Jataka 534

Mahahaṃsa Jātaka

The Great Swan

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by H.T. Francis and R.A. Neil, Cambridge University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This story is nearly identical to the previous Jātaka, number 534. But there are a few interesting twists. First, when Sumukha implicitly disparages women, the Bodhisatta admonishes him. This is particularly interesting in a literature that suffers from (apocryphal) misogyny.

Second, when Sumukha disparages the King, he is forced to admit his error and apologize. These are small but notable quirks in what otherwise might be an overly predictable story.

Since Jātaka 533 and 534 are so similar, it is possible that they are different renderings of the same tale. As Buddhism spread throughout Asia, they most probably were told in slightly different ways. Later they could have been rejoined in the same collection at a central source, probably back—once again—in India. Rather than keep just one version of the story, they may well have incorporated both in order to create a complete collection.

“There go the birds.” The Master told this story while he was living in the Bamboo Grove (Veluvana). It is about the elder Ānanda’s renunciation of life. The introductory story is exactly like one already given, but on this occasion the Master in telling a story of the past relating the following tale.

Once upon a time at Benares, a King named Saṃyama had a chief consort named Khemā. At that time the Bodhisatta had a following of 90,000 geese. They lived on Mount Cittakūṭa. Now at daybreak one day Queen Khemā had a vision. Some gold-colored geese came and perched on the royal throne, and they taught the Dharma with a sweet voice. While the Queen was listening and applauding and had not yet had her fill of the exposition of the Dharma, it became broad daylight. Then the geese finished their discourse and departed by the open window.

The Queen arose in haste. She cried, “Catch them, catch the geese, before they escape!” and in the act of stretching out her hand, she woke. Hearing her words her handmaids said, “Where are the geese?” and softly they laughed.

At that moment the Queen knew that it was a dream. She thought, “I do not see anything that does not exist. Surely there must be golden geese in this world. But if I say to the King, ‘I am anxious to hear the preaching of the Dharma by golden geese,’ he will say, ‘We have never seen any golden geese. There is no such thing as preaching by geese.’ He will take no pains in the matter. But if I say, ‘It is a longing on my part,’ he will search for them in every possible way, and the desire of my heart will be fulfilled.”

So, pretending to be sick, she gave instructions to her servants and lay down. The King, when he had taken his seat on his throne, did not see her at the usual time of her appearance. He asked where Queen Khemā was. When he heard she was sick, he went to her and sat on one side of the bed. He rubbed her back and asked if she were ill. “My lord,” she said, “I am not ill, but I have a great longing.” “Tell me, lady, what you would have, and I will soon get it you.” “Sire, I long to listen to the preaching of the Dharma by a golden goose while it sits on the royal throne with a white umbrella spread over it. I want to pay homage to it with scented wreaths and marks of honor and to express my approval of it. If I should have this, it is well. Otherwise, there is no life in me.”

The King comforted her and said, “If there is such a thing in the world of men, you shall have it. Do not trouble yourself.” He went from the Queen’s chamber and consulted with his ministers. He said, “Mark you, Queen Khemā says, ‘If I can hear a golden goose preach the Dharma, I will live, but otherwise I will die.’ Tell me, are there any golden geese?” “Sire,” they answered, “we have never seen or heard of them.” “Who would know about it?” “The brahmins, sire.” The King summoned the brahmins and asked them, “Is there any such thing as golden geese who teach the Dharma?” “Yes, sire, it has come down to us by tradition that fish, crabs, tortoises, deer, peacocks, and geese, all these are found of a golden color. Among them, they say, the family of Dhataraṭṭha geese are wise and learned. Including men there are seven creatures that are gold-colored.” The King was greatly pleased. He asked, “Where do these scholarly, ruddy geese live?” “We do not know, sire.” “Then who will know?” And when they answered, “The tribe of fowlers,” he gathered all the fowlers in his domain.

He asked them, “My friends, where do gold-colored geese of the Dhataraṭṭha family live?” Then a certain fowler said, “People tell us, sire, by tradition from one generation to another, that they live in the Himalayas on Mount Cittakūṭa.” “Do you know how to catch them?” “I do not know, sire.” He summoned his wise brahmins, and after telling them that there were golden geese on Cittakūṭa, he asked if they knew any way to catch them. They said, “Sire, what need is there for us to go and catch them? We will execute a plan that will bring them close to the city, and then we will catch them.” “What is this plan?” “On the north of the city, sire, you are to dig a lake three leagues in extent, a safe and peaceful spot. Fill it with water. Plant all manner of grain and cover the lake with the five kinds of lotus. Then hand it over to the care of a skillful fowler and do not let anyone else approach it. Stationing men at the four corners and have it proclaimed as a sanctuary lake. All manner of birds will land there. And these geese, hearing from one another how safe this lake is will visit it and then you can have them caught, trapping them with nooses.”

