Jataka 73

Saccaṃkira Jātaka

The True Parrot

as told by Eric Van Horn

originally translated by Robert Chalmers, B.A., of Oriel College, Oxford University

originally edited by Professor Edward Byles Cowell, Cambridge University

Oh, dear. Once again we see Devadatta fed to the literary wolves.

This story has a number of interesting characters. There is the Bodhisatta, as usual, who is a hermit at the beginning. Then there is Prince Wicked (great name, huh?) who - of course - has to be Devadatta.

We also meet a rat and a snake, both of whom had been very wealthy in their previous lives. But because they were stingy, they were reborn as lowly animals. However, to their credit, they undergo a personal transformation.

Then there is a lovely parrot. He is kind from beginning to end.

“They knew the world.” This story was told by the Master while at the Bamboo Grove. It is about killing. Seated in the Dharma Hall, the monks were talking about Devadatta’s wickedness, saying, “Sirs, Devadatta does not comprehend the Master’s excellence. He actually tries to kill him!” Then the Master entered the Hall and asked what they were discussing. Being told, he said, “This is not the first time, monks, that Devadatta has tried to kill me. He did the same thing in bygone days as well.” And so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once upon a time Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares. He had a son named Prince Wicked. He was fierce and cruel like a wounded snake. He spoke to nobody without abuse or striking them. The prince was like sand in the eye to everyone inside and outside the palace. He was like a ferocious ogre, so dreaded and savage was he.

One day, wishing to amuse himself in the river, he went to the water with a large entourage. A great storm formed, and utter darkness set in. “Hi there!” he cried to his servants. “Take me into the middle of the stream, bathe me there, and then bring me back again.” So they took him into midstream and there they discussed their situation, saying, “What will the King do to us? Let us kill this wicked wretch here and now! So in you go, you pest!” they cried as they flung him into the water.

When they made their way ashore, they were asked where the prince was. They replied, “We don’t see him. With the storm brewing, he must have come out of the river and gone home ahead of us.”

The courtiers went to the King, and he asked where his son was. “We do not know, sire.” they said. “A storm came on, and we left thinking that he must have gone on ahead.” At once the King had the gates thrown open. He went down to the riverside and searched diligently for the missing prince. But no trace of him could be found. For in the darkness of the storm, he had been swept away by the current. Coming across a tree trunk, he had climbed on to it and floated down stream, crying loudly from his fear of drowning.

Now there had been a rich merchant living in those days at Benares. He died, leaving 400 million rupees buried in the banks of that same river. And because of his craving for riches, he was reborn as a snake in the same spot as his dear treasure. Also in the same spot, another man had hidden 300 million rupees. And because of his craving for riches, he was reborn as a rat at that same spot.

The water rushed into their dwelling place. The two creatures escaped through the same route the water rushed in. They were making their way across the stream when they came upon the tree trunk to which the prince was clinging. The snake climbed up on one end and the rat on the other, and so both of them ended up on the trunk with the prince.

There was a silk cotton tree that grew on the bank of the river. There was a young parrot who lived there. This tree was uprooted by the swollen waters, and it fell into the river. The heavy rain beat down the parrot when it tried to fly, and it landed on this same tree trunk. And so there were now these four floating down stream together on the tree.

Now the Bodhisatta had been reborn in those days as a brahmin in the northwest country. Renouncing the world for the life of a recluse on reaching manhood, he had built a hermitage for himself at a bend in the river, and he was now living there. As he was pacing back and forth at midnight, he heard the loud cries of the prince. He thought to himself, “This fellow creature must not perish before the eyes of a merciful and compassionate hermit like me. I will rescue him from the water and save his life.”

So he shouted cheerily, “Do not be afraid! Do not be afraid!” He plunged into stream, seized hold of the tree by one end, and - being as strong as an elephant - pulled it back to the bank with one long pull. Then he set the prince safe and sound on the shore.

Then becoming aware of the snake and the rat and the parrot, he carried them to his hermitage as well. He lit a fire, and he warmed the animals first because they were weaker. Then he warmed the prince. This done, he brought fruits of various kinds and gave them to his guests, looking after the animals first and the prince afterwards. This enraged the young prince who said to himself, “This rascally hermit pays no respect to my royal birth, but actually gives brute beasts more importance than me.” And he formed a great hatred against the Bodhisatta!

A few days later, when all four had recovered their strength and the waters had subsided, the snake said goodbye to the hermit with these words, “Father, you have done me a great service. I am not poor, for I have 400 million rupees of gold hidden at a certain spot. If you ever want money, all of it will be yours. You only have to come to the spot and call ‘Snake.’”

Next the rat said goodbye with a similar promise to the hermit as to his treasure, telling the hermit to come and call out “Rat.” Then the parrot said goodbye, saying, “Father, I do not have any silver or gold, but if you ever want choice rice, come to where I live and call out ‘Parrot.’ And with the help of my family, I will give you many wagon-loads of rice.”

Last came the prince. His heart was filled with shameful ingratitude and with a determination to put his benefactor to death if the Bodhisatta should come to visit him. But, concealing his intent, he said, “Come to me, father, when I am King, and I will give you the Four Requisites.” (food, shelter, medicine, clothing) So saying, he left, and not long after he succeeded to the throne.

The Bodhisatta decided to put their declarations to the test. First he went to the snake. Standing by its home, called out “Snake.” At the word the snake darted forth, and with every mark of respect he said, “Father, in this place there are 400 million rupees in gold. Dig them up and take them all.”

“It is well,” the Bodhisatta said. “When I need them, I will not forget.”

