The Master said:

In robe of finest silk arrayed, with sandal oil bedewed,

These kings approach the saintly men in suppliant attitude.

With a salutation, King Manoja took his seat apart. They exchanged friendly greetings. Then the king spoke a couple of stanzas:

O holy men, we trust that you are prosperous and well,

With grain to glean and roots and fruit abundant where you dwell.

Have you been much by flies and gnats and creeping things annoyed,

Or from wild beasts of prey have you immunity enjoyed?

Then these stanzas were spoken by them as question and answer:

We thank you, king, and we say this, we prosper and are well,

With grain to glean and roots and fruit abundant where we dwell.

From flies and gnats and creeping things we suffer not annoy,

And from wild beasts of prey we here immunity enjoy.

Many nuts for such as live as hermits here abound,

No harmful sickness that I know has ever here been found.

Welcome, O king, a happy chance directed you this way,

Mighty you are and glorious, what errand brings you, pray?

The tindook and the piyal leaves, and kāsumārī sweet,

And fruits like honey, take the best we have, O king, and eat.

(A “tindook” is an ebony tree. A “piyal” is type of almond tree, and a kāsumārī tree is a type of oak.)

And this cool water from a cave high hidden on a hill,

O mighty monarch, take of it, drink if it be your will.

Accepted is your offering by me and all, but pray

Give ear to what wise Nanda here, our friend, has got to say.

For all of us in Nanda’s train as suppliants come to thee,

To beg a gracious hearing for poor Nanda’s humble plea.

The sage Nanda rose from his seat. He saluted his father and mother and brother, and, talking with his followers, he said:

Let country folk, a hundred odd, and brahmins of great fame,

And all these noble warrior chiefs, illustrious in name,

With King Manoja, our great lord, all sanction this my claim.

The Yakkhas in this hermitage that are assembled here,

And woodland spirits, old and young, to what I say give ear.

My homage paid to these, I next this holy sage address,

In me a brother you did err as your right hand possess.

To serve my aged parents is the boon from you I ask,

Cease, mighty saint, to hinder me in this my holy task.

Kind service to our parents has long time been paid by thee,

The good approve such deeds—why not yield it in turn to me?

And to the merit I will win the way to heaven is free.

Others there are that know in this the path of duty lies,

It is the way to heaven, as you, O sage, do recognize.

And yet a holy man bars me from merit such as this,

When I by service pray would bring my parents’ perfect bliss.

Thus addressed by Nanda, the Great Being said, “You have heard what he had to say. Now hear me.” And he spoke these stanzas:

All you that swell my brother’s train, my words now hear in turn,

Whoso shall ancient precedent of his forefathers spurn,

Misdeeds against his elders, he, reborn in hell, shall burn.

But they who skilled in holy lore the Way of Truth may know,

Keeping the moral law, shall ne’er to World of Suffering go.

Brother and sister, parents, all by kindred tie allied,

A charge upon the eldest son will evermore abide.

As eldest son this heavy charge I gladly undertake,

And as a pilot guards his ship, the Right I’ll ne’er forsake.

On hearing this all the kings were highly delighted and said, “Today we learn that all the rest of a family are a charge laid upon the eldest,” and they forsook the sage Nanda and became devoted to the Great Being. And singing his praises, they recited two stanzas:

We have found knowledge like a flame that shines at dead of night,

E’en so has holy Kosiya revealed to us the Right.

Just as the sun god by his rays illumines all the sea,

Showing the form of living things, as good or bad they be,

So holy Kosiya reveals the Right to me and thee.

And so it was that although these kings had believed in the sage Nanda for such a long a time—from witnessing his wonderful works—yet the Great Being destroyed their faith in him by the power of knowledge. And causing them to accept his words, he made them of all his obedient servants. Then the sage Nanda thought, “My brother is a wise and clever fellow and mighty in the scriptures. He has gotten the better of these kings and has won them over to his side. But I have no refuge except for him. I will beg him for forgiveness.” And he spoke this stanza:

Since you my suppliant attitude heeds not, nor outstretched hand,

Your humble bond-slave will I be, to wait at your command.

Naturally, the Great Being entertained no angry or hostile feeling towards Nanda. But he rebuked him to humble him after he had spoken so proudly. But now that he heard what he had to say, he was pleased. He was disposed favorably towards him. He said, “Now I forgive you. I will allow you to watch over your father and mother.” And making known his virtues he said:

Nanda, you know the true faith well, as saints have taught it thee,

“‘Tis only noble to be good”—you greatly do please me.

My worthy parents I salute, hear you to what I say,

The charge of you as burden was ne’er felt in any way.

My parents I have tended long, their happiness to earn,

Now Nanda comes and humbly begs to serve you in his turn.