When the King heard this, he had a such a lake created in the place they mentioned. He summoned a skilled fowler who he presented with 1,000 gold coins. Then he said, “From now on, give up your occupation. I will support your wife and family. Carefully guard this peaceful lake and drive everyone else away from it. Have it declared at the four corners as a sanctuary and say that all the birds that come and go are mine. And when the golden geese arrive, you will receive great honor.” With these words of encouragement, the King put him in charge of the sanctuary lake.

From that day on the fowler acted just as the King had instructed him. He watched over that place, and as the one who kept the lake in peace, he came to be known as the fowler “Khema” (Peace). All manner of birds landed there. It was communicated from one bird to another that the lake was peaceful and secure. Different kinds of geese began to arrive. First came the grass geese. Then because of their report, the yellow geese came. They were followed by the scarlet geese, the white geese, and the Oka geese. On their arrival, Khemaka reported to the King. “Five kinds of geese, sire, have come, and they are continually feeding in the lake. Now that the pāka geese have arrived, in a few days the golden geese will be coming. Do not worry, sire.”

When he heard this, the King made a proclamation in the city by beat of drum that no one was to go there. Anyone who did would suffer a mutilation of hands and feet and the destruction of his household goods. And so, from that time on, no one went there.

Now the pāka geese lived not far from Mount Cittakūṭa in Golden Cave. They are very powerful birds, and as with the Dhataraṭṭha family of geese, the color of their body is distinctive. But the daughter of the king of the pāka geese is gold-colored. So her father, thinking she was a fitting match for the Dhataraṭṭha king, sent her to be his wife. She was dear and precious in her lord’s eyes, and because of this the two families of geese became very friendly.

Now one day the geese that attended to the Bodhisatta asked the pāka geese, “Where are you getting your food now?” “We are feeding near Benares, on a safe piece of water. Where do you go?” “To such and such a place,” they answered. “Why don’t you come to our sanctuary? It is a charming lake, teeming with all manner of birds. It is covered with five kinds of lotus. It is abundant with grains and fruits. It buzzes with swarms of many different bees. At each of its four corners is a man to proclaim perpetual immunity from danger. No one is allowed to come near to it, much less to injure another.” And in this way they sang the praises of the peaceful lake.

On hearing what the pāka geese said, they told Sumukha. They said, “They tell us that there is a peaceful lake near Benares. That is where the pāka geese go and feed. Tell the Dhataraṭṭha king, and, if he allows us, we, too, will go and feed there.” Sumukha told the king, who thought, “Men, truly, are full of tricks. They are skilled in scheming. There must be some reason for this. In the long past there has never been such a lake. It must have been made now to catch us.”

He said to Sumukha, “Do not let going there meet with your approval. This lake was not constructed by them in good faith. It was made to catch us. Men surely are cruel and versed in scheming. Keep to your own feeding grounds.”

For a second time the golden geese told Sumukha they were anxious to visit the Lake of Peace, and once again he reported their wishes to the king. The Great Being thought, “My kinsfolk must not be disturbed because of me. We will go there.” So accompanied by 90,000 geese, he went and browsed there. He conducted himself in the manner of geese, and then he returned to Cittakūṭa.

After they had fed and left, Khemaka went and reported their arrival to the King of Benares. The King was highly pleased. He said, “Friend Khemaka, try and catch one or two geese, and I will bestow great honor on you.” With these words he paid his expenses and sent him away. Returning there the fowler seated himself in a skeleton pot and watched the movements of the geese.

Bodhisattas are free from all greed. Therefore, the Great Being started feeding from the spot where he landed. Then he went on eating the paddy in due order. All the others wandered about, eating here and there. So the fowler thought, “This goose is free from greed. This is the one I must catch.”

On the next day, before the geese had landed on the lake, he went to the place nearby and hid himself in the framework of his pot. He remained there sitting and looking through a chink in the frame. At that moment the Great Being—escorted by 90,000 geese—came down on the same spot where he had landed the day before. And sitting down at the limit of yesterday’s feeding ground, he went on browsing. The fowler looked through a chink in his cage, and seeing the extraordinary beauty of the bird, he thought, “This goose is as big as a wagon. It is gold-colored, and its neck is encircled with three stripes of red. Three lines run down the throat passing along the middle of the belly. Other three stripes run down its back. Its body shines like a mass of gold poised on a string made of the thread of red wool. This must be their king, and this is the one I will seize.”

After feeding over a wide field, the goose king played in the water. Then surrounded by his flock, he returned to Cittakūṭa. For six days he fed in this manner. On the seventh day, Khemaka twisted a big stout cord of black horsehair. He fixed a noose on a stick, and, knowing for certain the goose king would land tomorrow on the same spot, he set the stick on which the snare was mounted in the water.

