Jataka 72

Sīlavanāga Jātaka

The Ingrate

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

The theme of this story is gratitude, or the lack thereof.

The Buddha talked quite a lot about the importance of gratitude. In the Aṇguttara Nikāya, he said this:

“These two people are hard to find in the world. Which two? The one who is first to do a kindness, and the one who is grateful and thankful for a kindness done.” – [AN 2:118]

And in this passage the Buddha equates the quality of gratitude with integrity itself:

The Blessed One said, “Now what is the level of a person of no integrity? A person of no integrity is ungrateful and unthankful. This ingratitude, this lack of thankfulness, is advocated by rude people. It is entirely on the level of people of no integrity. A person of integrity is grateful and thankful. This gratitude, this thankfulness, is advocated by civil people. It is entirely on the level of people of integrity.” – [AN 2.31]

In the following story we see the great compassion of the Bodhisatta, who in this life is a resplendent elephant. We also see the old nemesis, Devadatta, who is such an ingrate that the forces of nature themselves are offended, and he is swallowed up into hell!

“Ingratitude lacks more.” This story was told by the Master while at the Bamboo Grove. It is about Devadatta. The monks sat in the Dharma Hall saying, “Sirs, Devadatta is an ingrate and does not recognize the virtues of the Blessed One.” Returning to the hall, the Master asked what topic they were discussing, and they told him. “This is not the first time, monks,” he said, “that Devadatta has proven to be an ingrate. He was just the same in bygone days also, and he has never known my virtues.” And so saying, at their request he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta was conceived by an elephant in the Himalayas. When he was born, he was white all over like a mighty mass of silver. His eyes were like diamond balls, like a manifestation of the five brightnesses. His mouth was red like scarlet cloth. His trunk was like silver flecked with red gold, and his four feet were as if polished with lacquer. Thus he was of consummate beauty, adorned with the ten perfections.

When he grew up, all the elephants of the Himalayas followed him as their leader. While he was living in the Himalayas with a following of 80,000 elephants, he became aware that an act of evil had occurred in the herd. So, detaching himself from the rest, he went to live in solitude in the forest, and the goodness of his life won him the name of Good King Elephant.

Now a forester of Benares came to the Himalayas and made his way into that forest to practice his craft. Losing his bearings and his way, he roamed to and fro. He stretched out his arms in despair and cried with the fear of death before his eyes. Hearing the man’s cries, the Bodhisatta was moved with compassion and resolved to help him in his need. So he approached the man. But at the sight of an elephant, the forester ran off in great terror. (Elephants who lived alone were considered dangerous.) Seeing him run away, the Bodhisatta stood still, and this brought the man to a standstill as well. Then the Bodhisatta again advanced, and again the forester ran away. Once again the Bodhisatta halted, and likewise, once more the forester halted. Seeing that the elephant stood still when he ran and only advanced when he himself was standing still, he concluded that the creature did not mean to hurt him, only to help him. So he courageously stood his ground this time. And the Bodhisatta drew near and said, “Why, friend man, are you wandering about here lamenting?”

“My lord,” the forester replied, “I have lost my bearings and my way, and I am afraid that I will die.”

Then the elephant took the man back to his home. There he entertained him for some days, regaling him with fruits of every kind. Then, saying, “Fear not, friend man, I will bring you back to the haunts of men,” the elephant seated the forester on his back and brought him to where men lived. But the ingrate thought to himself that he should remember where the elephant lived. So, as he travelled along on the elephant’s back, he noted the landmarks of tree and hill. At last the elephant brought him out of the forest and set him down on the high road to Benares, saying, “There lies your road, friend man. Tell no one, whether you are questioned or not, where I live.” And with that, the Bodhisatta made his way back to his own home.

Arriving at Benares, the man came - in the course of his walks through the city - to the ivory workers’ bazaar. There he saw ivory being worked into various forms and shapes. He asked the craftsmen what they would pay for the tusk of a living elephant.

“What makes you ask such a question?” they replied. “A living elephant’s tusk is worth a great deal more than a dead one’s.”

