Jataka 12

Nigrodhamiga Jātaka

Keep Only with the Banyan Deer

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

This Jātaka is the first one in the collection about a nun. Women at the time of the Buddha were little more than slaves. But the Buddha not only started an order of nuns, there were many prominent laywomen in his Saṇgha. One of them, Visākhā, is also in this story.

Also notice that the Buddha does not automatically take the nun into his Saṇgha. Even though he knows that she is innocent of any wrong-doing, he is sensitive to the realities of public opinion. The monks and nuns lived on alms food. They were completely at the mercy of the support of the community. So he organized a process whereby her innocence could be shown in a public way.

I am sure you will not miss the unflattering description of the human body. One of the strongest attachments we have and one of the strongest senses of self-identity that we have is with the human body. This creates a lot of suffering for ourselves and is an important focus in Buddhist practice. The aim is to appreciate and care for the body without becoming attached to it as “me.”

“Keep only with the Banyan Deer.” This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana. It is about the mother of the Elder Prince Kassapa. She was the daughter, we learn, of a wealthy merchant of Rājagaha. She was deeply rooted in goodness, and she scorned all worldly things. She had reached her final existence and within her breast, like a lamp in a pitcher, the certainty of her winning Arahantship glowed.

Even at a very young age, she took no joy in a worldly life. She yearned to renounce the world and to become a nun. With this aim, she said to her mother and father, “My dear parents, my heart takes no joy in a worldly life. I would rather embrace the saving Dharma of the Buddha. Let me take the vows.”

“What, my dear? We are a very wealthy family, and you are our only daughter. You cannot take the vows.”

Even though she asked them again and again, she failed to win her parents’ consent. She thought to herself, “So be it. When I am married into another family, I will get my husband’s consent and take the vows.”

When she came of age, she entered another family. She proved a devoted wife and lived a life of goodness and virtue in her new home. Now it came to pass that she became pregnant, but she did not know it.

There was a festival proclaimed in that city, and everybody kept the holiday. The city was decorated like a city of the gods. But even at the height of the festival, she did not wear any jewelry or fine clothes. Her husband said to her, “My dear wife, everybody is on holiday, but you do not put on your best clothes.”

“My lord and master,” she replied, “the body is filled with thirty-two parts. Why should it be decorated? This body is not sacred. It is not made of gold, jewels, or yellow sandal-wood. It does not take its birth from the womb of lotus-flowers, white or red or blue. It is not filled with any immortal balsam. No. It is bred of corruption and born of mortal parents. The qualities that mark it are the wearing and wasting away, the decay and destruction of the merely transient. It is destined to swell a graveyard and is devoted to lust. It is the source of sorrow and lamentation. It is the home of all diseases, and the storehouse of the workings of karma. It is foul inside and always excreting. Yes, as all the world can see, its end is death, passing to the cemetery, there to be the habitat of worms. What would I gain, my bridegroom, by ornamenting this body? Wouldn’t that be like decorating a latrine?”

“My dear wife,” responded the young merchant, “if you think this body is so foul, why don’t you become a nun?”

“If I am accepted, my husband, I will take the vows this very day.”

“Very good,” he said. “I will get you admitted to the Saṇgha.” And after he gave wonderful gifts and showed hospitality to the Saṇgha, he escorted her with a large following to the monastery and had her admitted as a nun, but of the Saṇgha of Devadatta. Nonetheless, she felt great joy at the fulfillment of her desire to become a nun.

As time went on the other nuns noticed her getting larger. She had swelling in her hands and feet. They said, “Lady, it looks like you are about to become a mother. What does it mean?”

“I cannot tell you, sisters. I only know I have led a virtuous life.”

So the sisters brought her before Devadatta, saying, “Lord, this young gentle-woman, who was admitted as a sister with the reluctant consent of her husband, has now proven to be with child. But whether this happened before her admission to the Saṇgha or not, we cannot say. What should we do now?”