On the next day the goose king stuck its foot as it landed onto the snare. It grasped the bird’s foot as if a band of iron held it fast in its grip. The bird tried to sever the snare. He dragged it and struck it with all its force. First its gold-colored skin was bruised. Next its flesh—the color of red wool was cut. Then the sinew was severed. Last of all its foot would have been broken, but thinking a maimed body was unbefitting a king, he ceased to struggle. As severe pains set in, he thought, “If I should utter a cry of capture, my kinsfolk will be alarmed, and without feeding properly they will fly away. Being half-starved they would drop into the water.” So he withstood the pain. Remaining in the power of the snare, he pretended to feed in the paddy. But when the flock had eaten their fill and were now conducting themselves in the manner of geese, he uttered a loud cry of capture. When the geese heard this, they flew away.

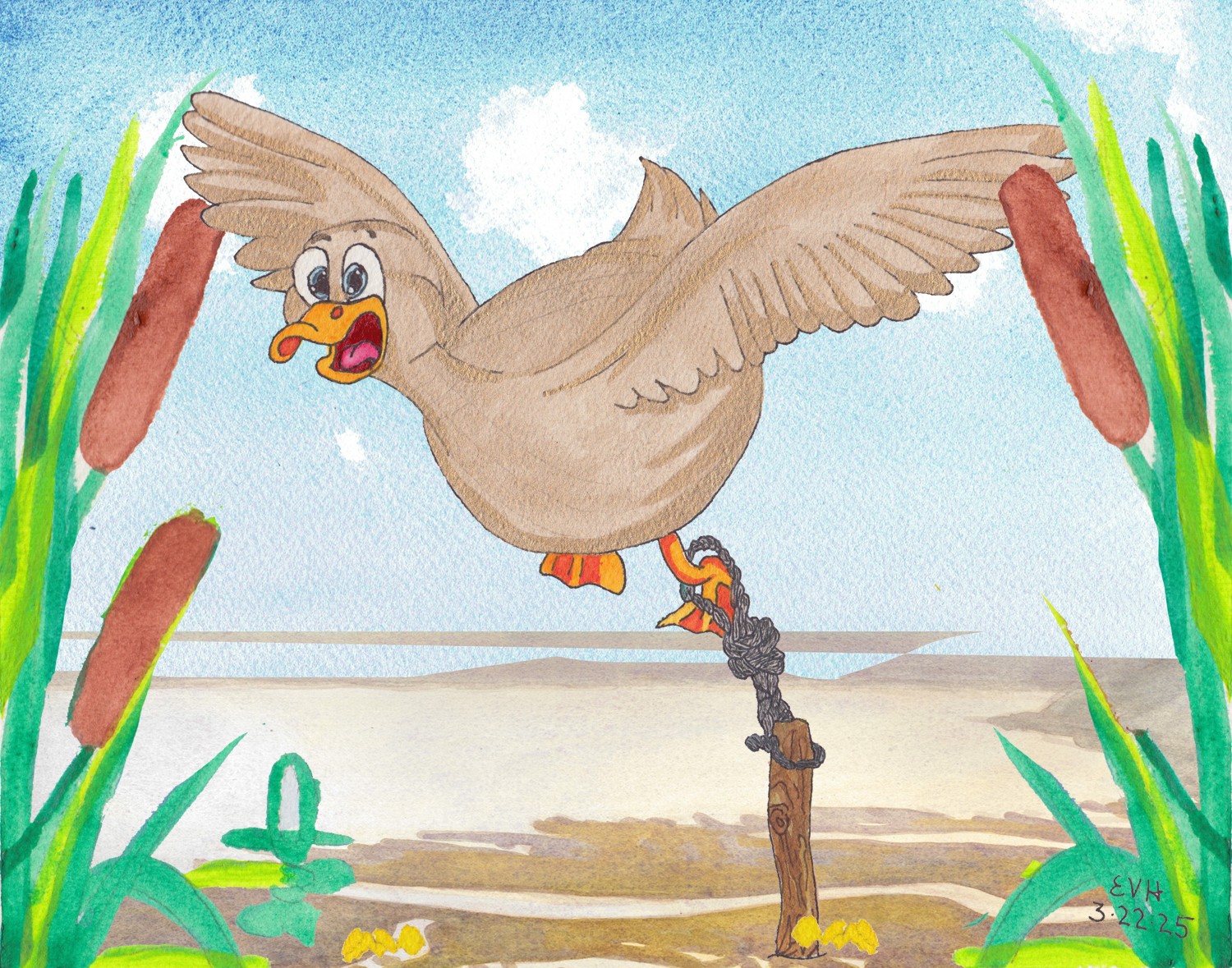

Figure: The Great Being is caught!

Sumukha, too, considered the matter, just as related before. He searched about, and not finding the Great Being in the three main divisions of the geese, he thought, “Truly something terrible must have happened to the king.” He turned back, saying, “Fear not, sire, I will release you at the sacrifice of my own life.” He sat down on the mud, comforting the Great Being. The Great Being thought, “The 90,000 geese have forsaken me and fled. This one alone has returned. I wonder, when the fowler arrives, whether Sumukha, too, will forsake me and flee.” And by way of testing him, stained with blood as he was and resting against the stick fastened to the snare, he repeated three stanzas:

There go the birds, the ruddy geese, all overcome with fear,

O golden-yellow Sumukha, depart! What do stay here?