Whiche’er of you two saintly ones would Nanda’s service own,

Speak but the word and he shall come to wait on you alone.

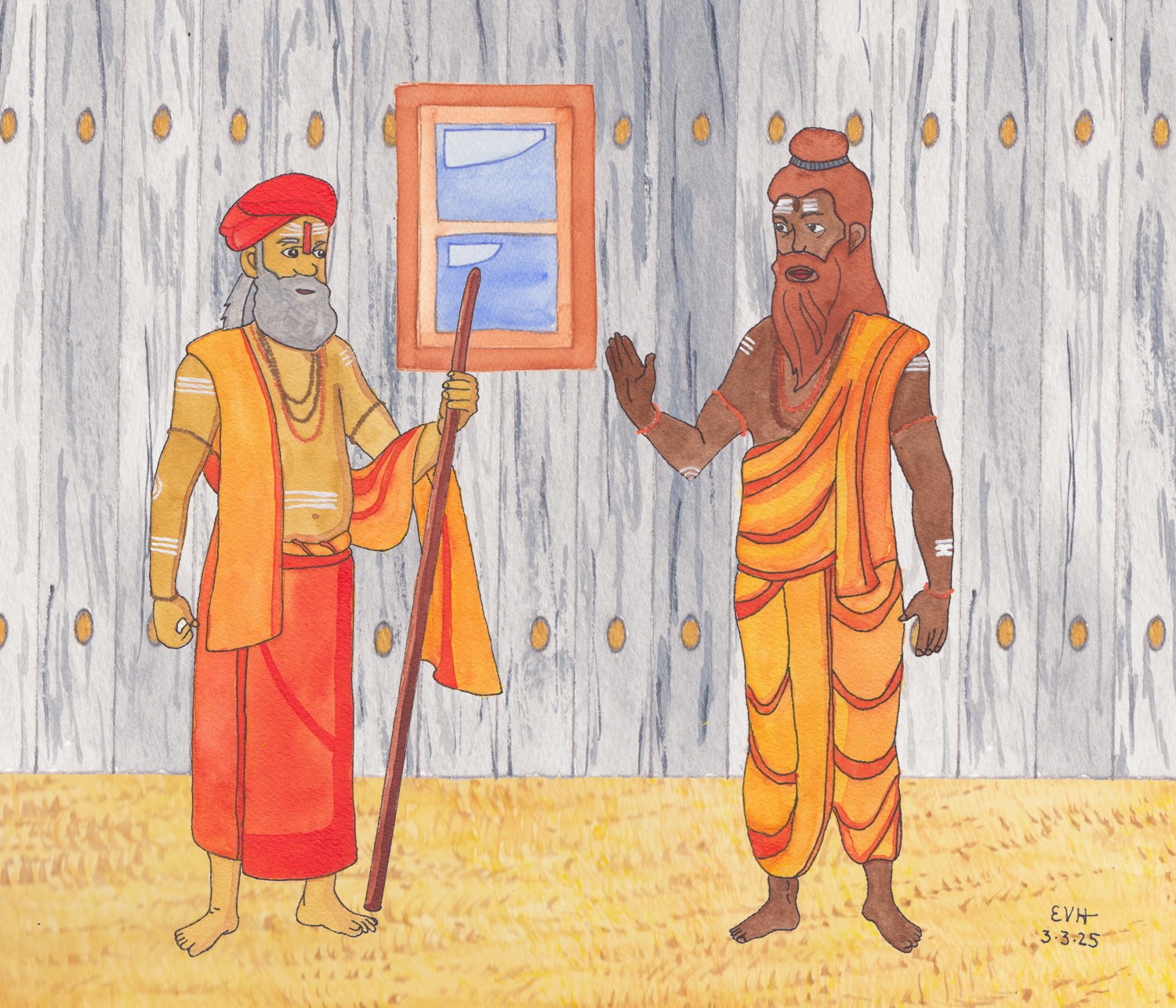

Figure: “Now I forgive you.”

Then his mother rose from her seat and said, “Dear Sona, your younger brother has long been absent from his home. Now that he has returned, I do not venture to ask him myself, for we are altogether dependent upon you. But with your approval I would now like to be allowed to take this holy youth to my arms and kiss him on the forehead.” And to make her meaning clear, she spoke this stanza:

Sona, dear son, on whom we lean, if you do allow this,

Embracing him once more I will the holy Nanda kiss.

Then the Great Being said to her, “Well, dear mother, I give you permission. Go and embrace your son Nanda and smell and kiss his head and soothe the sorrow in your heart.” So she went to the sage Nanda and embraced him before the assembly. She smelled and kissed his head, putting an end to the sorrow in her heart. And addressing the Great Being she spoke this verse:

Just as the tender bo-tree shoot is shaken by the blast,

So throbs my heart with joy at sight of Nanda come at last.