Then saying goodbye to the snake, he went to where the rat lived and called out “Rat.” And the rat did as the snake had done. Going next to the parrot and calling out “Parrot,” the bird flew down at once from the tree top. He respectfully asked whether it was the Bodhisatta’s wish that he and his family should gather rice for the Bodhisatta from the region round the Himalayas. The Bodhisatta dismissed the parrot also with a promise that, if needed, he would not forget the bird’s offer.

Last of all, in order to test the King, the Bodhisatta went to the royal pleasure garden. On the day after his arrival, he made his way, carefully dressed, into the city on his alms round. Just at that moment, the ungrateful King, seated in all his royal splendor on his elephant of state, was passing in a solemn procession around the city followed by a vast entourage. Seeing the Bodhisatta from afar, he thought to himself, “Here’s that rascally hermit come to house himself and burden me with his appetite. I will cut his head off before he can tell the world the service he rendered me.”

With this intent, he signaled to his attendants. When they asked what he wanted, he said, “I think that rascally hermit is here to beg from me. See that the pest does not come near me. Seize and bind him. Beat him at every street corner, then march him out of the city, chop off his head at the place of execution, and impale his body on a stake.”

Obedient to their King’s command, the attendants put the innocent Great Being in bonds and beat him at every street corner on the way to the place of execution. But all their beatings failed to move the Bodhisatta or to wring from him a single cry of “Oh, my mother and father!” All he did was to repeat this stanza:

They knew the world, who framed this true proverb —

“A log repays a kindness better than some men.”

He repeated these lines wherever he was beaten, until at last the wise among the bystanders asked the hermit what service he had rendered to their King. Then the Bodhisatta told the whole story, ending with the words, “So it comes to pass that by rescuing him from the torrent I brought all this woe upon myself. And when I think how I have left unheeded the words of the wise of old, I exclaim the verses you have heard.”

Filled with indignation, the nobles and brahmins and all classes cried out with one accord, “This ungrateful King does not recognize even the virtue of this good man who saved his majesty’s life. How can we gain any benefit from this King? Seize the tyrant!” And in their anger, they rushed upon the King from every side and killed him right then and there as he rode on his elephant. They pelted him with arrows and javelins and stones and clubs and any weapons that came to hand. They dragged the corpse by the heels to a ditch and threw it in. Then they anointed the Bodhisatta King and set him to rule over them.

As he was ruling in righteousness, one day he decided to once again try the snake and the rat and the parrot. Followed by a large entourage, he went to where the snake lived. At the call of “Snake,” out came the snake from his hole. With every mark of respect he said, “Here, my lord, is your treasure. Take it.” Then the King delivered the 400 million rupees of gold to his attendants.

Proceeding to where the rat lived, he called, “Rat.” Out came the rat. He saluted the King and gave his 300 million rupees. He placed this treasure in the hands of his attendants as well. Then the King went to where the parrot lived and called “Parrot.” And in the same way the bird came. Bowing down at the King’s feet, he asked whether he should collect rice for his majesty. “We will not trouble you,” the King said, "until rice is needed. Now let us be going.”

So with the 700 million rupees of gold, and with the rat, the snake, and the parrot as well, the King journeyed back to the city. Here, in a noble palace, he had the treasure stored and guarded. He had a golden tube made for the snake to live in, a crystal casket to house the rat, and a cage of gold for the parrot. Every day by the King’s command food was served to the three creatures in vessels of gold: sweet parched corn for the parrot and snake, and scented rice for the rat. And the King abounded in charity and all good works. Thus in harmony and goodwill with one another, these four lived their lives, and when their end came, they passed away to fare according to their karma.

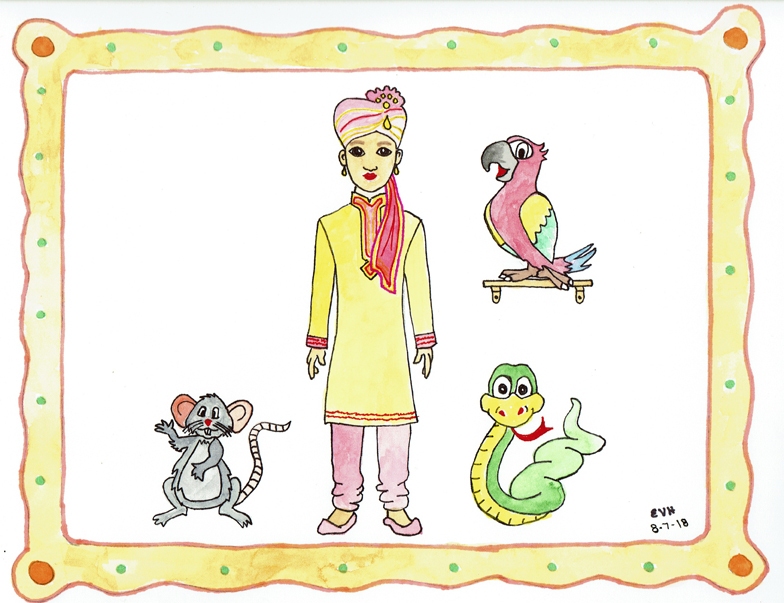

Figure: Family Portrait

The Master said, “This is not the first time, monks, that Devadatta has tried to kill me. He did this in the past also.” His lesson ended, he showed the connection and identified the birth by saying, “Devadatta was King Wicked in those days, Sāriputta the snake, Moggallāna the rat, Ānanda the parrot, and I was the righteous King who won a kingdom.”

(Sāriputta and Moggallāna were the Buddha’s two chief disciples, and Ānanda was his attendant.)