My kith and kin deserted me, away they all have flown,

Without a thought they fly away. Why are you left alone?

Fly, noble bird, with prisoners what fellowship can be?

Sumukha, fly! nor lose the chance, while you may yet be free.

On hearing this, Sumukha thought, “This goose king is ignorant of my real nature. He thinks I am a friend who speaks words of flattery. I will show him how loving I am,” and he repeated four stanzas:

No, I’ll not leave you, royal goose, when trouble makes its cry,

But stay I will, and by your side will either live or die.

I will not leave you, royal bird, when trouble makes its cry,

Nor join in such ignoble act with others, no, not I.

I’m one in heart and soul with you, playmate and friend of old,

Of all your host, O noble king, famed as the leader bold.

Returning to your kith and kin what could I have to say,

If I shall leave you to your fate and heedless fly away?

No, I would rather die than live, so base a part to play.

When Sumukha had uttered in four stanzas a lion’s note, the Great Being, making known his merits, said:

Your nature ‘tis, O Sumukha, abiding in the Right,

Ne’er to forsake your lord and friend or safety seek in flight.

Looking on you no thought of fear arises in my mind,

E’en in this sorry plight some way to save me you will find.

While they were talking, the fowler stood on the edge of the lake. He saw the geese flying off in three divisions, and wondering what this meant, he looked at the spot where he had set the snare. There he saw the Bodhisatta leaning on the stick to which the noose was fastened. Overjoyed he readied himself. And taking a club, he hastily drew close and stood before the birds. He was like the fire at the beginning of a cycle, with his head towering above them and his heel planted in the mud.

The Master, to make the matter clear, said:

As thus these noble birds exchanged high thoughts, to them, behold!

All in hot haste, with staff in hand drew near this fowler bold.

Seeing him trusty Sumukha stood up before the king,

His anxious lord in his distress stoutly encouraging.

Fear not, O noble bird, for fears become not one like thee,

An effort I will duly make with justice as my plea,

And soon by my heroic act once more you shall be free.

Sumukha comforted the Great Being. Then he went up to the fowler, and speaking with a sweet human voice he asked, “What is your name, friend?” The fowler answered, “O king of the gold-colored geese, I am called Khemaka.” Sumukha said, “Do not imagine, friend, that you have caught an ordinary goose in your horsehair noose. He is the Dhataraṭṭha king, the chief of 90,000 geese. He is wise and virtuous, and he is skilled in conciliation. He should not be put to death. I will do whatever he was to have done for you. I, too, am gold-colored, and for his sake I will lay down my life. If you are anxious to take his feathers, take mine, or, if you would have anything else of his—skin, flesh, sinew, or bone—take it from my body. Again, supposing you wish to make a tame bird of him, make a tame bird of me, selling me while still alive, or if you would make money, make it by selling me. Do not kill him. He is endowed with wisdom and virtues. If you kill him, you will never escape from hell and similar states of suffering.”

After terrifying the fowler with the fear of hell and making him give ear to his sweet discourse, Sumukha once more went to the Bodhisatta and comforted him. And having heard his words, the fowler thought, “Being a mere bird, as he is, he can do something that is impossible for men. Men cannot remain constant in friendship. Oh! What a wise, eloquent, and holy creature is this!” His whole body was thrilled with joy and ecstasy, and his hair stood erect with wonder. He dropped his stick, and raising his joined hands to his forehead like one worshipping the sun, he stood proclaiming the virtues of Sumukha.

The Master, to make the matter clear, said:

The fowler, hearing what the bird so eloquently said,

With hair erect and folded hands his homage duly paid.

Ne’er was it heard or seen before that, using human speech,

To man in his own tongue a goose sublimest truth should preach.

What is this bird to you, that when the rest have fled and gone,

Though free, beside the captive bird you here are left alone?

When he was asked this question by the evil-minded fowler, Sumukha thought, “He is relenting. To soften his heart still more I will now show him my virtue.” And he said:

He is my king, O foe to birds, his captain chief am I,

I cannot leave him to his fate, while I to safety fly.

Let not this lord of mighty hosts here perish all alone,

Near him my happiness I find, him as my lord I own.

On hearing this sweet discourse of his about duty, the fowler, overjoyed and with hair erect in wonder, thought, “If I should kill this royal goose who is endowed with virtue and good qualities, I will never escape from the four states of suffering (birth, aging, sickness, and death). Let the King of Benares do what he wants with me. I will release this captive as a free gift to Sumukha and let him go.” And he spoke this stanza:

Noble are you, to honor one through whom you still do live,

Fly where you will, to your good lord his freedom now I give.