Not being a Buddha and not having any charity, love, or compassion, Devadatta thought, “It will damage my reputation if one of my nuns is pregnant and I forgive the offense. My course is clear. I must expel her from the Saṇgha.” Without any investigation into what had happened, he started forward as if to thrust aside a mass of stone and said, “Away, and expel this woman!”

The sisters arose and with reverent salutation withdrew to their own nunnery. But the girl said to those sisters, “Ladies, Devadatta the Elder is not the Buddha. My real vows were not taken under Devadatta, but under the Buddha, the Foremost of the world. Do not rob me of the path I won with such difficulty. Take me before the Master at Jetavana.” So they set out with her for Jetavana, and traveling over one hundred fifty miles from Rājagaha, they arrived at their destination. There they saluted the Master and told him what had happened.

The Master thought, “Although the child was conceived while she was still a layperson, it will give Devadatta’s followers an excuse to say that the ascetic Gotama has taken a sister expelled by Devadatta. Therefore, to cut short such talk, this case must be heard in the presence of the King and his court.”

So the next day he sent for Pasenadi, King of Kosala, the elder and the younger Anāthapiṇḍika, the lady Visākhā, the great lay-disciple, and other well-known people. In the evening, when the four classes of the faithful were all assembled - monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen - he said to the Elder Upāli, “Go, and clear up the matter of the young sister in the presence of the four classes of my disciples.”

“It shall be done, reverend sir,” said the Elder, and he went before the assembly. Seating himself in his place, he called up Visākhā, the lay-disciple, in sight of the King. He placed the conduct of the inquiry in her hands, saying, “First determine the precise day and month on which this girl joined the Saṇgha, Visākhā. Then determine whether she conceived before or after that date.”

Accordingly the lady had a curtain put up as a screen, behind which she went with the girl. Visākhā determined that the conception had taken place before the girl had become a nun. She reported this to the Elder, who proclaimed the sister innocent before the assembly. And now that her innocence was established, she reverently saluted the Saṇgha and the Master, and she returned with the sisters to her own nunnery.

When her time came, she bore a son who was strong in spirit, for she had prayed at the feet of the Buddha Padumuttara (a previous Buddha) ages ago. One day, when the King was passing by the nunnery, he heard the cry of an infant and asked his courtiers what it meant. They told his majesty that the cry came from the child to which the young sister had given birth. “Sirs,” said the King, “the care of children is a burden to sisters in their holy life. Let us take charge of him.” So by the King’s command the infant was handed over to the ladies of his family and raised as a prince. When the day came for him to be named, he was named Kassapa. But he was known as Prince Kassapa because he was brought up like a prince.

At the age of seven he became a novice monk under the Master, and he became a full monk when he was old enough. As time went on, he became famous as an expounder of the Dharma. So the Master gave him a special status, saying, “Monks, Prince Kassapa is foremost in the Saṇgha in eloquence.” Afterwards, by virtue of the Vammīka Sutta [MN 23] he won Arahantship. His mother also grew to clear vision and became an Arahant. Prince Kassapa the Elder shone in the faith of the Buddha even as the full moon in the mid-heaven.

Now one afternoon when the Tathāgata was returning from his alms-round, he addressed the Saṇgha then went into his perfumed chamber. After his address the monks spent the daytime either in their night-quarters or in their day-quarters until it was evening. When they assembled in the Dharma hall, they said, “Brothers, Devadatta is not a Buddha, and because he had no charity, love, or compassion, he could have ruined the lives of the Elder Prince Kassapa and his reverend mother. But the All-enlightened Buddha, being the Lord of the Dharma and being perfect in charity, love, and compassion, has been their salvation.”

And as they sat there singing the praises of the Buddha, he entered the hall with all the grace of a Buddha, and asked, as he took his. seat, what they were talking about.

“Of your own virtues, sir,” they said, and told him what they had been discussing.