“Oh, then, I'll bring you some ivory,” he said, and off he went to the Bodhisatta’s dwelling. He took with him provisions for the journey and a sharp saw. Being asked what had brought him back, he whined that he was in so sorry and wretched a state that he could not make a living. So he had come to ask for a bit of the kind elephant’s tusk to sell for a living. “Certainly, I will give you a whole tusk,” the Bodhisatta said. “If you have a saw to cut it off with.”

“Oh, I brought a saw with me, sir.”

“Then saw my tusks off, and take them away with you,” the Bodhisatta said. And he crouched down on his knees on the earth like an ox. Then the forester sawed off a large portion of the Bodhisatta’s tusks! When they were off, the Bodhisatta took them in his trunk and said to the man, “Do not think, friend man, that it is because I do not value or prize these tusks that I give them to you. But a thousand times, a hundred thousand times, dearer to me are the tusks of compassion and the wisdom that can comprehend all things. And therefore, may my gift of these to you bring me wisdom.” With these words, he gave the pair of tusks to the forester as the price of wisdom.

And the man took them and sold them. And when he had spent the money, he went back to the Bodhisatta, saying that the two tusks had only brought him enough to pay his old debts, and he begged for the rest of the Bodhisatta’s ivory. The Bodhisatta consented, and gave up the rest of his ivory after having it cut off as before. And the forester went away and sold this also. Returning again, he said, “It's no use, my lord. I can't make a living anyhow. So give me the stumps of your tusks.”

“So be it,” the Bodhisatta answered, and he lay down as before. Then that vile wretch, trampling upon the trunk of the Bodhisatta, that sacred trunk that was like corded silver, and clambering upon the future Buddha’s temples which were as white as the snowy crest of Mount Kelāsa, kicked at the roots of the tusks until he had cleared the flesh away. Then he sawed out the stumps and went on his way. But scarcely had the wretch passed out of the sight of the Bodhisatta, when the solid earth, inconceivable in its vast extent, earth that can support the mighty weight of Mount Sineru and its encircling peaks, with all the world’s unsavory filth and excrement, now burst apart in a yawning chasm, as though unable to bear the burden of all that wickedness!

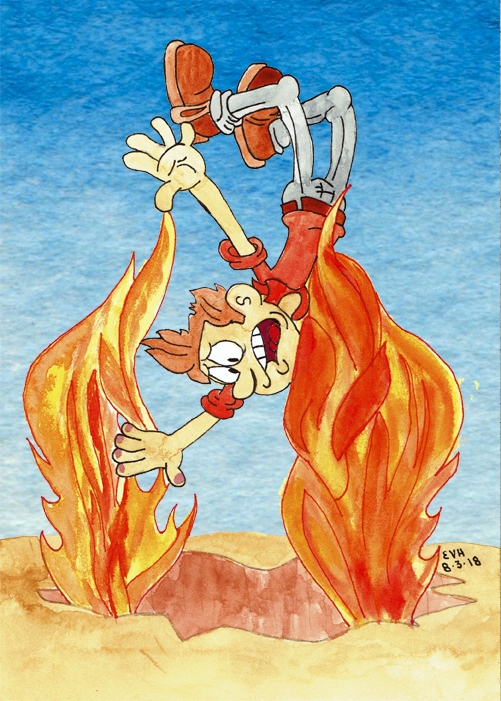

Figure: Even Hell is Offended by an Ingrate!

And straightway flames from the lowest Hell enveloped the ingrate, wrapping around him in a shroud of doom, and they took him away. And as the wretch was swallowed up in the bowels of the earth, the tree fairy that lived in that forest made the region echo with these words, “Not even the gift of worldwide empire can satisfy the thankless and ungrateful!” And in the following stanza the fairy taught the Dharma:

Ingratitude lacks more, the more it gets.

Not all the world can satisfy its appetite.

With such teachings the tree fairy made that forest re-echo. As for the Bodhisatta, he lived out his life, passing away at last to fare according to his karma.

The Master said, “This is not the first time, monks, that Devadatta has proved an ingrate. He was the same in the past also.” His lesson ended, he identified the birth by saying, “Devadatta was the ungrateful man of those days, Sāriputta was the tree fairy, and I was the Good King Elephant.”