Jataka 11

Lakkhaṇa Jātaka

The Upright Man

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This is another Jātaka Tale where Devadatta gets pretty rough treatment. You may recall that Devadatta was the Buddha’s cousin and a monk. He challenged the Buddha in order to take over the Saṇgha and even tried to kill him. It seems probable that the purpose of these stories is to make Devadatta appear as evil as possible.

“The upright man.” This story about Devadatta was told by the Master in the Bamboo-grove near Rājagaha. The story of Devadatta will be related, up to the date of the Abhimāra employment in the Khaṇḍahāla Jātaka, up to the date of his dismissal from the office of Treasurer in the Cullahaṃsa Jātaka, and, up to the date of his being swallowed up by the earth in the Sixteenth Book in the Samudda-vāṇija Jātaka.

(The incidents listed here are various stories in Devadatta’s life.)

On the occasion now in question, Devadatta, failing to get the Buddha to agree to the Five Points (Devadatta challenged the Buddha’s authority by trying to get him to agree that all monks 1) should live all their lives in the forest, 2) live entirely on alms obtained by begging, 3) wear only robes made of discarded rags, 4) live at the foot of a tree and 5) abstain completely from eating meat), caused a schism in the Saṇgha. He went off with five hundred monks to live at Gayāsīsa. The Master called his two chief disciples (Sāriputta and Moggallāna) and said, “Sāriputta, the five hundred pupils who were perverted by Devadatta’s teaching went off with him. Go with some members of the Saṇgha, preach the Dharma to them, enlighten these wanderers respecting the Paths and the Fruits, and bring them back with you.”

They did as they were asked, preached the Dharma, enlightened the wayward monks respecting the Paths and the Fruits, and came back the next day at dawn with the five hundred monks to the Bamboo-grove. And while Sāriputta was standing there after saluting the Blessed One on his return, the monks spoke to him in praise of the Elder Sāriputta. “Sir, the glory of our elder brother was very bright as he returned with a following of five hundred monks, whereas Devadatta has lost all his followers.”

“This is not the only time, monks, when Sāriputta gained glory after returning with those for whom he is responsible. This happened in the past as well. Likewise, this is not the only time when Devadatta lost his following.”

The monks asked the Blessed One to explain this to them. The Blessed One made clear what had been concealed by re-birth.

Once upon a time in the city of Rājagaha in the kingdom of Magadha there ruled a certain king of Magadha. In those days the Bodhisatta came to life as a buck. Growing up, he lived in the forest as the leader of a herd of a thousand deer. He had two young bucks named Luckie and Blackie. When he grew old, he divided his herd in two. He handed his herd over to his two sons, placing five hundred deer under the care of each of them. And so now these two young bucks were in charge of the herd.

At harvest time in Magadha, when the crops stand thick in the fields, it is dangerous for the deer in the surrounding forests. The peasants are anxious to kill the animals that eat their crops. They dig pitfalls, fix stakes, set stone-traps, and plant snares and other traps, so that many deer are killed.

Accordingly, when the Bodhisatta saw that it was crop time, he sent for his two sons and said to them, “My children, it is now the time when crops stand thick in the fields, and many deer meet their death at this season. We who are old will stay here, but you will each take your herd to the mountainous tracts in the forest and come back when the crops have been harvested.”

“Very good,” said his two sons, and they departed with their herds as their father had asked.

Now the men who live along the route know quite well the times at which deer take to the hills and then return. They lie in wait in hiding places here and there, and they shoot and kill many of them. The dullard Blackie, ignorant of the times to travel and the times to stop, kept his deer on the march early and late, both at dawn and at dusk, approaching the very edges of the villages. And the peasants, in ambush or in the open, destroyed many of his herd. Having caused the destruction of so many deer, he reached the forest with very few survivors.

Luckie on the other hand, being wise and astute and resourceful, never approached the edges of a village. He did not travel by day, or even in the dawn or at dusk. He only moved in the dead of night. As a result, he reached the forest without losing a single head of his deer.

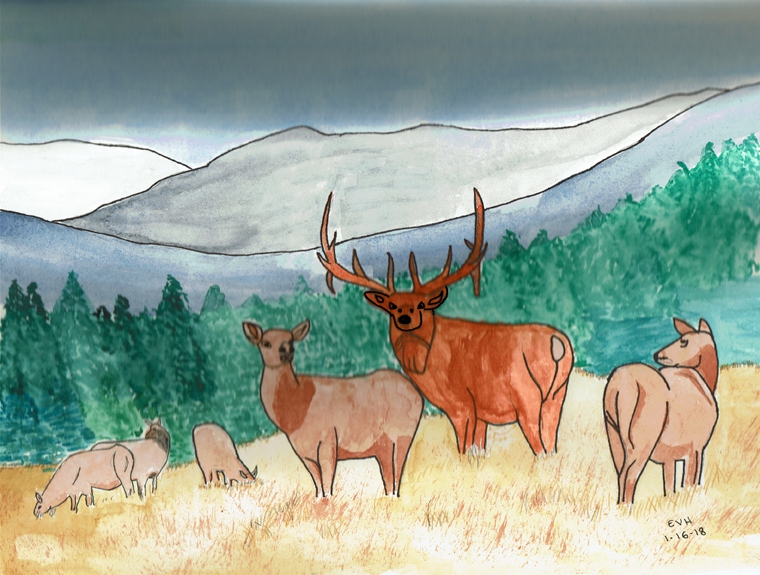

Figure: Luckie Protecting the Herd

They stayed in the forest for four months, not leaving the hills until the crops were harvested. On the way back Blackie repeated his folly and lost the rest of his herd. He returned home solitary and alone. But Luckie had not lost one of his deer. He brought back all five hundred of them. As he saw his two sons returning, the Bodhisatta composed this stanza about the herd of deer:

The upright kindly man gets his reward.

See Luckie leading back his troop of kin,

While here comes Blackie bereft of all his herd.

And this was how the Bodhisatta welcomed his sons. And after living to a ripe old age, he passed away to fare according to his karma.

At the end of his lesson, when the Master had repeated that Sāriputta’s glory and Devadatta’s loss both had had a parallel in bygone days, he showed the connection linking the two stories together. He identified the birth by saying, “Devadatta was the Blackie of those days. His followers were Blackie’s following. Sāriputta was Luckie of those days, and his following were the Buddha’s followers. Rāhula’s mother was the mother of those days, and I myself was the father.”