So saying, the fowler—with kindly purpose—drew near to the Great Being. And bending the stick, he laid the bird on the mud, pulled up the stick, and set him free from the noose. Then he picked up the bird from the lake and lay him on some young kuśa grass. He gently loosened the snare that bound his foot. With a strong affection for the Great Being and with kindly thought, he took some water and washed off the blood, repeatedly wiping it. Then through the power of his charity, nerve was united to nerve, flesh to flesh, and skin to skin. The foot became just as it was before. It could not be distinguished from the other one, and the Bodhisatta sat rejoicing in his original state.

Sumukha, seeing how happy the king was because of his action, was highly delighted. He thought, “This man has rendered us a great service, but we have done nothing for him. If he caught us for the King’s ministers of state and took us to them, he would receive a large sum of money. And if he caught us for himself, he could sell us and still make great gain. I will question him.” So in his desire to render him a service, he put this question to him. He said:

If you for your own purposes did set for us this snare,

Our freedom we accept from you without a thought or care.

But otherwise, O fowler bold, in letting us go free,

Without the king’s permission, sure, ‘twas nought but robbery.

On hearing this the fowler said, “I did not catch you for myself. I was employed by Saṃyama, King of Benares.” He told them the whole story, beginning from the time of the Queen’s seeing a vision down to the time when the King heard of the arrival of the geese. The King said, “Friend Khemaka, try and catch one or two geese, and I will confer great honor on you.” “He sent me off with provisions for my journey.”

On hearing this Sumukha thought, “In setting us free this fowler, disregarding his own livelihood, has done a difficult thing. But if we simply return to Cittakūṭa, neither the supernatural wisdom of the Dhataraṭṭha king nor my act of friendship will be revealed, and the fowler will not receive great honor. The King will not be established in the five moral laws (the Precepts), nor will the Queen’s wish be fulfilled.” So he answered, “Friend, it being so, you cannot let us go. Present us to the King and he will deal with us according to his pleasure.”

To make this clear, he spoke this stanza:

You are the servant of the King, his wishes then fulfill,

King Saṃyama shall deal with us according to his will.

On hearing this the fowler said, “O sirs, let it not be your pleasure to see the King. Kings truly are dangerous beings. They will either make tame geese of you or put you to death.” Then Sumukha said, “Friend fowler, do not trouble yourself about us. With my preaching of the Dharma I made a cruel fellow like you soft-hearted. Why should I not do the same in the case of the King? Kings are wise and understand good words. Quickly take us to the King. But do not carry us as captives. Put us in a cage of flowers and take us in that way. Make a big cage shaded with white lotus for the Dhataraṭṭha king, and for me make a small cage covered with red lotus. Put him in front and me behind, somewhat lower, and take us with all speed and present us to the King.”

Hearing the words of Sumukha, the fowler thought, “In seeing the King, Sumukha must want great honor bestowed on me.” Being highly delighted, he fashioned cages of soft osiers (willow branches). He covered them with lotuses and set out with the birds in the way already described.

To make the matter clear, the Master said:

The fowler, grasping them with both his hands as he was told,

Placed in their cage these ruddy geese with skin of yellow gold.

The goose king now and Sumukha with plumage bright to see,

Safe in their cage the fowler took and off with them marched he.

As soon as the fowler had set off with them, the Dhataraṭṭha goose called to mind his wife, the daughter of the pāka goose king. And addressing Sumukha under the influence of his passion, he lamented.

To make the matter clear, the Master said:

The king on being carried off to Sumukha declared,

“My fair and gracious spouse, I think, is missing me and scared,

If she should hear that I am dead, her life, I fear, might take.

Like heron mourning for its mate by lonely ocean’s shore,

Suhemā—bright as gold her skin—her lord she will miss sore.”

On hearing this Sumukha thought, “This goose, though ready to admonish others for a woman’s sake, under the sway of passion, babbles just as when water is heated or as when (birds) rise up from a bank and devour a field of grain. What if I were by my own wisdom to make clear to him the hindrance of passion and to bring him to his senses?” and he said:

That one so great and peerless thought, a leader of his kind,

Should grieve for bird of female sex shows little strength of mind,

As wind will carry any scent, be it or bad or good,

Or greedy child, as if ‘twere blind eats raw or well-cooked food,

Without true judgement in affairs, poor fool, you cannot see,

What to avoid or what to do in each emergency.

Half mad you speak of womankind as blessed with every grace,

Yet most as common are to those as drunkard’s drinking place.

Sorrow, disease, calamity, like harshest chains to bind,

Mirage, and fraud, the snare of death deep-seated in the mind—

Such women are, who trusts in it is vilest of a kind.

Then the Dhataraṭṭha goose, in his respect for women, said, “You know not the virtues of womankind, but the sages know. They are not deserving of censure.” And by way of explanation, he said:

Truth that sages ascertained, who is there that dares to blame?

Women in this world are born, destined to great power and fame.

They for dalliance are formed, joys of love for them ordained,

Seeds within them germinate, source from them all life’s sustained,

They from whom man draws his breath scarce by man may be disdained.