“This is not the first time, brothers,” he said, “that the Tathāgata has proved the salvation and refuge of these two. He did in the past as well.”

The brothers asked him to explain this to them, and he told them what re-birth had hidden from them.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was born as a deer. His fir was the color of gold. His eyes were like round jewels. His horns were silver. His mouth was red as a bunch of scarlet cloth. His four hoofs looked like they were lacquered. His tail was soft and fluffy like a yak’s, and he was as big as a young foal. Attended by five hundred deer, he lived in the forest under the name of King Banyan Deer. And nearby him lived another deer who also had a herd of five hundred deer. His name was Branch Deer, and his fir was as gold as the Bodhisatta.

In those days the King of Benares was very fond of hunting, and he always had meat at every meal. Every day he gathered all of his subjects, townsfolk and country folk alike, to the detriment of their business, and went hunting. His people thought, “This King stops all of our work. Suppose we were to plant food and supply water for the deer in his own pleasure garden. Then we could drive in a number of deer, corral them and deliver them over to the King!”

So they planted grass in the pleasure garden for the deer to eat and supplied water for them to drink and opened up the gate. Then they called out the townsfolk and went into the forest armed with sticks and all manner of weapons to find the deer. They surrounded a large portion of forest to catch the deer within their circle, and in so doing surrounded the places where Banyan and Branch deer were. As soon as they saw the deer, they beat the trees, bushes and ground with their sticks until they drove the herds out of their sanctuaries. Then they rattled their swords and spears and bows with such noise that they drove all the deer into the pleasure garden, and they shut the gate. Then they went to the King and said, “Sire, you put a stop to our work by always going hunting. So we have driven enough deer from the forest to fill your pleasure garden. From now on feed on them.”

After this the King went to the pleasure garden. Looking over the herd, he saw the two golden deer. He granted them immunity.

After that, sometimes the King would go on his own and shoot a deer to bring home. Sometimes his cook would go and shoot one. At first sight of the bow, the deer would dash off trembling for their lives, but after receiving two or three wounds they grew weak and faint and died. The herd of deer told this to the Bodhisatta, who sent for Branch and said, “Friend, the deer are being destroyed in large numbers. At least let them not be needlessly wounded and suffer so much. Let the deer go to the chopping block by turns, one day one from my herd, and next day one from yours. The deer will then go to the place of execution and lie down with its head on the block. In this way the deer will escape being wounded.” Branch agreed, and after that the deer whose turn it was would go and lie down with its neck ready on the block. The cook used to go and carry off only the victim that was there for him.

Now one day it was the turn of a pregnant doe of Branch’s herd, and she went to Branch and said, “Lord, I am with child. When my little one is born, we will both take our turn. But please allow me to be passed over this turn.”

“No, I cannot have another take your turn,” he said. “You must bear the consequences of your own fortune. Be gone!”

Having failed with him, the doe went to the Bodhisatta and told him her story. He answered, “Very well. You go away, and I will see that you skip your turn.”

And then he went himself to the place of execution and lay down with his head on the chopping block. On seeing him the cook cried, “Why here’s the king of the deer who was granted immunity! What does this mean?” And he ran off to tell the King. The moment he heard of it, the King mounted his chariot and arrived with a large following. “My friend the king of the deer,” he said, “Didn’t I promise to spare your life? Why are you lying here?”

“Sire, a doe came to me. She is with child, and she begged me to let her skip her turn. And since I could not pass the doom of one on to another, I will lay down my life for her and take her doom on myself. Do not think that there is anything behind this, your majesty.”

“My lord the golden king of the deer,” said the King, “I have never seen anyone, even among men, so full of charity, love, and compassion as you. Therefore, I am pleased with you. Arise! I spare the lives of both you and her.”

“What about the rest of the deer, O King of men?”

“I spare their lives too, my lord.”

“Sire, only the deer in your pleasure garden will have immunity. What about all the other deer?”

“I spare their lives, too, my lord.”