Nanda, I think, as in a dream returned I seem to see,

Half mad and jubilant I cry, “Nanda comes back to me.”

But if on waking I should find my Nanda gone away,

To greater sorrow than before my soul would be a prey.

Back to his parents dear today Nanda at last has come,

Dear to my lord and me alike, with us he makes his home.

Though Nanda to his sire is dear, let him stay where he will,

—You to your father’s wants attend—Nanda shall mine fulfill.

The Great Being agreed to his mother’s words, saying, “So be it.” Then he admonished his brother, saying, “Nanda, you have received the portion of the eldest son. A mother is a great benefit. Be careful in watching over her.” And celebrating a mother’s virtues he spoke two stanzas:

Kind, pitiful, our refuge she that fed us at her breast,

A mother is the way to heaven, and you she loves the best.

She nursed and fostered us with care, graced with good gifts is she,

A mother is the way to heaven, and best she does love thee.

In this way the Great Being told a mother’s virtues in two stanzas. And when his mother had once more taken her seat, he said, “You, Nanda, have got a mother who has suffered things hard to be borne. Both of us have been painfully reared by our mother. Now, you are to carefully watch over her and do not give her sour berries to eat.” To make this clear amid the assembled people, that deeds of great difficulty fell to a mother’s lot, he said:

Craving a child in prayer she kneels each holy shrine before,

The changing seasons closely scans and studies astral lore.

Pregnant in course of time she feels her tender longings grow,

And soon the unconscious babe begins a loving friend to know.

Her treasure for a year or less she guards with utmost care,

Then brings it forth and from that day a mother’s name will bear.

With milky breast and lullaby she soothes the fretting child,

Wrapped in his comforter’s warm arms his woes are soon beguiled.

Watching o’er him, poor innocent, lest wind or heat annoy,

His fostering nurse she may be called, to cherish thus her boy.

What gear his sire and mother have she hoards for him, “May be,”

She thinks, “some day, my dearest child, it all may come to thee.”

“Do this or that, my darling boy,” the worried mother cries,

And when he’s grown to man’s estate, she still laments and sighs.

He goes in reckless mood to see a neighbor’s wife at night,

She fumes and frets, “Why will he not return while it is light?”

If one thus reared with anxious pains his mother should neglect,

Playing her false, what doom, I pray, but hell can he expect?

If one thus reared with anxious pains his father should neglect,

Playing him false, what doom, I pray, but hell can he expect?

Those that love wealth o’ermuch, ‘tis said, their wealth will soon have lost,

One that neglects a mother soon will rue it to his cost.

Those that love wealth o’ermuch, ‘tis said, their wealth will soon have lost,

One that neglects a father soon will rue it to his cost.

Joy, careless ease, laughter and sport, are the sure heritage

Of him that studiously shall tend a mother in old age.

Joy, careless ease, laughter and sport, are the sure heritage

Of him that studiously shall tend a father in old age.

Gifts, loving speech, kind offices, together with the grace

Of calm indifference of mind shown in due time and place—

These virtues to the world are as linch pin to chariot wheel,

These lacking, still a mother’s name to children would appeal.

A mother like the sire should be with reverent honor crowned,

Sages approve the man in whom these virtues may be found.

Thus parents, worthy of all praise, a high position own,

By ancient sages Brahma called. So great was their renown.

Kind parents from their children should receive all reverence due,

He that is wise will honor them with service good and true.

He should provide them food and drink, bedding and clothing meet,

Should bathe them and anoint with oil and duly wash their feet.

For filial services like these sages his praises sound

Here in this world, and after death in heaven his joys abound.

Thus, as though he should set Mount Sineru rolling, did the Great Being bring his lesson to an end. On hearing him all these kings with their hosts became believers. He established them in the five moral laws (Precepts). He exhorted them to be diligent in almsgiving and like virtues. Then he dismissed them. At the end of their days, all of them, after ruling their kingdoms righteously, went to swell the host of heaven. And the sages, Sona and Nanda, as long as they lived, ministered to their parents and became destined to the Brahma world.

Here the Master ended his lesson. Then he taught the Four Noble Truths. At the end of the teaching, the brother who cherished his mother was established in the fruition of the First Path (stream-entry). Then the Master identified the birth: “At that time the parents were members of the Great King’s Court, the sage Nanda was Ānanda, King Manoja was Sāriputta, the hundred and one kings were eighty chief elders and certain others, the twenty-four complete armies were the Buddha’s disciples, and I was the sage Sona.”