Are you, Sumukha, alone versed in ways of womankind?

Did you only, moved by fear, this belated wisdom find?

Meeting danger every man bears up bravely ‘midst alarm,

In a crisis sages all strive to shelter us from harm.

Princes then to counsel them glad would have a hero brave,

‘Gainst the shock of adverse fate, apt to counsel, strong to save.

Let not royal cooks, I pray, roast our mangled limbs today,

As its fruit the bamboo kills, us, too, golden plumes might slay.

Free you would not fly from me, captive of your own free will,

Cease from words in danger’s hour, up, a manly part fulfill.

The Great Being, by singing the praises of womankind, reduced Sumukha to silence. But on seeing how distressed he was, he now repeated this stanza to conciliate him:

An effort made such as is due, with justice as your plea,

And by heroic act, dear friend, restore my life to me.

Then Sumukha thought, “He is terrified by the fear of death. He does not know my powers. After seeing the King of Benares and having a little talk with him, I will know what to do. Meanwhile, I will comfort my king,” and he spoke this stanza:

Fear not, O noble bird, for fears become not one like thee,

An effort I will duly make, with justice as my plea,

And soon by my heroic act you shall once more be free.

While they were conversing in the language of birds, the fowler did not understand a single word they said. But carrying them on his pole, he entered Benares. He was followed by a multitude of people who were filled with wonder and amazement. They stretched out their hands in respect. On reaching the door of the palace, the fowler had his arrival made known to the king.

The Master, to make the matter clear, said:

The fowler with his burden to the palace gate drew near,

“Announce me to the King,” he cried, “the ruddy goose is here.”

The doorkeeper went and announced his arrival. The King was highly delighted. He said, “Let him come here at once.” And attended by a crowd of courtiers and seated upon the throne with a white umbrella held over him, he saw Khemaka ascend to the dais with his burden. Then looking at the gold-colored geese, he said, “My heart’s desire is fulfilled.” He gave an order to his courtiers that all due service should be rendered to the fowler.

To make the matter clear, the Master said:

Seeing these birds with holy looks and marks auspicious blessed,

King Saṃyama with words like these his councilors addressed,

“Give to the fowler meat and drink, soft food, apparel brave,

And store of ruddy gold as much as heart of man can crave.”

Elated with joy, the King showed his pleasure. He said, “Go and array the fowler and bring him back to me.” So the courtiers, taking him down from the palace, had his hair and beard trimmed, and when he had taken a bath and had been anointed and was sumptuously arrayed, they brought him into the presence of the King. Then the King conferred on him twelve villages yielding 100,000 gold coins annually, a chariot yoked with thoroughbreds, a large well-equipped house, and very great honor. On receiving so great honor, the fowler, to explain what he had done, said, “This, sire, is no ordinary goose that I have brought to you. This is the king of 90,000 geese. His name is Dhataraṭṭha, and this is his chief captain, Sumukha.” Then the King asked, “How, friend, did you catch them?”

The Master, to make the matter clear, said:

Seeing the fowler highly pleased, the King of Kāsi said,

“If, Khemaka, on yonder lake geese in their thousands fed,

Amidst the throng of kindred fowl, pray, how did you contrive

To single out this lovely bird and capture him alive?”

The fowler answered:

Through seven long days with anxious care in vain I marked the spot,

Searching for that fair goose’s track, concealed within a pot.

Today I found the feeding-ground to which the goose repaired,

And there straightway I set a trap and lo! he soon was snared.

On hearing this the King thought, “This fellow standing at the door and telling his story spoke only of the arrival of the Dhataraṭṭha king. And now he, too, speaks only of this one. What can this mean?” and he spoke this stanza:

Fowler, you speak of only one, yet here two birds I see.

‘Tis some mistake, why would you bring this second bird to me?

Then the fowler said, “There was no change of purpose on my part, nor am I anxious to present the second goose to someone else. Only one bird was caught in the snare I set.” In explanation he said:

The goose with lines like ruddy gold all running down his breast,

Caught in my snare I bring to you, O King, at your request.

This splendid bird himself still free sat by the captive’s side,

The while with kindly human speech his friend to cheer he tried.

In this manner he proclaimed the virtues of Sumukha. “As soon as he knew that the Dhataraṭṭha goose was caught, he stayed and consoled his friend. On my approach he came to meet me. He remained poised in the air, conversing pleasantly with me in human language and telling of the virtues of the Dhataraṭṭha. After softening my heart, he once more took his stand in front of his friend. Then I, sire, on hearing the eloquence of Sumukha, was converted, and I let the Dhataraṭṭha loose. Thus, the release of Dhataraṭṭha from the snare and my coming here with these geese was all due to Sumukha.”