“Sire, the deer will then be safe, but what about the rest of four-footed creatures?”

“I spare their lives too, my lord.”

“Sire, four-footed creatures will then be safe, but what about the flocks of birds”

“They will also be spared, my lord.”

“Sire, birds will then be safe, but what about the fish, those who live in the water?”

“I also spare their lives, my lord.”

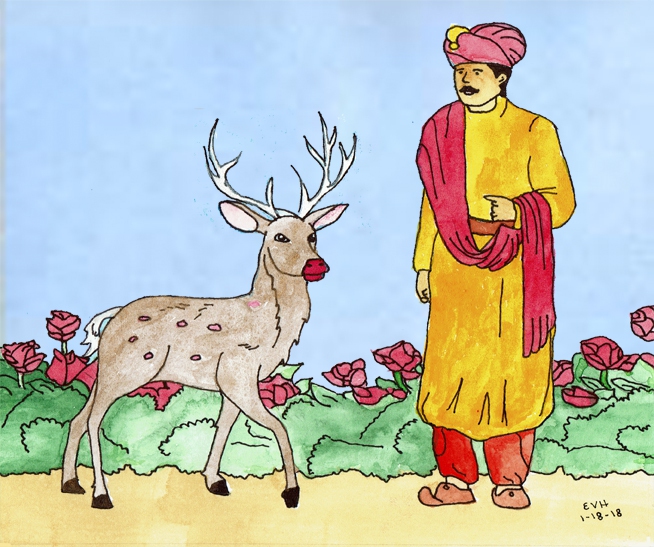

Figure: The King and Banyan Deer

Having interceded on behalf of all living creatures, the Bodhisatta arose, established the King in the Five Precepts and said, “Walk in righteousness, great King. Walk in righteousness and justice towards parents, children, townsmen, and country folk, so that when this earthly body is dissolved, you may enter the bliss of heaven.”

Thus, with the grace and charm that marks a Buddha, he taught the Dharma to the King. He stayed for a few days in the pleasure garden in order to instruct him, and then with his attendant herd he went into the forest again.

That doe gave birth to a fawn as fair as the opening bud of the lotus. He used to play about with the Branch deer. Seeing this his mother said to him, “My child, don’t go about with him, only go about with the herd of the Banyan deer.” And in order to persuade him, she repeated this stanza:

Keep only with the Banyan deer, and shun

The Branch deer’s herd; more welcome far

Is death, my child, in Banyan’s company,

Then even the most bountiful life with Branch.

Afterwards the deer, now enjoying immunity, used to eat men’s crops, and the men, remembering the immunity granted to them, did not dare to hit the deer or drive them away. So they assembled in the King’s courtyard and put the matter before him. He said, “When the Banyan deer won my favor, I promised him a boon. I would rather give up my kingdom than break my promise. Be gone! No one in my kingdom may harm the deer.”

But when Banyan heard about this, he called his herd together and said, “From now on you will not eat the crops of men.” And having done this, he sent a message to the men, saying, “From this day on, do not fence your fields, but merely mark the boundaries with leaves tied up around them.” And so, we hear, the custom began of tying up leaves to indicate the boundaries of the fields. And after that a deer was never known to trespass on a field marked in that way for they had been instructed by the Bodhisatta.

This is how the Bodhisatta ruled the deer of his herd, and this is how he acted all his life. At the end of a long life he passed away to fare according to his karma. The King too lived by the Bodhisatta’s teachings, and after a life spent in good works passed away to fare according to his karma.

At the close of this lesson, the Master repeated that, as now, in bygone days he had also been the salvation of the mother and her son. Then he preached the Four Noble Truths and showed the connection, linking the two stories he had told together. He identified the birth by saying, “Devadatta was the Branch deer of those days, and his followers were that deer’s herd. The nun was the doe, and Prince Kassapa was her son. Ānanda was the King, and I was King Banyan Deer.”