On being told this the King was anxious to hear a sermon from Sumukha. While the fowler was still paying honor to him, the sun set, lamps were lighted, and a crowd of warrior chiefs and others gathered. Queen Khemā, with an escort of diverse bands of dancers, took her seat on the right of the King. Then the King, desiring to persuade Sumukha to speak, uttered this stanza:

Why, Sumukha, hold you your tongue? Is it from awe, I pray,

That in my royal presence you have not a word to say?

Hearing this, Sumukha, to show he was not afraid, said:

I fear not, Kāsi lord, to speak amidst your royal train,

Nor should occasion fit arrive, would I from words refrain.

Hearing this, the King, wanting to make him speak at greater length, admonished him. He said:

No archers clad in mail, no helm, no leather shield I see,

No escort bold of horse or foot, no cars, no infantry.

I see no yellow gold, no town with goodly buildings crowned,

No watch tower made impregnable with moat encircling round,

Entrenched wherein by Sumukha, nothing to fear be found.

When the King had asked why he was not terrified, Sumukha replied in this stanza:

No escort for a guard I want, no town or wealth need I,

‘Midst pathless air we find a way and travel through the sky.

If you were grounded in the truth, we happily would teach

Some useful lesson for your good in wise and subtle speech.

But if you are a liar, false, one of ignoble strain,

This fowler’s words of eloquence appeal to you in vain.

On hearing this the King said, “Why do you speak of me as lying and ignoble? What have I done?” Then Sumukha said, “Well, listen to me,” and he spoke as follows:

At brahmins’ bidding you did make this Khema, lake of fame,

And did to birds at twice five points immunity proclaim.

Within this peaceful pool thus fed with streams serene and pure,

Birds ever found abundant food and lived a life secure.

Hearing this noised abroad we came to visit that fair scene,

And snared by you we found alas! your promise false had been.

But under cover of a lie each act of wicked greed

Forfeits rebirth as man or god, and straight to hell must lead.

In this way, even amid his retinue, he put the King to shame. Then the King said to him, “I did not have you caught, Sumukha, to kill you and eat your flesh. But hearing how wise you were, I was anxious to listen to your eloquence.” And, making the matter clear, he said:

No fault was mine, O Sumukha, nor seized I you through greed,

Your fame for wisdom and deep thought, ‘twas this that caused the deed.

“Happily, if here they may declare some true and helpful word,”

‘Twas so I bade the fowler seize and bring you here, O bird.

On hearing this Sumukha said, “You have acted wrongly, sire,” and he spoke as follows:

We could not speak the word of truth, awed by approaching death,

Nor when in death’s last agony we draw our parting breath.

Who would a bird with bird decoy, or beast with beast pursue,

Or with a text a preacher trap, no base would he eschew.

And whoso utters noble words, intent on action base,

Both here and in the next world sinks from bliss to woeful place.

Be not o’erjoyed in glory’s hour, in danger not distressed,

Make good defects, in trouble strive to do your very best.

Sages arrived at life’s last stage, the goal of death in view,

After a righteous course on earth, to heaven their way pursue.

Hearing this cleave to righteousness, O sire, and straight release

This royal Dhataraṭṭha bird, the paragon of geese.

Hearing this the King said:

Go, fetch some water for their feet, and throne of solid worth,

Lo! from his cage I have set free the noblest bird on earth,

Together with his captain bold, so able and so wise,

Taught to his king in weal and woe ever to sympathize.

Sure such someone right well deserves e’en as his lord to fare,

Just as he was prepared with him both life and death to share.

Hearing the King’s words, they fetched seats for them. And as they sat there, they washed their feet with scented water and anointed them with oil a hundredfold refined.

The Master, in explaining the matter, said:

The royal bird sat on a throne, eight-footed, burnished bright,

All solid gold, with Kāsi cloth o’erspread, a splendid sight.

And next his king sat Sumukha, his trusty captain bold,

Upon a couch with tiger-skin o’erspread, and all of gold.

To them full many a Kāsi lord in golden bowls did bring,

Choice gifts of dainty food to eat, the offerings of their king.

When this food had been served to them, the Kāsi King—to welcome them—took a golden bowl and offered it to them. From it they ate honey and parched grain, and they drank sugar-water. Then the Great Being, taking note of the King’s offering and the grace with which it was made, entered into a friendly conversation with him.

The Master, to clear up the matter, said:

Thinking, “How choice the gifts this lord of Kāsi offered us,”

The bird, skilled in the ways of kings, made his inquiries thus,

Do you, my lord, enjoy good health and is all well with thee?

I trust your realm is flourishing and ruled in equity.

O king of geese, my health is good and all is well with me,

My realm is ever flourishing and ruled in equity.

Have you true men to counsel you, free from all stain and blame,

Ready to die, if need there be, for your good cause and name?

I have true men to counsel me, free from all stain and blame,

Ready to die, if need there be, for my good cause and name.

Have you a wife of equal birth, obedient, kind in word,

With children blessed, good looks, fair name, compliant with her lord?

I have a wife of equal birth, obedient, kind in word,

With children blessed, good looks, fair name, compliant with her lord.

And is your realm in happy case, from all oppression free,

Held by no arbitrary sway, but ruled with equity?

My kingdom is in happy case, from all oppression free,

Held by no arbitrary sway, but ruled with equity.

Do you drive bad men from the land, good men to honor raise,

Or do you righteousness eschew, to follow evil ways?

I drive bad men out from the land, good men to honor raise,

All wickedness I do eschew and follow righteous ways.

Do mark the span of life, O king, how quickly it is sped,

Or drunk with madness do regard the next world free from dread?

I mark the span of life, O bird, how quickly it is sped,

And, standing fast in virtues ten, the next world never dread.

Almsgiving, justice, penitence, meek spirit, temper mild,

Peace, mercy, patience, charity, with morals undefiled—

These graces firmly planted in my soul are clear to see,

Whence springs rich harvest of great joy and happiness for me.

But Sumukha though knowing nought of evil we had done,

Right heedlessly gave vent to words in harsh and angry tone.

Things I knew not were to my charge by this bird wrongly laid,

In language harsh. Herein, I think, scant wisdom was displayed.

On hearing this Sumukha thought, “This virtuous King is angry because I upbraided him. I will win his forgiveness,” and he said:

I spoke against you, lord of men, and that was my mistake,

But when this royal goose was caught my heart was like to break.

As earth bears with all living things, as father with his son,

Do you, O mighty king, forgive the wrong that we have done?

Then the King took the bird up and embraced him. And seating him on a golden stool, he accepted his confession of error. He said,

I thank you, bird, that you should ne’er your nature true conceal,

You’ve broken down my stubborn will, upright are you, I feel.

And with these words the King, being highly pleased with the exposition of the Dharma by the Great Being and with the honest speech of Sumukha, thought, “When one is pleased, one ought to show one’s pleasure.” And yielding his royal splendor, he said to the birds:

Whate’er of silver, gold, and pearls, rich gems and precious gear

In Kāsi’s royal town is stored within my palace here.

Copper and iron, shells and pearls, and jewels numberless,

Ivory, yellow sandal wood, deer skins and costly dress,

This wealth and lordship over all, I give you to possess.

And with these words honoring both birds with the white umbrella, he handed his kingdom over to them. Then the Great Being, conversing with the King, said:

Since you are quick to honor us, be pleased, O lord of men,

To be our Master, teaching us those royal virtues ten.

And then if your approval and consent we happily win,

We would take formal leave of you and go to see our kin.

(The ten royal virtues are generosity, morality, renunciation, honesty, gentleness, asceticism, non-violence, patience, and uprightness.)

He gave them leave to go, and, while the Bodhisatta was still preaching the Dharma, the sun rose.

The Master, to make the matter clear, said:

The livelong night in deepest thought the King of Kāsi spent,

Then to that noble bird’s request straight yielded his consent.

When he had got permission to depart, the Bodhisatta, said, “Be vigilant and rule your kingdom in righteousness.” He established the king in the five moral laws (the Precepts). The king offered them parched corn with honey and sugar water in golden dishes. And when they had finished their meal, he paid them homage with scented wreaths and similar offerings. Then the King lifted the Bodhisatta up high in a golden cage. Likewise, Queen Khemā lifted Sumukha up on high. Then at sunrise they opened the window, and saying, “Sirs, begone,” they let them loose.

The Master, to make the matter clear, said:

Then as sun began to rise and break of day was nearby,

Soon from their sight they vanished quite in depths of azure sky.

The Great Being flew up from the golden cage. He poised in the air and said, “O sire, be not troubled. Be vigilant and abide in our admonition.” In this way, he comforted the King. And taking Sumukha with him, he made straight for Cittakūṭa. Those 90,000 geese flew from the Golden Cave settled on the high table land. When they saw the two birds coming, they set out to meet them, and then they escorted them home. And so, accompanied by a flock of their kinsfolk, they reached the plateau of Cittakūṭa.

The Master, to make the matter clear, said:

Seeing their chiefs all safe and sound returned from haunts of men,

The winged flock with noisy cries welcomed them back again.

Thus circling round their lord in whom they trust, these ruddy geese

Paid all due honor to their king, rejoiced at his release.

While escorting their king, these geese asked him, “How, sire, did you escape?” The Great Being told them of his escape with the help of Sumukha and of the action of King Saṁyama and his courtiers. On hearing this, the flock of geese sang praises of joy, saying, “Long live Sumukha, captain of our host, and long live the King and the fowler. May they be happy and free from sorrow.”

The Master, to make the matter clear, said:

Thus all whose hearts are full of love succeed in what they do,

E’en as these geese back to their friends once more in safety flew.

This has been fully related in the Cullahaṁsa Birth (Jātaka 533).

The Master here ended his story and identified the birth: “At that time the fowler was Channa, Queen Khemā was the nun Khemā, the King was Sāriputta, the goose king’s retinue was the followers of Buddha, Sumukha was Ānanda, and I was the goose king.”